On both of my recent research trips to Rio de Janeiro I stayed on Machado de Assis Street, in the neighborhood of Flamengo. Every Tuesday, the sounds of vendors setting up their stalls in front of my window for the weekly fruit and vegetable market would wake me up at 6 am. After lengthy and unsuccessful attempts to go back to sleep, I would reluctantly get up and go out for a morning stroll in the market, already crowded by this hour. Machado de Assis never lived in the street now bearing his name (though he did live close by for several years, on Catete street), but I still imagined him having his cafezinho at the corner, observing the bustling commercial activity of a traditional market in a fast-growing, urban metropolis, and considering his next work. Reading Ex Cathedra, a new translation of some twenty-one short stories written by Machado, was a great opportunity not only to discover lesser-known works of the great Brazilian author, but also to recall that repeated annoying, yet joyful morning experience.

On both of my recent research trips to Rio de Janeiro I stayed on Machado de Assis Street, in the neighborhood of Flamengo. Every Tuesday, the sounds of vendors setting up their stalls in front of my window for the weekly fruit and vegetable market would wake me up at 6 am. After lengthy and unsuccessful attempts to go back to sleep, I would reluctantly get up and go out for a morning stroll in the market, already crowded by this hour. Machado de Assis never lived in the street now bearing his name (though he did live close by for several years, on Catete street), but I still imagined him having his cafezinho at the corner, observing the bustling commercial activity of a traditional market in a fast-growing, urban metropolis, and considering his next work. Reading Ex Cathedra, a new translation of some twenty-one short stories written by Machado, was a great opportunity not only to discover lesser-known works of the great Brazilian author, but also to recall that repeated annoying, yet joyful morning experience.

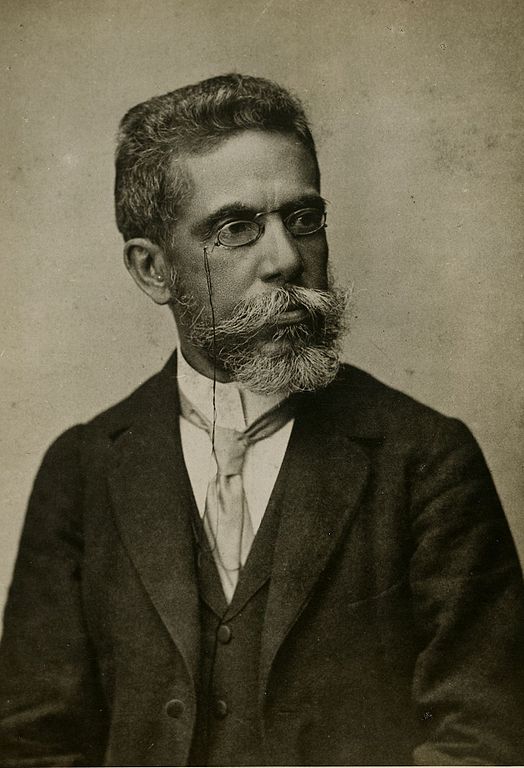

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis was born in 1839 to a son of freed slaves who worked as a house painter and a Portuguese washerwoman from the Azores who died before he turned 13. He was raised by a stepmother who worked as a maid. Despite his unprivileged social and racial background—slavery was legal in Brazil until 1888—Machado managed to break from hierarchical determinism. Already as a teenager he was a keen learner. A local priest taught him Latin; a baker introduced French, and he later taught himself other modern and ancient languages. As a typographer’s apprentice, Machado studied the printing business and, later working as a proofreader and salesman at a bookstore, he was able not only to read the classics but also to meet some of Rio de Janeiro’s eminent authors. Although he never left Rio, Machado’s cultural and literary understanding was deeply rooted in world literature and the intellectual discourse of the period.

His first successful poems and short stories appeared in periodicals and illustrated magazines aimed at Rio’s rising middle class, attracting young socialites (particularly women) with themes of sexual desire and leisure time. Yet if this first phase of writing was romantic and humorous, Machado’s later works were pessimistic, melancholic, and disillusioned, presenting a much more cynical view of Brazilian society. Some critics highlight the physical and psychological breakdown Machado suffered in 1878—developing epilepsy and a speech disorder as well as confronting his deprived socio-racial position—to explain the shift in the author’s literary production. Others reject this interpretation, pointing to continuity in the developments of his literary technique and aesthetics.

Whatever the cause, after 1880 Machado’s works portray a somber look at society, dealing with death, insanity, gossip, hypocrisy, greed, and anxiety. The most well known is Epitaph of a Small Winner (Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas, 1880), a fictional autobiography of a dead hero, telling his life story from his grave. These works also brought fame. Critics praised Machado work and the Emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro II, awarded him the Order of the Rose. In 1896, Machado was a founding member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters, serving as its first president until his death in 1908.

