Must must-read books on the Vietnam War

Christian Appy, American Reckoning: The Vietnam War and Our National Identity (2015).

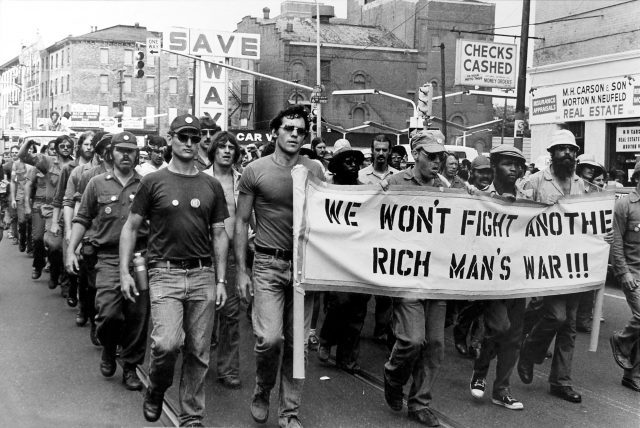

The latest in a long line of studies focused on the legacies of the war in the United States, Appy’s book covers everything from film and literature to foreign and military policy.

Pierre Asselin, Hanoi’s Road to the Vietnam War, 1954-1965 ( 2013).

Asselin’s book, rooted in extensive research in Vietnamese records, is one of the first to examine the North Vietnamese side of the decisions that led to a major war in 1965. Scholars will no doubt get better access to North Vietnamese materials in the years to come, but this book is an extraordinary accomplishment, shedding light on matters that have defied study for decades.

William J. Duiker, Ho Chi Minh: A Life (2000).

Duiker’s exceptionally engaging biography draws on material from around the world deftly analyzes the blend of nationalism and communism at the heart of Ho Chi Minh’s revolutionary activism.

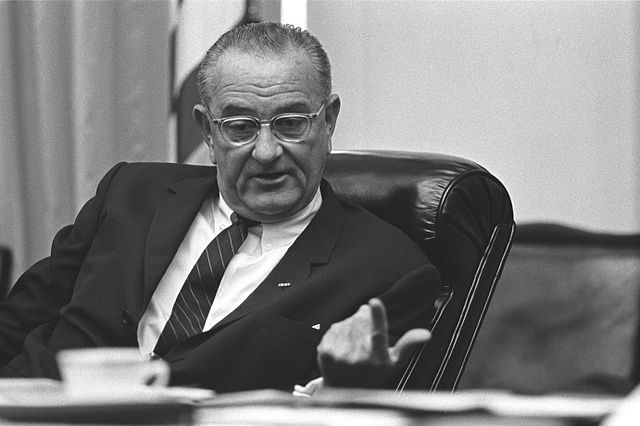

Fredrik Logevall, Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

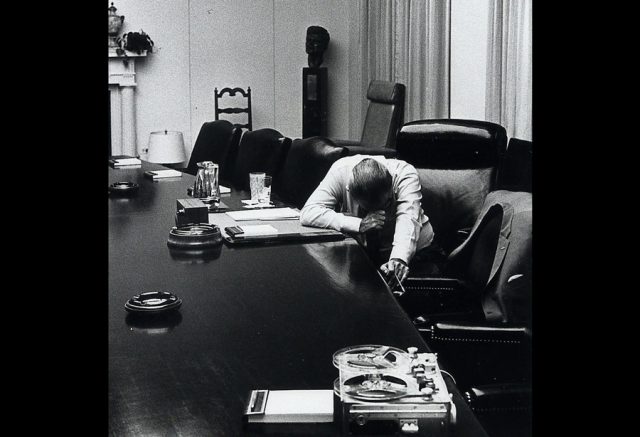

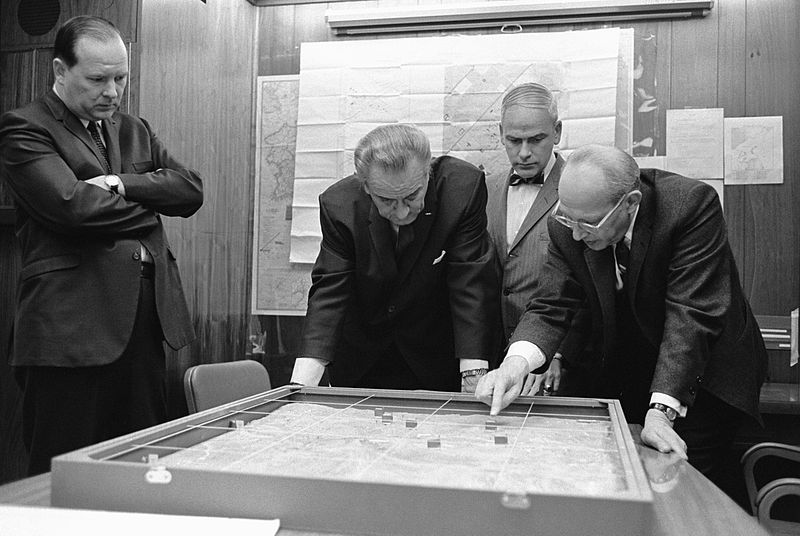

Logevall’s book is the most influential study on U.S. decision-making during the critical years 1964-1965. It challenges the conventional notion that the U.S. decision to wage a major was nearly inevitable, showing instead that Lyndon Johnson had realistic alternatives to escalation.

Neil Sheehan, A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and the America in Vietnam (New York: Vintage, 1989).

Sheehan, an influential journalist during the early stages of America’s war in Vietnam, examines the life and career of John Paul Vann, an American who spent years in Southeast Asia trying to transform South Vietnam into a viable nation capable of defending itself. Vann’s failure captures in microcosm the problems that beset American policy in the area.