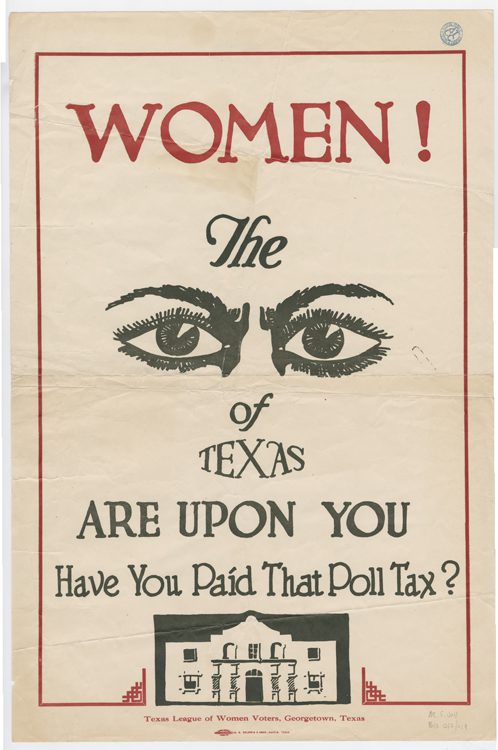

In the Austin History Center, there is a curious poster that demands the attention of “WOMEN!” in red, all-capital letters. Below this, a pair of eyes peer out beneath furrowed eyebrows warning “The Eyes of Texas are Upon You: Have You Paid That Poll Tax?” At the bottom of the poster is the instantly recognizable façade of the Alamo, just above the name of the group responsible for the ad, Texas League of Women Voters, Georgetown, Texas.

The poster is in the Jane McCallum collection. After Texas ratified the 19th Amendment in June 1919, the Texas Equal Suffrage Association became the state chapter of the League of Women Voters, and the local suffrage clubs were encouraged to make that transition as well. McCallum was an Austin-area suffragist who went on to spearhead publicity campaigns for the League of Women voters, lead the Women’s Joint Legislative Council, and serve as Texas Secretary of State under two governors. It is likely she had a hand in this particular poster, but we can’t be sure. In fact, there isn’t even a date on the poster, which scholars and archivists have only dated as being from the early 1920s. Both the Texas Equal Suffrage Associations and the League used maternal appeals to get women to pay the poll tax. They argued that this is how Texas funded public schools, and that “90% of Texas educators are women and need a living wage.”[1] The poster is in line with the WWI-era appeals to women to do their duty as citizens.

The “eyes of Texas” phrase was common enough that it isn’t surprising to see it atop a League poster, but the links between suffragists and the University of Texas ran deep too. Texas suffragists had joined with the university’s alumni to work to impeach anti-suffragist Governor James E. Ferguson in 1917. Ferguson had basically defunded the university for refusing to fire several professors whom he viewed as his political opponents. While Texas was a one-party state, the Texas Democratic Party was divided between progressive, reform Democrats and conservative, anti-prohibition Democrats. The reformers won this fight, impeaching and removing Governor Ferguson, and moderate reformer William Hobby assumed the governorship. Ferguson then ran for re-election against Hobby claiming he had resigned, and that therefore the Texas Senate’s judgement barring him from holding office did not apply to him. It was a close race. With several reformers running, they risked splitting the progressive vote and inadvertently handing the election to Ferguson. To ensure victory, Hobby signed the primary woman suffrage law, allowing Texas women (if they citizens and considered legally white) to vote in the primary but not in general elections. Hobby won, and the leverage afforded by primary suffrage is part of why suffragists were able to get Texas to ratify the 19th Amendment hardly a month after the state suffrage amendment was defeated at referendum. After such a coordinated effort to remove the anti-suffrage governor, using UT’s fight song and Texan imagery like the Alamo made sense to women reformers in Texas.

While the poster isn’t explicitly racist, the poll tax itself was. The poll tax and the all-white primary were the state’s only Jim Crow election laws. Both were passed at the turn of the century, and together they nearly eliminated Black voting in the state and severely reduced poor white voting.

