By Judy Coffin

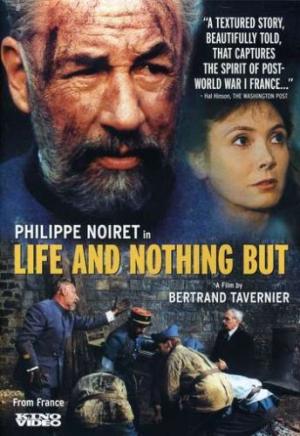

French historians love this film. It’s hard to convey the horrors of what was long called The Great War: the almost unimaginable losses at battles like Verdun and the Somme; the mobilization of whole economies, states, and societies to supply those battles and to replenish the men and material afterwards; the stench of rotting corpses (human and animal) in the trenches; and the grinding boredom of trench life – interrupted by terrifying bombardment or the dreaded command to go “over the top,” through the mud, barbed wire, and, further on, the machine gunners on the enemy side.  Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (with Kurt Douglas, 1957) captures some of the view from the trenches. So does PBS’s multi-disc documentary: The Great War and the Shaping of the Twentieth Century. Not surprisingly, though, the most popular films about World War I – like the brilliant Lawrence of Arabia — are set far from the un-cinematic slog of the western front. Life and Nothing But is set on the front, but after the war, where the French are trying both to tally their losses and commemorate their victory. Both projects are heartbreaking and, in some important sense, impossible. That’s the point, and the film captures one of the tragedies of war and a more specific tragedy of twentieth-century French history.

Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (with Kurt Douglas, 1957) captures some of the view from the trenches. So does PBS’s multi-disc documentary: The Great War and the Shaping of the Twentieth Century. Not surprisingly, though, the most popular films about World War I – like the brilliant Lawrence of Arabia — are set far from the un-cinematic slog of the western front. Life and Nothing But is set on the front, but after the war, where the French are trying both to tally their losses and commemorate their victory. Both projects are heartbreaking and, in some important sense, impossible. That’s the point, and the film captures one of the tragedies of war and a more specific tragedy of twentieth-century French history.

Philippe Noiret plays French Major Delaplane, charged with trying to discover the fates of the over 300,000 French soldiers missing at the end of the war. Most of them were dead, it would turn out. 1.4 million French soldiers were killed, out of 8.4 mobilized. Delaplane presides over a ramshackle, improvised office filled with clerks compiling lists of the dead and descriptions of the missing. In the psychiatric hospital next door, teams of doctors work with soldiers whose minds have been destroyed: trying to get them to walk, to speak, or to recover bits of memory that might help to identify them. In the surrounding countryside, crews dig in a tunnel that had been mined by the Germans, destroying a Red Cross train and the wounded it was carrying. On designated days families of the missing are permitted on site, and they comb through long tables of rings, watches, and occasionally photographs searching for bits and pieces of their loved ones’ lives.

Into this melancholy scene come two women. Irène de Courtil, (Sabina Azena) wealthy and beautiful, is looking for her missing husband and the much younger, middle-class Alice (Pascale Vignal) searching for her fiancé, whom she met while he was a soldier. Alice had taught school during the war, but then had to give up her post to a veteran returning from the front. (This is a nicely understated rendering of the government’s policy after World War I.) She now is working in a café in the area near Delaplane’s project, hoping for news.

No spoilers here, and the plot matters! But you will find love, of course, and deception, class resentments, and cynicism (softened by love). It’s not grim, but haunting. It’s hardly an action film –- I don’t want you to be disappointed — but then World War I was not usually an action war. It’s about a country whose past is mined, literally and figuratively, but which is compelled to return to that past. It’s about memory, a subject that has fascinated historians for decades now. It’s smart about commemoration: Tavernier makes us ask what the French state wants to commemorate and how, what the families want to remember, and what Delaplane, Irène, and Alice, respectively, are looking for. It’s acerbic about the politics of commemoration too. Delaplane has to produce a body for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. “Ah non,” the government’s representative says refusing one of the bodies that the major offers him: “certainly not a black!” Why not? Roughly half a million troops from France’s colonies fought in the war.

France’s victory cost more than the country could pay. Reparations would prove a dangerous illusion. We know this, and we know what happened in a few decades later. But this film doesn’t preach or offer general lessons: it looks closely at a grieving culture, trying to gather up the pieces and move on – to what we now know will be another war.

More great French war films:

François Truffaut, The Last Metro

Marcel Ophuls, The Sorrow and the Pity

Marcel Ophuls, Hotel Terminus: the Life and Times of Klaus Barbie

Jean-Pierre Melville, Army of Shadows

Joseph Losey, Mr. Klein

Louis Malle, Au Revoir les Enfants