by Zachary Carmichael

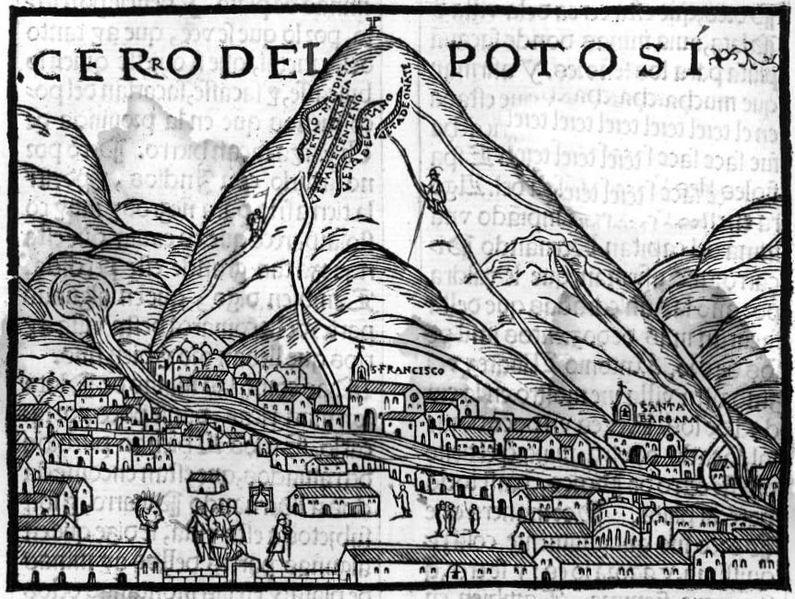

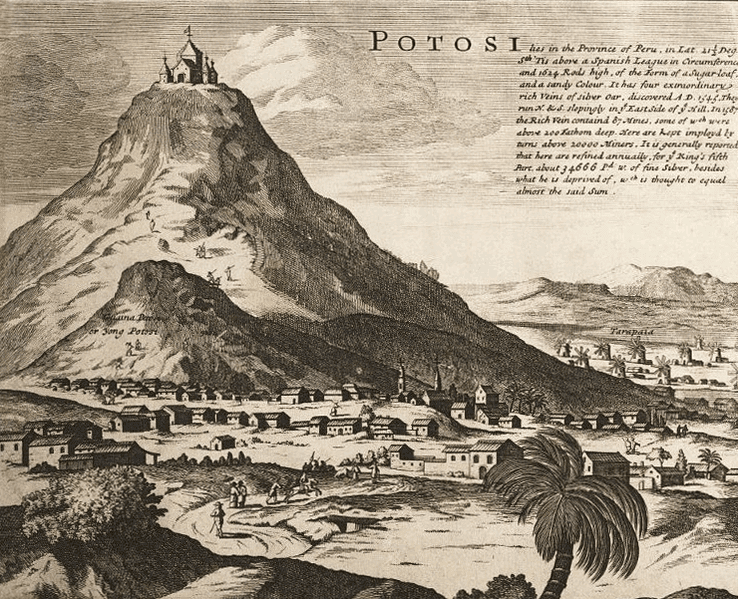

In only a few decades during the seventeenth century, the Spanish American colonial city of Potosí, in modern-day Bolivia, grew from a small settlement to a metropolis of almost 200,000. With twice the total population of all of Britain’s North American colonies, Potosí became one of the largest cities in the Americas despite being at an elevation of over 13,000 feet. This expansion centered on the massive silver mines at the nearby Andean mountain of Potosí that fueled Spain’s imperial ambitions. How did the city’s infrastructure keep pace with this startling urban growth?

With twice the total population of all of Britain’s North American colonies, Potosí became one of the largest cities in the Americas despite being at an elevation of over 13,000 feet. This expansion centered on the massive silver mines at the nearby Andean mountain of Potosí that fueled Spain’s imperial ambitions. How did the city’s infrastructure keep pace with this startling urban growth?

Jane Mangan’s Trading Roles focuses not on the Indian, African, or Spanish silver miners, but on the local urban economy, run by poor, mostly indigenous men and women, that kept the city functioning. She argues that Potosí, with its extremely active market, fostered a degree of social mobility that was unknown in the rest of the Americas and Europe. It was the indigenous population (whom Mangan intentionally calls Indians), particularly women who shaped the city’s economy. In their struggle against Spanish competition and the colonial bureaucracy, natives used urban entrepreneurship to power Potosí’s growth.

Trading Roles traces Potosí’s development from the middle of the sixteenth century, discussing the growth of an indigenous business market among natives who had left their communities for the silver capital. Leaders tried to regulate commercial space in the city to curb perceived excessive drinking among mine workers and to maintain social order. The commercial system created by unmarried Indian women was at the heart of the Potosí economy. Mangan uses several striking examples of their social mobility and entrepreneurship. Indian women were able to make a comfortable life for themselves by running bakeries and breweries and loaning money to customers. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, external economic forces caused Potosí to enter a period of irreversible decline. The end of the silver boom devastated the economy and cut the population in half, marking the end of this extraordinary social mobility.

The book is extremely well-researched, ably drawing upon the surprisingly large number of sources available about the city. Mangan draws upon notarial records from the old colonial mint in Potosí, minutes of city council meetings housed in Sucre, Bolivia, and imperial archives in Seville. Although records of business transactions between indigenous women and their customers are rare, Mangan compensates by finding contextual evidence of this economic activity. Her research demonstrates the crucial role of court and notarial records in recreating the lives of early modern non-elites.

The unique urban character of Potosí was exceptional in the seventeenth century, so it is difficult to apply Mangan’s arguments about social mobility to the rest of Spanish America and the wider early modern world. The discussion of the growth and decline of Potosí lacks the incisive analysis of the sections on Indian women entrepreneurs. Despite this, Trading Roles is an important contribution to the study of urban history and social mobility in colonial Spanish America. Mangan’s conclusions offer a counterpoint to prevailing theories about the economic role of the indigenous populations in the Americas and challenge conventional views about European control of colonial urban economies.

Photo credits:

All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

You may also like:

Zach Carmichael’s other reviews on Spain’s colonial posessions in Latin America:

Patrons, Partisans, and Palace Intrigues and Barbaros: Spaniards and their Savages in the Age of Enlightenment.