By J. Taylor Vurpillat

The upsurge in public awareness of economic inequality since the 2008 financial crisis has refocused attention on the Gilded Age and Progressive Era in American history, a period defined by wealth disparities that parallel our own. The problem with our search for historical analogies is that we often examine the past within the context of our individual assumptions, finding what we want to find—a process cognitive psychologists call confirmation bias. Given the need for well-observed general history to guide our inquiry, it is gratifying that we have Michael McGerr’s A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870-1920.

The upsurge in public awareness of economic inequality since the 2008 financial crisis has refocused attention on the Gilded Age and Progressive Era in American history, a period defined by wealth disparities that parallel our own. The problem with our search for historical analogies is that we often examine the past within the context of our individual assumptions, finding what we want to find—a process cognitive psychologists call confirmation bias. Given the need for well-observed general history to guide our inquiry, it is gratifying that we have Michael McGerr’s A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870-1920.

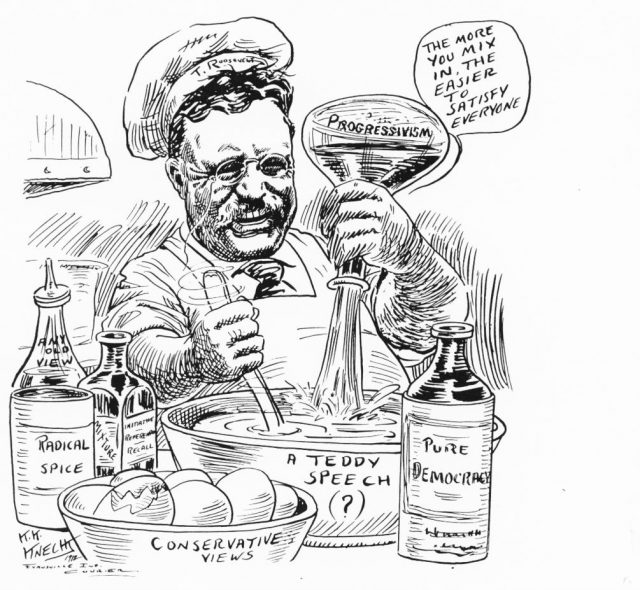

Until recently, historians of the era had nearly given up on synthesizing the fractal array of differing impulses behind progressive reform efforts. A large group of progressive reformers wanted to harness the unbridled energy and influence of industry in American life. Other reformers, such as Jane Addams and Jacob Riis, were more interested in ameliorating the day-to-day problems of America’s expanding immigrant working class. Another faction wanted good government, female suffrage, prohibition, and a world safe for democracy. The frustration of making sense of the period has been expressed by John D. Buenker and Peter G. Filene who argued in various essays that, beyond sharing a general dissatisfaction with Industrial America, reformers were too disparate to share common motives for reform.

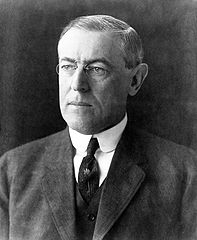

In a sustained and elegant effort, Michael McGerr’s A Fierce Discontent has swept away much of the frustration of the previous generation. The argument at the center of the book makes a clear case that the array of progressive reform impulses were, in fact, quite unified when viewed through the lens of class. It was the horror with which many middle-class Americans viewed the personal excesses of the industrial upper class and the tumultuous and inharmonious society the “upper ten” had imposed on other Americans that inspired progressive reformers and ultimately the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

Given his argument based on class, McGerr takes a few cues from Karl Marx—and many more from Sigmund Freud by way of Richard Hofstadter, the notable mid-century American historian. In the 1950s, it was Hofstadter who made the argument that the progressive impulse of the early twentieth century was driven by a status anxiety among middle-class Americans unsure of their place in the new industrial order.

