Adrian Wilson writes an interesting chronicle of man-midwifery’s emergence in England. His research is based on an exhaustive analysis of manuscripts, newspapers, and the memoirs of surgeons, physicians, and midwives. He not only explains the rise of men in an otherwise female-dominated field, but explores the practice of traditional midwifery. Prior to the mid-eighteenth century, childbirth, from labor to the lying-in chamber (a darkened room where the mother rested for one month after delivery) was an exclusively female space. With few exceptions, male surgeons only intervened to extract a possibly dead baby in order to save a mother’s life. They achieved this operation through the use of hooked instruments, such as the crotchet and forceps, which mutilated the baby. While midwives delivered living babies, male practitioners brought forth dead ones. By the mid-1740s, surgeons increasingly used the forceps and vectis to achieve successful births. The male sphere, thus, moved from traditional obstetric surgery to the new “man-midwifery.” The need for instruction on the forceps’ effective use soon resulted in the emergence of lying-in hospitals that increasingly gave men access to normal births.

Adrian Wilson writes an interesting chronicle of man-midwifery’s emergence in England. His research is based on an exhaustive analysis of manuscripts, newspapers, and the memoirs of surgeons, physicians, and midwives. He not only explains the rise of men in an otherwise female-dominated field, but explores the practice of traditional midwifery. Prior to the mid-eighteenth century, childbirth, from labor to the lying-in chamber (a darkened room where the mother rested for one month after delivery) was an exclusively female space. With few exceptions, male surgeons only intervened to extract a possibly dead baby in order to save a mother’s life. They achieved this operation through the use of hooked instruments, such as the crotchet and forceps, which mutilated the baby. While midwives delivered living babies, male practitioners brought forth dead ones. By the mid-1740s, surgeons increasingly used the forceps and vectis to achieve successful births. The male sphere, thus, moved from traditional obstetric surgery to the new “man-midwifery.” The need for instruction on the forceps’ effective use soon resulted in the emergence of lying-in hospitals that increasingly gave men access to normal births.

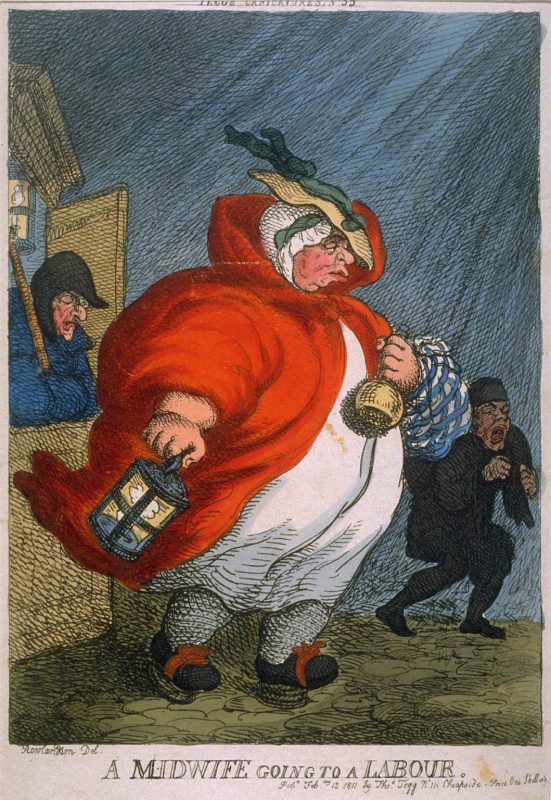

The establishment of a “lying-in-fund” induced poor mothers to submit themselves as teaching specimens to man-midwives. By 1750s, the lying-in hospitals became a permanent feature of England’s hospital system. Its hierarchy elevated the man-midwife over the midwife. By the nineteenth century, man-midwives assumed a new name, obstetricians, and received “onset summons” in lieu of midwives. Gradually, midwives learned the use of the forceps in order to match their male rivals. In 1902, after a protracted struggle, midwives gained professional status and normal deliveries returned to their realm.

1811 Thomas Rowlandson cartoon lampooning England’s male midwives (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, France)

The loophole in Wilson’s impressive text lies in his conclusion that women’s choices spurred the rise of man-midwifery. He neglects the fact that women were merely reacting to a new development that offered more positive results in cases of difficult births. Lying-in hospitals offered few options for poor women as man-midwives already dominated these facilities from their early years. Wilson’s conclusion also undermines the power of newspapers and other publications in constructing social behaviors. From the 1740s, midwives were criticized for failing to summon the man-midwife and his forceps at the onset of labor. These public criticisms by prominent man-midwives influenced collective attitudes. Thus, understanding the rise of man-midwifery requires looking beyond women’s choices to broader developments in society. Nonetheless, Wilson’s book offers a fascinating read for anyone interested in the evolution of midwifery and reproductive health.

More on Early Modern Europe:

Brian Levack interprets the historical meaning of possession and exorcism

And Jessica Luther explains how a seventeenth-century English diarist started tweeting