As a French historian, I was bombarded with questions from friends, family members, and even strangers about whether I was excited to see “Les Miz,” the film version of the wildly popular stage musical, which was released in December. For some reason, knowing that someone who studies French history is excited to see Les Misérables makes people want to see the film more. A film adaptation of a stage play is always a risky venture. A film adaptation of a stage play, that itself was a musical adaptation of  a novel, especially such a well-known and prodigious novel like Victor Hugo’s 1862 Les Misérables, is even riskier. But after the opening weekend alone, the new Les Misérables is already considered a commercial success with an estimated $18.2 million in box office receipts and many favorable reviews. Overall, Les Misérables is an intense, moving, and beautiful film that will undoubtedly receive numerous award nominations in the next few months and I highly suggest that you add it to your holiday season watch list. But while the 2012 Les Misérables is a moving and entertaining film musical, it lacks historical context and may leave viewers scratching their heads about basic plot elements.

a novel, especially such a well-known and prodigious novel like Victor Hugo’s 1862 Les Misérables, is even riskier. But after the opening weekend alone, the new Les Misérables is already considered a commercial success with an estimated $18.2 million in box office receipts and many favorable reviews. Overall, Les Misérables is an intense, moving, and beautiful film that will undoubtedly receive numerous award nominations in the next few months and I highly suggest that you add it to your holiday season watch list. But while the 2012 Les Misérables is a moving and entertaining film musical, it lacks historical context and may leave viewers scratching their heads about basic plot elements.

The film follows the life of paroled criminal, Jean Valjean (Hugh Jackman) in his struggle for redemption, from 1815 to the June Rebellion of 1832. After breaking parole, Valjean is chased by Police Inspector Javert (Russell Crowe) for nearly fifteen years. Under one of his assumed identities as a factory owner and mayor of Montreuil, Valjean meets Fantine (Anne Hathaway), his former factory worker and now a prostitute who is dying. Valjean promises Fantine that he will rescue her child, Cosette (Amanda Seyfried) from her life with a cruel innkeeper, Thénardier (Sacha Baron Cohen) and his wife, Madame Thénardier (Helena Bonham Carter), and raise Cosette as his own. Escaping from Javert twice, Valjean and Cosette move to Paris where Cosette falls in love with Marius (Eddie Redmayne), a French Republican and member of the “Friends of the ABC.” Marius, along with the leader of the “Friends of the ABC,” Enjolras (Aaron Tveit), plan a rebellion against Louis Philippe’s monarchy that will coincide with General Lamarque’s funeral. This rebellion, known as the June Rebellion of 1832, is chronicled in the last half of the film, with Marius, Valjean, and Javert all becoming involved.

Hooper’s decision to focus on the actors’ faces and upper bodies in lieu of wider shots that could establish the Parisian setting, was particularly striking in comparison to other musicals. When you attend a musical in a stage theater, you typically focus on the cast as a whole, their interactions with each other, and the setting, but rarely on the facial expressions of the actors since they are far away. By employing so many close-ups Hooper brings attention away from the setting, nineteenth-century Paris, and places it onto the individual characters. Shockingly, the only time the viewer may

really realize that Les Misérables is set in Paris is during Javert’s two solos when he teeters precariously on the ledge of the Palais de Justice in front of Notre Dame and later on a bridge high above the Seine. Even then, the viewer only sees a quick and blurred view of Paris at night. Since much of Victor Hugo’s original novel, Les Misérables, describes the deteriorating living conditions of the poor in the increasingly industrial and dirty Paris, this was rather disappointing. I would have preferred to see Paris as a character itself, as it is in the novel, instead of the out-of-focus background that Hooper created.

This is not the sole fault of the current filmmakers as there is little historical context in the original musical composed by Alan Boubliland and Claude-Michel Schönberg for the stage in 1980. Instead of focusing on republicanism, the failures of the 1789 Revolution, antimonarchism, the increased suffering and austerity of the poor, the changing nature and architecture of nineteenth-century Paris, and issues pertaining to religion that were fixtures in Hugo’s Les Misérables, Boubliland and Schönberg chose to concentrate on Hugo’s more romantic themes of individual redemption and simplified ideas of social justice as they are more easily expressed in emotionally powerful songs. By continuing to have these themes drive the plot of the movie, Hooper and William Nicholson, the main screenwriter who adapted the musical for film, overlook Hugo’s sharp political criticism and even the reasons why particular characters were so angry and so opposed to monarchy. Although many viewers are likely to be satisfied with the romantic plot and the great songs, many, especially those unfamiliar with the historical context, are undoubtedly perplexed. Throughout the nearly three-hour film, my dad nudged me and whispered, “Why is Cosette living with the Borat guy (Thénardier played by Sacha Baron Cohen) and his wife? Why are the boys mad? Who’s General Lamarque? Why does it matter that he died? Who’s Louis Philippe? Is this in Paris? When is this?” In fact, exiting the movie theater I overheard a woman asking her friend, “So that was the French Revolution and it was unsuccessful?”