McGerr has updated this brilliant but dashed-off argument, developing a deeper, more subtle analysis grounded in the primary sources of the era. For example, he takes time to portray the ethos of maximalist individualism that defined the industrial upper class at the turn of the century. He delves into the amusing details of an extravagant 1897 costume ball held for New York’s high society amid the worse economic depression before the 1930s. This set piece, which included reports of the backlash to the ball in America’s leading newspapers, perfectly illustrated the growing rift between a sober, civic-minded middle class and the excess and individualism of the upper class. As McGerr makes clear, it was the culture of the upper class—half perversion and half repudiation of Victorian virtues — that repelled “the middle class enough to transform them from respectable Victorians into radicals.”

In developing this argument, McGerr challenges the views of both the New Left in the 1960s, that progressives were nothing more than petty bourgeois defenders of the new industrial elite—and from more recent arguments of the New Right that progressives of the era were socialists in all but name.

There are many strong points in McGerr’s telling. Foremost among these is the way he brings progressive support for segregation into his larger argument. Many progressives supported legal segregation. Indeed, in the first decades of the twentieth century segregation intensified—and not only in the South. These efforts, McGerr argues, showed the limits of social transformation imagined by progressive reformers. More importantly, it demonstrated the ways in which progressive desires for order took primacy over ideas of racial equality and integration. Segregation was a way to “halt dangerous social conflict that could not otherwise be stopped,” according to McGerr.

The second strength of the book is the extensive use of sources embedded in a tightly organized narrative that covers both the major accomplishments and small victories of the progressive movement. As readers, we witness both the trust-busting heroics of Theodore Roosevelt and the long struggle of Lillian Wald and others to limit child labor. Most importantly, we are given a vantage of changing industrial society from the viewpoint of those whose everyday lives were most dramatically altered. Rahel Golub, the young daughter of German-Jewish immigrants, spent six days each week sewing and serving her family until settlement workers exposed her to a foreign world known as “uptown”—a world so different from the working-class neighborhoods of lower Manhattan that it seemed to her a foreign country.

A third strength is the discussion of the obstacles that challenged and ultimately defeated this army of crusading middle-class reformers. Progressivism, McGerr contends, offered middle-class Americans the utopian promise of a perfected society. Because such a transformational vision demanded so much of Americans, it proved to be an unrealistic vision that led to inevitable letdowns. Reform did not create a harmonious middle-class paradise. Nevertheless, the progressive movement captured the mainstream of American politics and public spirit and its downfall required more than half-met expectations. Despite progressive legislative triumphs against corporate power, the maximalist individualism of the upper class proved more difficult to contain. The leisure class, some of whom had decamped for Europe at the turn of the century, returned in force in the 1920s as American involvement in the First World War discredited the reform-minded collective action of Woodrow Wilson and others.

Middle-class reformers also faced growing resistance from a second, new form of individualism emerging from the working-class neighborhoods of America’s industrial cities. Higher real wages and increased leisure time—a progressive triumph—gave rise to a series of new popular entertainments that drew young workers into jazz-filled dance halls, amusement parks, and cathedrals constructed for the era’s most magnificent amusement—moving pictures. The disillusionment with progressive efforts to remake society and the world—along with the resurgence of individualist sentiment on two fronts ultimately doomed progressive reform to the margins of American public life after 1920.

If there are faults in this sweeping history of the Progressive Era, they are few. One might quibble with McGerr’s repeated use of the term “the middle class” to refer to progressive reformers. It is useful but progressive reformers represented only a portion of the middle class and some development of the other sentiments across the middle-class political spectrum would have been helpful. It is hard to explain the popular election of anti-reform Republicans in the 1920s without a more explicit definition of the middle class.

A Fierce Discontent, shows historian Michael McGerr as master of both subject and craft. The book demonstrates his command of the intimate details that illuminate the past and of the analytical perspective that gives these details meaning. As far as historical insights that may help us understand our own times, McGerr’s argument highlights the fact that out of disparate material circumstances disparate sentiments, values, and cultures emerged. The problem for progressives then was that these cultures in conflict were all parts of a single nation, society, and political system.

Michael McGerr, A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870-1920 (Free Press, 2003)