Reinventing Modern China: Imagination and Authenticity in Chinese Historical Writing (University of Hawai’i Press, 2013), by Huaiyin Li

Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations (Columbia University Press, 2014). by Zheng Wang

Will the Chinese economy continue to grow? Will Chinese politics democratize? Will the Chinese military try to dominate Asia? It is no wonder that we cannot agree on China’s future; we cannot even agree on its past. In fact, how to interpret the past is a heavily disputed subject in China, because history has always been a tool to promote one’s political agenda in the present. Huaiyin Li’s Reinventing Modern China and Zheng Wang’s Never Forget National Humiliation analyze the complex politics surrounding modern Chinese historiography.

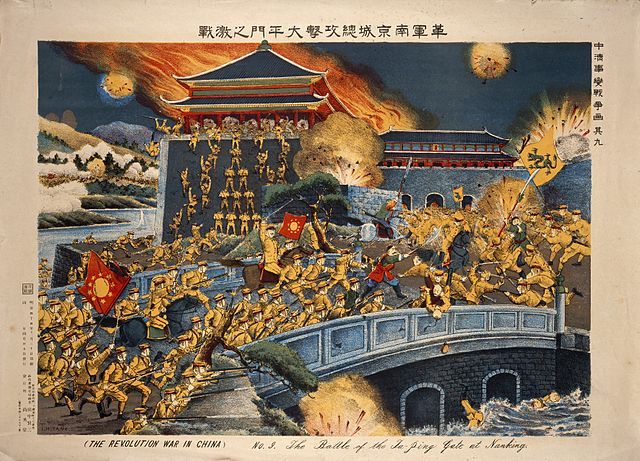

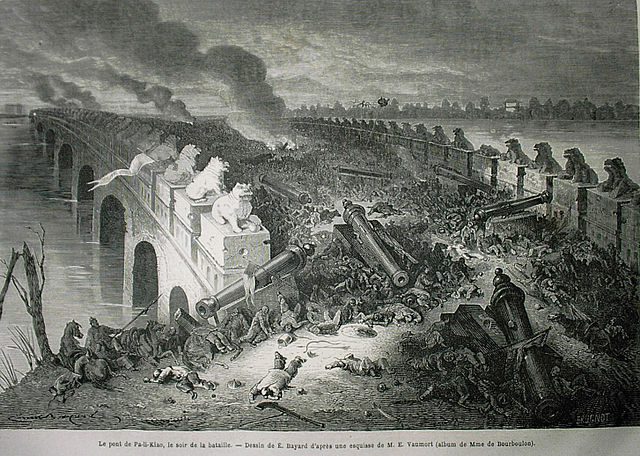

Li traces the development of historical narratives from the Republican era to the present. In the Republican era, western-educated intellectuals, such as Jiang Tingfu, blamed China’s turmoil, from the Opium War in 1860 to the 1911 Revolution, on its backwardness in order to support the Nationalist Party’s state-building efforts. In response, Communist historians, especially Fan Weilan, attributed Chinese suffering to the collusion of domestic traitors with foreign imperialists,, a de facto criticism of the Nationalists’ cooperation with the Western powers. Following the Communist victory in the civil war in 1949, Hu Sheng’s narrative, which put class struggle on the center of historical developments, prevailed, serving Mao Zedong’s land reform and collectivization campaigns. After further radicalization during the Great Leap Forward and the Great Cultural Revolution, the reform movements and market liberalization under Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s facilitated the revival of the pre-revolutionary historiography, which emphasized China’s century-long efforts for modernization, as the main trend of its modern history.

Wang discusses how history education in today’s China nurtures anti-Western nationalism among Chinese people, which in turn provides a grass-roots foundation for its uncompromising foreign policy. In response to the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989, which shattered Chinese hopes for democracy and tainted the legitimacy of communism, the Chinese government launched the Patriotic Education Campaign in 1991. Neglecting the modernization and state-building efforts of the Republican era, it created a singular collective memory that China had always been victimized by foreign powers for a hundred years until the communist revolution. With the slogan “Never Forget the National Humiliation,” the official historiography now champions the Communist Party as the guardian of Chinese security and the agent for “the rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation,” justifying its one-party rule in the post-Tiananmen era. The Patriotic Education Campaign affects not only Chinese classrooms but also popular culture, including radio, TV shows, and movies, spreading what Wang calls “the culture of insecurity” among Chinese people, as observed in their angry reactions to the U.S. bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999 and the Western criticism on China’s human right abuse in Tibet before the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

By examining how China sees its past, Li and Wang offer useful frameworks to think about its future. Li, for example, concludes his book with a bold suggestion to establish a new “master narrative” of modern Chinese history, which highlights China’s search for its own modernity, distinct from Western modernity. By doing so, he argues, Chinese history can finally escape politicization. Readers may wonder, however, whether too much emphasis on China’s own modernity can give rise to xenophobic nationalism, as Japan’s pursuit of its own modernity nurtured imperialism in the 1930s. Like Li, Wang also implicitly calls for a more balanced historical narrative, as the unbalanced historical education in today’s China has unfavorable impact on its foreign policy, but readers are left wondering how it is possible when the Patriotic Education Campaign sanctions the Communist authoritarianism. A similarly difficult question is: how would Chinese people deal with the trauma of the Tiananmen Massacre, if the historical narrative were to change at all?

Anthony D. Smith once wrote, “no memory, no identity; no identity, no nation.” Memories in the past, triumphant or traumatic, shape the nation at present. Li and Wang illuminate, albeit within differing disciplinary scopes, how this process works for modern Chinese history. Their books are both fascinating not only for historians and political scientists but also for anyone interested in the past and future of China.

You may also like

Zhaojin Zeng reviews Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State (2008), by Yasheng Huang

Huaiyin Li discusses Joseph Esherick’s history of a Chinese family through Chinese History

James Hudson on The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China (2009), by Jay Taylor

All images via Wikimedia Commons.