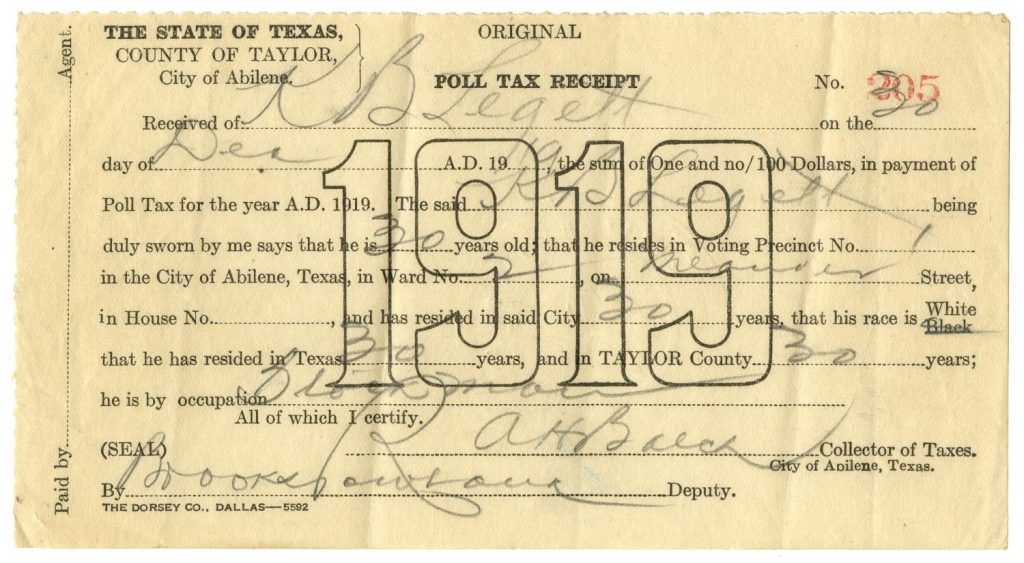

The poster encourages women to pay their poll tax, but the deadline was crucial as well. Poll taxes had to be paid by February 1st each year. Paying the poll tax after that deadline resulted in disfranchisement for the year. Servicemen returning home from WWI in 1919 after the poll tax deadline found themselves effectively disfranchised for up to a year. Suffragists lobbied the state legislature encouraging them to pass a law that would enfranchise newly returned WWI veterans in 1919, and they were successful in getting a law that temporarily allowed veterans to vote on their discharge papers instead of poll tax receipts. [Texas also completely barred servicemen from voting for the length of their service, but that is another story].

The legislature updated both the poll tax and white primary laws shortly after the 19th Amendment became part of the Constitution. Six weeks before the 1920 presidential election, Governor Hobby called the legislature into special session and warned them of the dangers of a “wide open election.”[2] He informed them the 19th Amendment invalidated the state poll tax, which as written only applied to men. The legislature rewrote the poll tax to ensure its constitutionality just a few weeks before the presidential election.

Additionally, the direct primary law left enforcement of the white primary to the Democratic Party, which the state charged with setting its own membership criteria. This was not strict enough for many white legislators who watched in fear as some Black women managed to vote in 1920 and thereafter. The state legislated the all-white primary itself in 1923. In doing so, they overstepped their bounds and created the white primary’s Achille’s heel, which the Supreme Court would eventually use to strike it down entirely in Smith v. Allwright (1944). It is not a coincidence that the state acted to shore up their only two Jim Crow voting restrictions after woman suffrage was enacted by the 19th Amendment.

Finally, we know that at its earliest the poster was made in 1920 and more likely 1921 or later. If it is from 1921, one of the amendments on the ballot would have disfranchised (mostly Mexican and German) immigrant voters, while allowing spouses to pay each other’s poll taxes, essentially making it easier for white, middle-class women to vote. Nearly two-thirds of the country allowed immigrants who had declared their intention to become citizens to vote at some point in their territorial or state history. In much of the south, declarant immigrant voting was a Reconstruction reform intended to counter the vote of unreconstructed white southerners. In 1919, a similar state constitutional amendment that would have enacted woman suffrage but eliminated declarant immigrant voting in Texas failed at referendum. In 1921, once white women could vote, the immigrant disfranchising amendment passed.

[1] September 30, 1919, TESA to County Chairmen, [newsletter], Box 5, Folder 12, Jane Y. McCallum Collection, Austin History Center.

[2] State of Texas, 36th Legislature, Journal of the House of Representatives, 4th called sess., 1920, 5.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.