Housed in a miscellaneous folder in the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection is an assortment of thirteen broadsides, letters, newspapers, and drafts of two articles by prominent Texas historian Herbert Gambrell (1898-1982). Gambrell had a long and prestigious academic career studying Texas history as a fixture at Southern Methodist University. These documents all originate from a summer research trip to Mexico City, where, in 1925, Gambrell studied the creation of a new, factional, schismatic Mexican Church, the Apostolic Mexican Catholic Church (known by its Spanish acronym, ICAM), in order to better understand the causes and impacts of the budding movement. These papers give us a particularly interesting view into Mexican cultural life in the 1920s through the lens of Church relations and offer understanding of state-sponsored anticlericalism during this period.

In February 1925, one hundred men took over the Catholic Church of La Soledad in Mexico City, removed the head priest of the church, and announced that they were converting it into the Apostolic Mexican Catholic Church (ICAM). An ex-clergyman by the name of Joaquín Pérez then entered and announced he was the “Patriarch” of this new Church. Breaking off from the Roman Catholic Church, the ICAM pledged allegiance to the Mexican state instead of recognizing the Papacy in Rome as the spiritual head of the church. Picking and choosing which Catholic dogmas, or fundamental tenants of the faith, to keep, this new church allowed priests to marry, offered mass in Spanish, instead of Latin, left biblical interpretation to the individual, and did not require members to pay tithes, or financial contributions to the church. ICAM took root in several hundred communities in the southern and central states of Mexico and, in some places, lasted until the 1940.

This incident occurred in the context of renewed anticlericalism and persecution in Mexico and it contributed to the start of the Cristero Rebellion, when from 1926 to 1929, Catholic peasants took up arms against the state in order to restore the place of the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico. The Mexican president, Plutarco Elias Calles (1924-1928), a Protestant and fervent anti-clerical, blessed this schismatic Mexican Church and allowed it to function freely during his presidency. Its creation represented one challenge of many during this time to the position of the Roman Catholic in Mexico.

Herbert Gambrell arrived in Mexico City only six months after the birth of this schismatic church. The drafts of his articles come from interviews with the head of the ICAM, Joaquín Pérez, and Mexican Secretary of the Chamber and Government, López Sierra. Also included in this folder are newspaper clippings relating to the ICAM, a reprint of the ICAM’s main ideology, called Bases fundamentals, a personal letter, and a short letter from López Sierra asking him to share the findings from his articles.

Trying to contextualize the creation of the new church, Gambrell starts out by commenting that this is not the first effort to lead Mexicans away from the Catholic Church in Rome, but this is one of the most successful examples. The ICAM arose from a long nationalistic tradition in Mexico, as the church’s slogan, “Mexico for Mexicans,” suggests. Nevertheless, the church remained controversial in Mexico. Gambrell notes that there were pamphlets plastered all around the city reading “Viva el papa!” (Long live the Pope) alongside those proclaiming “Muera el papa! Viva Mexico,” (Death to the Pope, Long Live Mexico) suggesting the controversy remained unresolved.

Gambrell’s observations about the creation of the ICAM emphasize the disjointed implementation of certain segments of the Mexican Constitution. After the Mexican Revolution of 1910, the Constitution of 1917 was written with a liberal, secularist, political view: various articles limited the power of the Catholic Church within Mexico in an effort to strengthen the government. Because Article 130 of the Constitution required the nationalization of all church property, Gambrell remarked that the ICAM ran into obstacles because their private Churches were not publicly owned “templos.” Another 1917 article required foreign-born priests to be removed from their positions in the Catholic Church, many of whom were replaced by Mexicans. The ICAM’s nationalist message was less powerful now that the Catholic Church was less “foreign.”

The budding evangelical church was not without faults, according to Gambrell. He comments on one of the major faults of the movement, namely the absence of proper leadership. The ICAM was also more political than spiritual: “It is semi-political in its makeup . . . a religious movement which does not come from a deep spiritual ideal can succeed more or less apparently, but does not triumph in a definite way.” Gambrell concluded that the success of the new church would only show itself with time.