The twenty-one stories collected in Ex Cathedra—all originally published after 1880—beautifully represent this later phase. They take us on a journey to late nineteenth-century Brazil, mixing the mundane with the unique and sometimes hallucinatory human experience, as rightfully pointed out in the introduction. In one story, we follow a man’s relentless but unsuccessful attempts to get a loan for his entrepreneurial fantasies. In another, we witness the anxieties of an adoptive father afraid to lose his adolescent daughter when she marries. We find ourselves listening to a delirious dialogue between a member of Rio’s elite and a historic figure from ancient Greece about fashion and modernity. Or we observe the well-crafted plan of an elderly avid reader to make his goddaughter and niece fall in love.

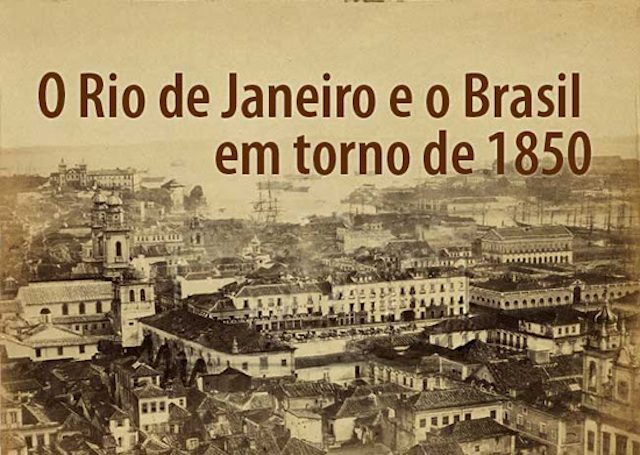

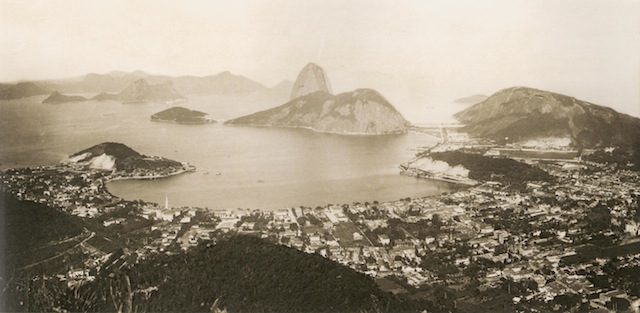

Machado’s vignettes, with their mix of the everyday and the surreal, also shed historical light on the transitions Brazilians underwent at the turn of the century and their attempts to deal with those rapid changes. When Machado de Assis was born, Brazil was a rather stable monarchical empire, slavery was legal, and the economy was based mainly on agriculture exports such as sugar and cacao. When publishing the stories gathered in Ex Cathedra, however, both the empire and slavery system were on the verge of collapse or already gone: slavery was abolished in 1888 and monarchy in 1889. Thousands of newly constructed railroad lines introduced the first signs of industrial development and government-organized European immigration aimed to expand the labor force, whiten population, and “modernized” society. The dialogues and arguments among Machado’s characters testify to these shifts, and the author makes an effort to ridicule the difficulties of adjusting to modern developments, expressing the characters’, and perhaps his fear of the uncertain future of the new republic and its promise of “order and progress.”

Images documenting historical change in nineteenth century Rio:

Ex Cathedra is an important addition to Machado de Assis’s corpus of English translations. It brings together stories published during the author’s most productive and mature period (1880-1906), some of them appearing for the first time in English. The translations are uneven at times and some stories would have benefitted from better editing. Translating Machado de Assis, however, is not an easy job. Characters frequently use both formal and common registers, and the tone can quickly shift from playful to serious. As this is a bilingual edition, scholars can compare the original with the translation. Yet this collection is certainly not only for the bilingual researcher. English speakers will enjoy the captivating stories, and will find a brief glossary at the end to clarify Portuguese words used in translated text.

Ex Cathedra: Stories by Machado de Assis: Bilingual Edition, edited by Glenn Alan Cheney, Luciana Tanure, Rachel Kopit (New London Librarium, 2014)

Translations by: Laura Cade Brown, Krista Brune, Glenn Alan Cheney David George, Linda Ledford-Miller, Ana Lessa-Schmidt, Nelson López Rojas, John Maddox, Adam Morris, Rex P. Nielson, Leila Osman, Marissel Hernández Romero, Steven K. Smith, Lisandra Sousa, Luciana Tanure, Nelson Vieira

You may also like:

Seth Garfield on his book In search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States and the nature of a Region

Elizabeth O’Brien on labor history in the sugar industry in Brazil

Eyal Weinberg on labor history in Sao Paulo

Darcy Rendón on the social history of the lottery in Brazil