by Adrienne Morea

by Adrienne Morea

Harry Burgwyn was twenty-one years old when he led more than eight hundred soldiers of the 26th North Carolina Infantry into battle at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863. Two and a half days later, after two bloody assaults, fewer than one hundred remained fit for duty. According to some calculations, the 26th North Carolina “incurred the greatest casualties of any regiment at Gettysburg” (Gragg 210). Despite these losses, the 26th rebuilt itself and continued fighting for an additional twenty-one months.

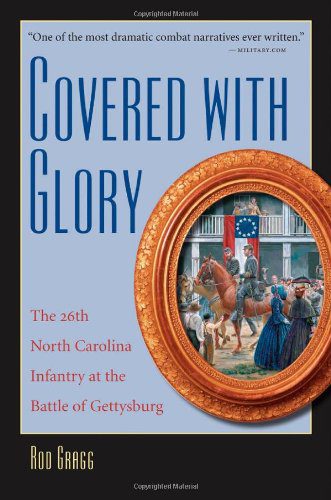

This fascinating regiment is the subject of Rod Gragg’s Covered with Glory: The 26th North Carolina Infantry at Gettysburg. As the subtitle indicates, the majority of the book covers the Gettysburg campaign, but it is also an admirable history of the 26th North Carolina and its role in the American Civil War, from the regiment’s establishment in the summer of 1861 to its surrender at Appomattox and the postwar lives of its survivors.

This book is the story of the men and their regiment. By and large, it is not about politics, nor is it an argument about the causes or broad issues of the war. It is a narrative of the experiences of men and boys, in camp, on the march, and on the battlefield. Such a detailed, personal view can enhance anyone’s understanding of the monumental history involved.

Readers make the acquaintance of many Tar Heels, from privates to generals, who fought in or were closely associated with the 26th North Carolina. This regiment was remarkable for the youthfulness of its commanders, several of whom were college students before the war. Colonel Henry King Burgwyn Jr. had graduated from two

institutions of higher education before he was twenty. Major John Thomas Jones, twenty-two, had been a schoolmate of Burgwyn. Lieutenant Colonel John Randolph Lane turned twenty-eight the day after the fighting at Gettysburg ended. At thirty-four, Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew, who commanded the brigade that included the 26th, was already an accomplished scholar in several disciplines. The officers are important and engaging characters, but they are not the entire story. Readers also meet lowlier fellows such as Private Jimmie Moore, a farmer’s son who was fifteen when he enlisted and seventeen when he was wounded at Gettysburg, and Julius Lineback, a slight, observant musician of twenty-eight.

Gragg tells the tale with eloquence, with great affection for the men of the 26th, and with respect for their opponents in blue. Covered with Glory is a work of nonfiction, but it is also a fine piece of storytelling. Sixteen pages of images help to put faces on the people in the text.

We are now in the sesquicentennial year of the Gettysburg campaign. This is a fitting time to study the events and people of the Civil War. As Lane said in a postwar speech, the story of the men of the 26th does not belong only to North Carolina or to the South, but rather it is “the common heritage of the American nation” and represents “the high-water mark of what Americans have done and can do” (Gragg 245). If you are interested in the American Civil War, in nineteenth-century life, or in military history, you should read this book. If you are or ever have been a college student in your twenties, you should read this book.

Photo credits:

Unidentified Union soldier, 1860-1870 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

And be sure to check out Kristopher Yingling’s winning submission to Not Even Past’s Spring Essay Contest.