This woman’s question pointed out a common misconception about Les Misérables: that it is set against the backdrop of what historians call the French Revolution which began in 1789. That revolution lasted until 1799 and at first overthrew Louis XVI’s absolutist monarchy in favor of a constitutional monarchy and later, after Louis XVI’s execution in 1793, created a republic, or a democratically elected

government without a monarch. But the 1789 revolution is not the backdrop for Les Misérables. Instead, Hugo’s novel and the musical take place during The Bourbon Restoration (1815-1830) and the very beginning of the July Monarchy (1830-1848). Although Hooper includes a quick five-second text at the beginning of the film that reads, “1815, twenty-six years after the Revolution there is once again a French king on the throne,” few understand the implied, complicated historical context these words are supposed to provide.

Unless you just took a course on French history, you might not remember that 1815 marked the end of the First French Empire. Following his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo and his subsequent exile to St. Helena, in 1815 Napoleon abdicated as Emperor. From 1815 until 1848, France was ruled by a monarchy, but unlike the earlier absolutist French monarchy, often referred to as the “Ancien Régime,” the Restoration was a constitutional monarchy that began with Louis XVIII who was later succeeded by Charles X. Under the Charter of 1814, a constitutional monarchy meant that even though the king still held considerable power over policy-making, his legal decrees had to be passed and legitimated by Parliament before they went into effect. But in 1830, Charles X tried to amend the Charter of 1814 to restrict the press and create a more absolutist form of government. Unhappy with this attack on their rights, many Parisians mobilized in July 1830 and forced Charles X to abdicate his throne in what became known as the July Revolution, or the Trois Glorieuses in French, referring to the three days of the uprising. The July Revolution is only glossed over in the novel and not addressed in the musical though it impacted the future June Rebellion of 1832 which is showcased in Les Misérables.

Louis Philippe succeeded Charles X and was initially very popular. But, like constitutional monarchs before him, he became more conservative, wanting to increase monarchical power. Working and living conditions of the poor rapidly deteriorated under Louis Philippe and the income gap between the working classes and the bourgeoisie widened considerably, resulting in increased opposition, antimonarchism, and civil unrest. One of the leading members of the opposition was Jean Maximilien Lamarque, referred to in the novel and the musical as “General Lamarque.” Once an enthusiastic supporter of Louis Philippe, Lamarque quickly became one of his biggest opponents, insisting that Louis Philippe’s form of constitutional monarchy was an affront to civil rights and political liberty. In the novel, General Lamarque is portrayed as a champion of the poor, working classes. Although this is implied in the film, his role beyond being a supporter of the poor is left unexplained, leading many to wonder why his death was the catalyst to the unsuccessful June Rebellion led by Enjolras, Marius, and other “Friends of the ABC.” Led by Parisian Republicans, most of whom were schoolboys, who wished to incite another rebellion like that of July 1830 and dissolve the monarchy, the June Rebellion was defeated and resulted in an estimated 800 casualties in Paris. Despite Enjolras mentioning that the “other barricades have fallen,” in the film we do not get a sense of just how many other barricades there were or how many other people were involved in the uprising. Only about twenty men are shown with Enjolras and Marius in the film, leading the viewer to believe that this was nothing more than an attempt by a handful of schoolboys to overthrow the government, when in actuality it was a somewhat larger movement than suggested. Their motivations for wanting to overthrow the government are only superficially explained with the song “Do You Hear the People Sing?” Although a sort of battle cry in the film, the song does not actually explain why these men, French Republicans, were opposed the constitutional monarchy.

Victor Hugo, himself, was originally a royalist and a member of Louis Philippe’s government, but became discontent with the monarchy. In the 1830s he supported republicanism that favored a constitutional form of government with more freedom of the press, increased self-government, and a fairer justice system. When the Revolution in 1848 brought an end to monarchy and created another new French republic, Hugo was elected to the Constitutional Assembly and the Legislative Assembly, taking an active role in the elected, republican government. However, this Second Republic was short lived. Napoleon III, originally elected as President of the Second Republic in 1848, took power as a monarchical ruler in 1851 and declared himself Emperor in 1852. Following this, Hugo publically declared Napoleon III a traitor and was exiled to Guernesy. It was here, during his exile, that Hugo wrote Les Misérables in the 1850s and early 1860s. Therefore, Les Misérables was not only intended as a political criticism of Louis Philippe’s reign in the 1830s and 1840s, but also of Napoleon III’s rule over France in the 1850s. Hugo hoped that Les Misérables would reveal the social injustices that occurred under any monarchical or imperial rule, spurring support for the French Republic. By focusing on the death and suffering of the poor and the revolutionaries, Hugo also made sure to explain that more freedom would come with a price and attempts to overthrow a government would sometimes be unsuccessful, but were worth fighting for.