Gambrell’s insights provide a particularly fascinating perspective as he, himself, came from an evangelical family, growing up with a Baptist pastor. His opinions were formed through the lens of his own experiences as the son of a Baptist pastor. Gambrell believes that ICAM marked an important step towards what he considered real progress and celebrates that “Rome’s grip has been weakened, seriously weakened, by the movement, nor will she ever be able to regain what she has lost.” With documents written in both English and Spanish, this collection is an accessible resource for interrogating state anticlericalism and the 1917 Mexican constitution.

Herbert Gambrell Papers, “The New Catholic Church of Mexico,” Benson Latin American Collection, (all quotes come from this collection of documents).

David C. Bailey, Viva Cristo Rey, The Cristero Rebellion and the Church-State Conflict in

Mexico, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1974)![]()

You may also like:

For Greater Glory (2012), reviewed by Cristina Metz.

War Along the Border: The Mexican Revolution and the Tejano Communities edited by Arnoldo De León (2012), reviewed by Lizbeth Elizondo.

The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene (2003), reviewed by Matthew Butler.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

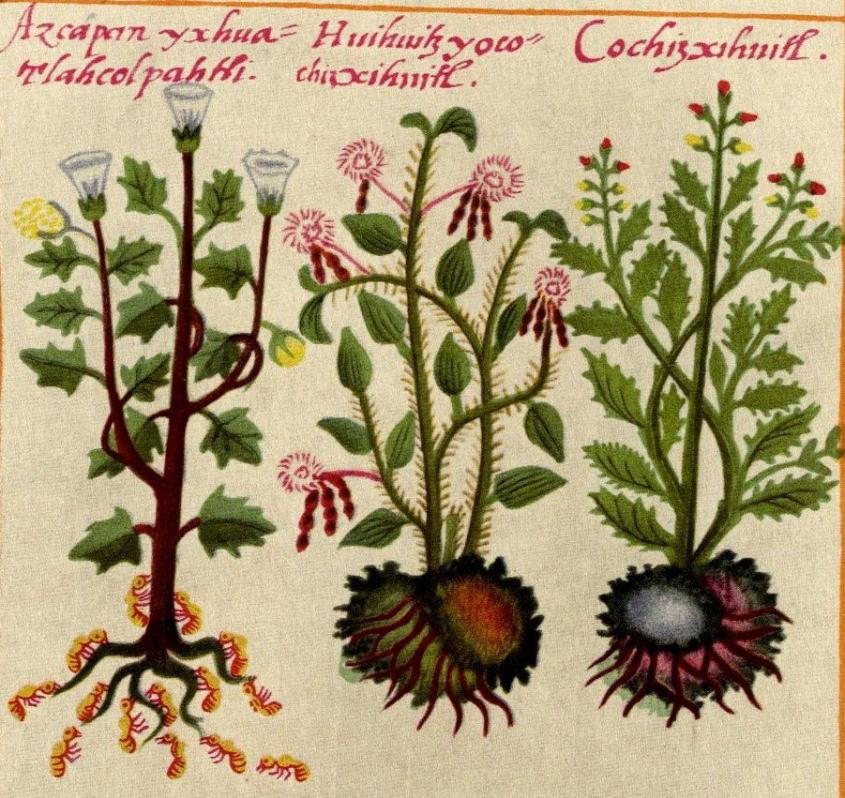

The Codice de la Cruz-Badiano is an example of the encounter of between writing systems, and thus of systems of knowledge, with multiple swings from the pictographic-glyphic tradition to the alphabetical. The illustrations are by no means subordinated to the writing. Visual evidence and linguistic analysis of Náhuatl offer ways of approaching the complexities of cultural forms and to provide information about natural history that was not present in the Latin texts.

The Codice de la Cruz-Badiano is an example of the encounter of between writing systems, and thus of systems of knowledge, with multiple swings from the pictographic-glyphic tradition to the alphabetical. The illustrations are by no means subordinated to the writing. Visual evidence and linguistic analysis of Náhuatl offer ways of approaching the complexities of cultural forms and to provide information about natural history that was not present in the Latin texts.