“It was the whiteness of the whale that above all things appalled me. But how can I hope to

explain myself here; and yet, in some dim, random way, explain myself I must,

else all these chapters might be naught.”[1]

These few words show how difficult it was for Herman Melville, in his novel Moby Dick, to write from nature’s perspective in the 19th century. In the last decades, with the global climate change emergency in the background and enormous progress in scientific fields, this literary connection has been explored from a broader humanistic perspective. But most importantly, it can also be examined from a historical point of view, using the history of science, history of technology, and environmental history to understand extreme natural landscapes –in Antarctica, for example, or in Finland or Canada– and their relationship with extractivist, nation-state, and scientific knowledge. At the intersection of these diverse fields and research agendas can be situated the first book of the writer and environmental historian Bathsheba Demuth, Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait.

When Demuth was 18, she moved to an indigenous village in the Canadian Arctic and planned to stay there for 3 to 4 months. But instead, she ended up spending years training huskies for sled dogs. As she mentions in one of her interviews, to help to survive in this harsh and cold environment, her host family encouraged her to pay attention to the nonhuman world and how to imagine her actions from the perspective of the animals and natural spaces, such as the tundra, the ocean and the wind. As she remarks, this changed her perception and created two main questions for her research: “How do your ideas change nature?” and “How does nature change the way that we think about the world?”[2]. She recognizes that she wrote her book with these two questions in her mind.

Floating Coast, as Demuth defines it, is the history of the Russian and American sides of the Bering Strait, where Alaska and Siberia almost encounter one another. More specifically, it examines the historical evolution of ideas about landscapes over the course of 200 years. The ideas in question come from indigenous communities, including the Yupik and Chukchi in Russia and the Iñupiat and Yupik in Alaska, as well as from U. S. capitalism and Soviet communism. Demuth also describes extreme natural landscapes from the perspective of whales and foxes in addition to examining the viewpoints of many kinds of people. She defined her studies as a “historical guide to ways that we can imagine our relationships with environment in the present.”[3] Between 2020 to 2021, Floating Coast received numerous awards from the American Historical Association, the American Society for Environmental History, and the Western Historical Association. It also received several non-fiction literary awards due to its beautifully written narrative construction of time and historical space.

Demuth divides her book into five parts– “Sea,” “Shore,” “Land,” “Underground,” and “Ocean”–with two chapters each and one Epilogue. To write these ten chapters, she used three different types of primary sources. The first comprises oral history from indigenous communities, collected using ethnographic methods and from state records. The second, used to follow state ambitions, is composed of local, regional, and national records from Imperial Russia, the United States, and the Soviet Union. Finally, Demuth also used individual memoirs and scientific materials. Floating Coast analyzes these sources using techniques developed by a range of fields, including environmental and transnational history.

Demuth showcases two of environmental history’s most significant methodological contributions. First, Floating Coast uncouples its analysis from traditional understandings of time and from nation-state structures to focus on places and the historical interactions between the human and non-human world. Across the landscapes of “Sea,” “Shore,” “Land,” “Underground,” and “Ocean,” Demuth invites us to rethink the classic notions of linear time and economic progress. In such extreme spaces as Beringia, environmental historians (and different scholars) need to write about time in a way that isn’t always strictly chronological. In Floating Coast, the conception of time comes from places, animals, and seasons.

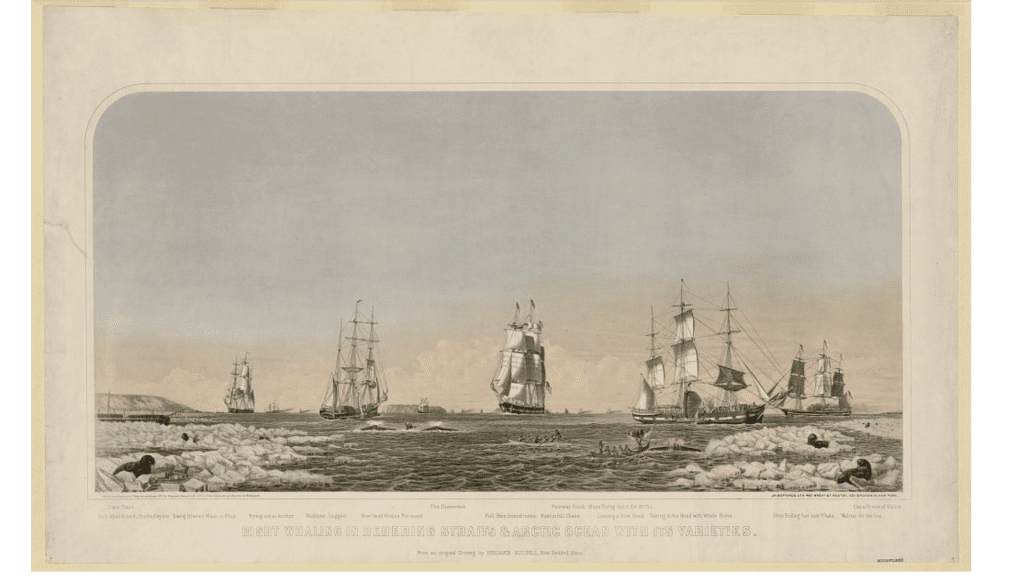

Second, this chronological approach constantly flows through a historical narrative because it follows material and imaginaries of energy. Demuth’s book shows how an ecological space becomes a source of commodities through the hunting of whales, bison, and walruses, as well as through gold extraction. Demuth explains how an imperial view of extreme landscapes and natural resources developed in the United States, Imperial Russia, and the Soviet Union. She concludes that capitalism and socialism are similar insofar as they both look for commodities in landscapes. The Indigenous narratives Demuth explores present a very different perspective. “History life in Beringia,” she explains, “was shaped partly by the ways energy moved over the land through the sea.”[4] This concept of energy, especially energy transition, is behind every chapter. Demuth describes energy moving, “from sea to coast, coast to land, land underground and finally back to the ocean.”[5] For example, her book shows how whales turn into light.

To conclude, Demuth immerses us in a world extreme natural scenery and creates an atmosphere especially well-suited to talking about nature, desolation, and frozen areas. It is a beautifully written book that presents an incisive analysis of primary and secondary sources. It also invites historians from different fields to read and rethink the way history is written, showcasing the methodological and theoretical options environmental history offers. Demuth’s decision to write about time from a nature perspective is especially provocative and worthy of note.

Yohad Zacarías is a doctoral student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. She holds a B.A. and M.A. in History from Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (Chile). As a Fulbright doctoral fellow, her current research interests focus on electrification’s urban, environmental, and technological impact in Chile and Latin America between the 19th and 20th centuries. In addition, she has received scholarships from the Latin American and Caribbean Society of Environmental History (SOLCHA) at Stanford University (CLAS) and the Erasmus Program at the University of Copenhagen. Before graduate school, Yohad worked as an Outbound International Mobility Coordinator in the International Relations Office at Universidad de Chile.

[1] Herman, Melville. Moby Dick: or the Whale. Minneapolis: First Avenue Editions, 2014, 232.

[2] Bathsheba Demuth, “Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait,” YouTube, WW Norton, August 1, 2019, https://youtu.be/K4G42JyunzY, accessed December 01, 2022.

[3] Bathsheba Demuth, “Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait,” YouTube, WW Norton, August 1, 2019, https://youtu.be/K4G42JyunzY, accessed December 01, 2022.

[4] Bathsheba Demuth, Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019, 4.

[5] Demuth, Floating Coast, 5.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.