An African Slaving Port and the Atlantic World by Mariana Candido (2013)

Cross-Cultural Exchange in the Atlantic World: Angola and Brazil during the Era of the Slave Trade by Roquinaldo Ferriera (2012)

The Atlantic slave trade between Africa and the Americas connected merchants, Portuguese colonists, convicts, and slaves in cultural and economic relationships, reconfiguring the space of the southern Atlantic. The work of Mariana Candido and Roquinaldo Ferriera shows how creolization and the economic prosperity created by the slave trade was a two-way street.

In An African Slaving Port and the Atlantic World, Mariana Candido traces development of Benguela (in today’s Angola) from the first Portuguese expedition in 15th century until the mid-nineteenth century. She studies colonial documents, reports, official letters, censuses, export data, parish records, official chronicles, and oral traditions collected by missionaries and anthropologists. Candido stresses the role of the local population in the Atlantic slave trade. As the demand for slaves increased in Brazil, local interactions with Portuguese officials led to a constant reconfiguration of identity and community in the port city, based on political alliances and economic preservation. Political and social instability of the hinterlands in part led to the exponential growth of the slave trade, displaying the reverberating aspects of the slave trade within the Atlantic realm. Additionally, women played a major role in the development of the slave society within Africa. Mixed marriages became the rule, and African women seized on the chance to apprehend cultural practices and a space of power. These donas controlled a large number of dependents, widows or singles, and became involved in local business, investing in the slave trade after the deaths of foreign husbands. In this regard, Candido shows slavery as a process of negotiation, adaptation, invention, and transformation rather than complete annihilation of African communities.

Candido also argues that creolization was a social-cultural transformation rather merely than an incorporation and assimilation of Western values. Luso-Africans and colonial officials spread Portuguese customs and Catholicism beyond the littoral, accelerating creolization away from coast. Colonial outposts, such as Caconda, attracted people with cultural exchange and the elaboration of new codes transforming cultural diets and colonial institutions. African religion and cosmology remained strong in the hinterland and on the coast in Benguela because they offered explanations and solutions to everyday problems that Catholicism could not address. Additionally, local languages were extremely important to the construct of a slave society. Despite colonial laws against its use, the army, commerce transactions, and the church in the hinterlands used these languages.

Similarly, Roquinaldo Ferriera focuses on the bilateral connections between the Portuguese colonies of Brazil and Angola in Cross Cultural Exchange in the Atlantic World. Through the lens of micro histories, Ferriera pushes back from the macro structural approach to the slave trade to examine the personal trials endured by Africans and their descendants. Throughout the text he suggests an argument similar to Candido’s, in which African institutions were transformed rather than unilaterally corrupted by the slave trade. For example, the use of the traditional African court systems (tribunal de mucano) displays the transformation of the court system and the fluid boundaries between freedom and enslavement in Angola. Additionally, the relationship between belief in the power of the supernatural and accusations of witchcraft as a form of entering into enslavement was employed by Luso-Africans and Portuguese officials alike. If an accused “witch” died, a number of the witch’s relatives were enslaved and sold. As Ferriera points out, the actual number of people enslaved through these accusations would be difficult to precisely enumerate, however, the connection between these accusations and commercial disputes was unmistakable. Moreover, such accusations provide insight into the commonalities between African and colonial officials’ worldviews. Thus, through the lens of micro history, Ferriera claims that Atlantic history is a pluralistic entity in which individuals created their own spaces without strict adherence to the Portuguese institutions.

These two historians transform the way we view the impact of the slave trade. By emphasizing the role of the African populace as well as the Portuguese in the flourishing slave trade, Mariana Candido and Roquinaldo Ferriera redistribute the economic and cultural burden of the Atlantic. Candido and Ferriera demonstrate the cultural exchange between the Portuguese and African, altering the way historians conceptualizes creolization and the formation of slave societies.

You may also like:

The story of Brazil’s most infamous slave rebellion

An environmental and labor history of Brazil’s sugar industry

Photo Credits:

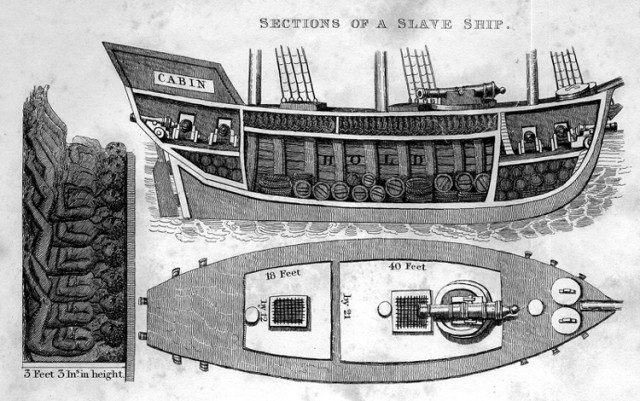

Cross-section of a Brazilian slave ship, taken from “Notices of Brazil in 1828 and 1829” (1830) by Robert Walsh (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

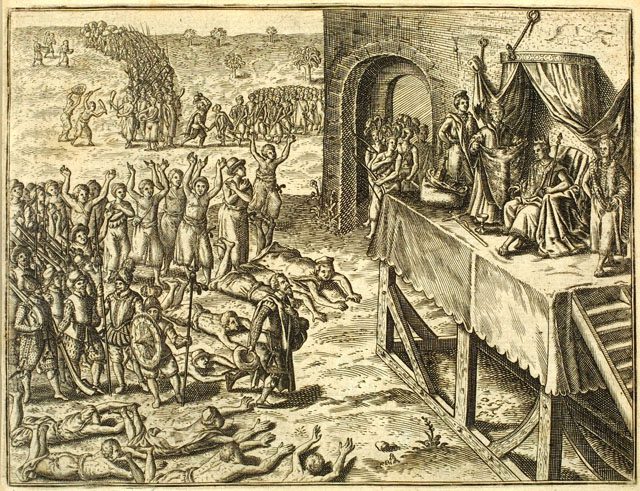

Portuguese officials meet with the Manikongo, who ruled the African Kongo Kingdom (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

A slave ship heading to Brazil, 1835 (Image courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Gallery)

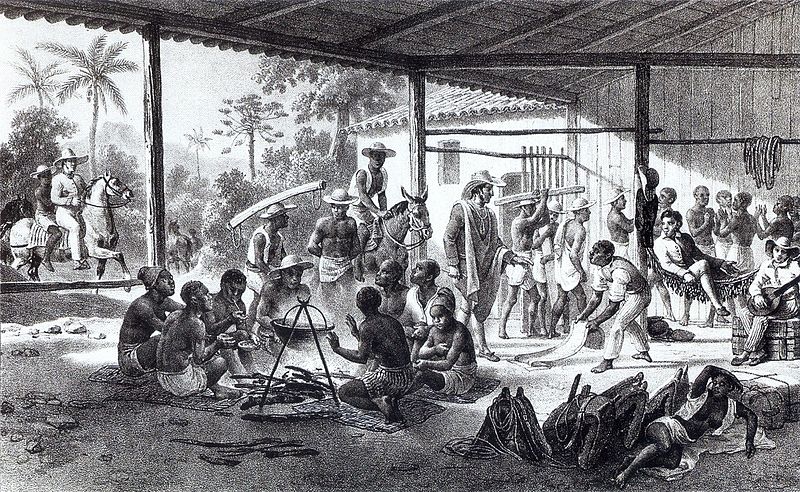

Recently arrived slaves in Brazil on their way to the farms of the landowners who bought them, 1830 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)