The musical not only omitted Hugo’s scathing political criticism of Louis Philippe, and Napoleon III, but also the anticlerical sentiments espoused in Hugo’s novel. With the reestablishment of the monarchy in 1815, the Roman Catholic Church once again became a powerful force in French politics and society. Hugo displays the importance of the Catholic Church to French society during this period by emphasizing the importance of Bishop Myriel to his community and by staging numerous scenes in convents and other religious houses. However, his inclusion of these characters and

scenes is not to be confused with praise. As he became increasingly opposed to monarchy, Hugo also became increasingly opposed to the Church. Despite being raised as a Catholic and remaining a believer (the last line of his will reads “Je crois en Dieu” or “I believe in God”), he found little use for organized religion and often viewed the Church as responsible for increasing the suffering of the poor thanks to its reduction in public services and what he saw as a general apathy of the people. But, based on the musical and the film, one might conclude that Hugo was a strong supporter and admirer of the Catholic Church.

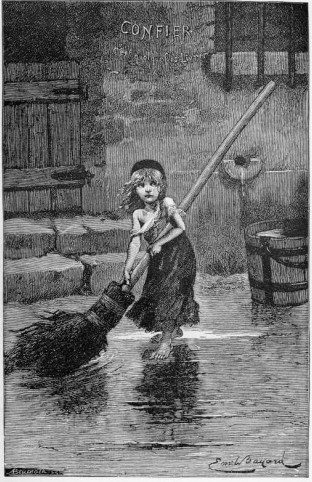

Another issue that could have been better addressed in the film was the peculiar living situation of Fantine and Cosette. We learn early on that Fantine, who initially is working at Valjean’s factory, has an illegitimate daughter who she sent to live with an innkeeper, Thénardier, and his wife. After seeing the film, both my dad and one of my friends asked me, “Why in the world would Fantine send her daughter to live with an innkeeper and pay for it if Cosette works for them?” Sending children, especially girls, to live and work in other households was a rather common practice throughout this era. Similar to indentured servitude, young girls were employed as domestic servants in households throughout Europe. Paid at the end of their terms, these domestic servants were usually allowed to live in the household in provided quarters and, under coverture laws, were legally dependent upon the head of the household they lived in. For many single mothers like Fantine who could probably not afford to care for Cosette completely, let alone watch her during the day, sending a child away to work and live would have been a difficult, yet necessary decision.

Les Misérables is a musical masterpiece and a thoroughly enjoyable movie-going experience, even without the historical context. However, if you are distracted by lingering contextual questions, I suggest that you browse the Wikipedia page on Les Misérables (the novel) before you see the film. This article will provide you with a brief synopsis of the plot, the characters, and enough historical context so you do not feel lost. And maybe forward that information to your friends and family beforehand so you aren’t the one being nudged every few minutes for answers to historical questions.

Photo Credits:

An 1886 engraving of the Les Misérables character “Cosette” (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Louis Philippe I, the King of France from 1830 to 1848 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Painting of the July Revolution of 1830 in Paris (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

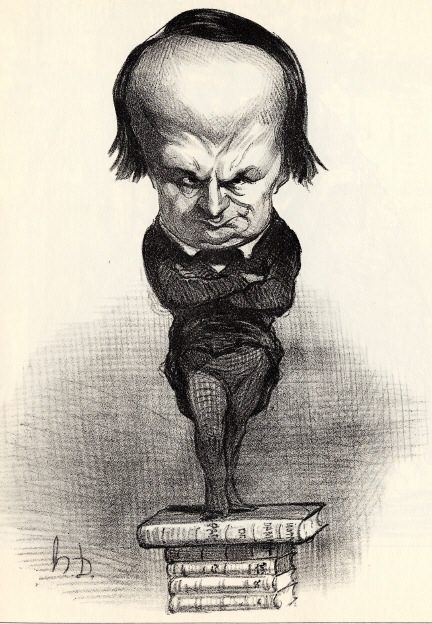

1849 caricature of Victor Hugo (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines