By Emily Whalen

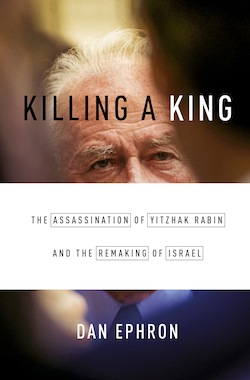

Yigal Amir has never denied assassinating Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Days after he publicly shot Rabin at close range after a peace rally, the young extremist calmly recreated the event for police officers at the crime scene in Tel-Aviv. When police interrogating him informed Amir that Rabin had died from his wounds, Amir was “ecstatic,” asking for liquor to toast his accomplishment. Yet, to this day, conspiracy theories about Rabin’s death abound, with many on the Israeli extreme right suggesting that Shin Bet (or Shabak, the Israeli intelligence agency) orchestrated the killing to drum up sympathy for the Palestinian peace process. With an eye to understanding this surreal state of affairs, Dan Ephron interweaves two narratives: the story of Yitzhak Rabin’s efforts toward building a sustainable peace with the Palestinians and the story of Yigal Amir, whose interpretation of Jewish law and radical conservatism led him to plan and carry out the killing of a prime minister.

Yigal Amir has never denied assassinating Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Days after he publicly shot Rabin at close range after a peace rally, the young extremist calmly recreated the event for police officers at the crime scene in Tel-Aviv. When police interrogating him informed Amir that Rabin had died from his wounds, Amir was “ecstatic,” asking for liquor to toast his accomplishment. Yet, to this day, conspiracy theories about Rabin’s death abound, with many on the Israeli extreme right suggesting that Shin Bet (or Shabak, the Israeli intelligence agency) orchestrated the killing to drum up sympathy for the Palestinian peace process. With an eye to understanding this surreal state of affairs, Dan Ephron interweaves two narratives: the story of Yitzhak Rabin’s efforts toward building a sustainable peace with the Palestinians and the story of Yigal Amir, whose interpretation of Jewish law and radical conservatism led him to plan and carry out the killing of a prime minister.

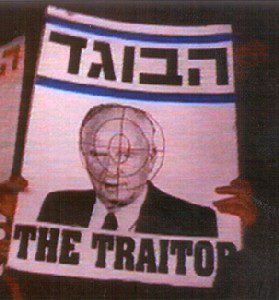

After Rabin and PLO leader Yasser Arafat signed the first Oslo Accords in 1993, the divisions already splintering Israeli society cleaved even deeper, pitting liberal, secular Israelis against a conservative, religious right. By 1994, when Rabin and Arafat signed the Cairo Agreement, those divisions had widened into chasms. The Cairo Agreement initiated the second step in the Oslo Process, limited Israeli withdrawal from the Palestinian territories. Withdrawal further fueled the already blazing anti-Rabin rhetoric in Israel. Ephron writes in lucid detail about anti-Rabin protesters “burning pictures of the prime minister, chanting ‘Death to Rabin’…’Rabin the Nazi’ and ‘In blood and fire, we’re drive Rabin out.’” The right wing of the Israeli political class, Ephron insinuates, took advantage of the charged rhetorical atmosphere to score electoral points. As one particular protest roiled in the streets of Tel Aviv, Benjamin Netanyahu and other Likud leaders silently watched from a hotel balcony—perhaps not actively complicit, but lending an air of legitimacy to violent, angry rhetoric.

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, left, shaking hands with PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat, with U.S. President Bill Clinton in the center at the Oslo Accords signing ceremony, Sept. 13, 1993. (Vince Musi / The White House)

Yigal Amir, a charismatic young activist from a Yemeni Jewish family, believed the Cairo Agreement amounted to treason. His roots in the extreme religious right and connections to the settler community had already placed Amir on Shabak watch lists by 1995, though the agency never scrutinized him individually. Shabak, designed to respond to threats from Palestinian terrorist groups, shifted clumsily to meet the rising menace of Jewish extremism in the years between Oslo I and Rabin’s assassination. Ephron’s book provides sensitive insights into the inner workings of the agency, exploring how bureaucratic inertia supported a series of questionable policy choices. For example, in the aftermath of the assassination, it came to light that a well-known right wing agitator close to Amir, Avishai Raviv, had in fact been an undercover Shabak agent. Questions regarding Raviv’s foreknowledge—and possible encouragement—of the assassination plot, plagued the agency for years (Raviv successfully defended himself against legal charges in 2000 for failing to prevent the assassination – he claimed that he had been operating under Shabak orders and that events spun out of control).

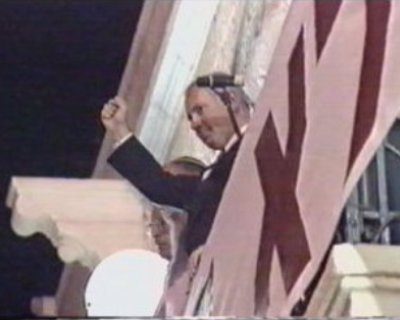

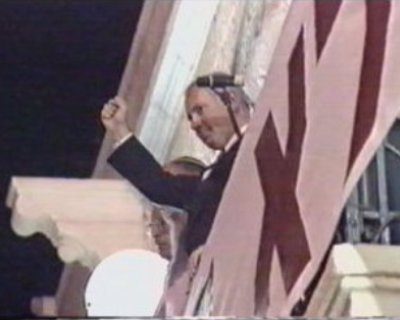

Binyamin Netanyahu speaks at the infamous “Rabin the Traitor” rally in Jerusalem, October 1995

Binyamin Netanyahu speaks at the infamous “Rabin the Traitor” rally in Jerusalem, October 1995

Controversially, Amir justified his desire to assassinate Rabin within the parameters of Jewish law. Ephron explains din rodef, the law of the pursuer, a Talmudic principle permitting extrajudicial killing under extremely specific circumstances. Under din rodef, a Jew may kill a rodef—that is, someone who pursues another with an intent to kill—if absolutely no other means will stop the would-be murderer. Amir openly argued that Rabin’s concessions to Arafat and the Palestinians led to Jewish deaths, thus making Rabin a rodef. Most rabbis agree that din rodef doesn’t apply to public figures, but in Ephron’s interviews, Amir’s brother Hagai suggested the assassin “received at least an implicit confirmation [from right-wing rabbis] that din rodef applied to Rabin.” Confusion over din rodef, Ephron claims, and the rampant conspiracy theories surrounding Rabin’s death have allowed the religious extreme right in recent years to both justify Amir’s act and absolve the assassin of blame.

The latter part of the book develops a third narrative: Ephron’s own efforts to debunk conspiracy theories about Rabin’s murder. Ephron’s certainty about Amir’s sole responsibility wavers in the final chapters as the author attempts to identify a mysterious hole in the shirt Rabin wore the day of the assassination. The hole, troublingly, does not align with bullet wounds described in Rabin’s autopsy—not even Dalia Rabin, the prime minister’s daughter, can say with certainty if Amir was the only shooter. Ephron’s willingness to entertain all possibilities makes for a gripping conclusion.

Since the Rabin assassination, Israeli social and political culture has undergone a fundamental transformation—and a profound polarization. Violent rhetoric, it appears, does have consequences. After Amir murdered Rabin, the seemingly inexorable—although shaky—Palestinian peace process ceased, ushering in the Benjamin Netanyahu era of extreme-right politics. Killing A King offers a provocative perspective on how quickly the world around us can become unrecognizable. Dalia Rabin admits that now, “I don’t feel I’m a part of what most people in this country are willing to do.” Even the recent past, Ephron suggests, is another country.

You may also like Itay Eisinger’s NEP article published on the 20th anniversary of the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin.