In The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Giancarlo Casale contests the prevailing narrative that characterizes the Ottoman Empire as a passive bystander in the sixteenth-century struggle for dominance of global trade. Using documents from archives in Istanbul and Portugal, Casale shifts our attention east and demonstrates that the Ottomans were actively engaged as rivals to the Portuguese for control of the lucrative spice trade and sea lanes of the Indian Ocean.

In The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Giancarlo Casale contests the prevailing narrative that characterizes the Ottoman Empire as a passive bystander in the sixteenth-century struggle for dominance of global trade. Using documents from archives in Istanbul and Portugal, Casale shifts our attention east and demonstrates that the Ottomans were actively engaged as rivals to the Portuguese for control of the lucrative spice trade and sea lanes of the Indian Ocean.

Casale’s study is a reaction against two historiographical trends: the first is a Eurocentric version of history in which the so-called Age of Exploration is posited as a purely European phenomenon, conditioned by the intellectual tradition of the European Renaissance and focused on New World colonization. This perspective focuses on the opening of direct trade between Europe and Asia as the catapult that launched Europe forward and started the Ottoman Empire’s slow road toward decline and eventual demise as the “sick man of Europe.” The second is the new trend toward a non-Eurocentric view of world history, that seeks to write the history of the global community that is independent of Europe. The Ottoman Empire tends to get short shrift in the early modern period in both of these narratives because it did not focus on Atlantic exploration or colonization. Indeed, a cursory review of nearly every map published in world history textbooks that depicts trade routes in the 16th and 17th centuries will show a swirl of arrows around, but never through, Ottoman and Safavid lands in the eastern Mediterranean.

Casale proposes instead that Ottoman participation in the Age of Exploration focused on maintaining, expanding, and defending Indian Ocean trade against the Portuguese expansion there. For the Ottomans, the Indian Ocean seemed likely to be far more lucrative than the colonization of a new continent whose economic viability was anything but assured. The income was substantial and the Ottoman and Portuguese navies were well-matched, challenging the Eurocentric narrative that suggests that European exploration was boosted by superior technology and weaponry.

While the phenomenon of Indian Ocean trade in the pre-colonial era has been well documented by Janet Abu-Lughod, Andre Frank and others, Casale provides the Ottoman perspective for the first time through new discoveries in the Ottoman archives. We are introduced to previously unknown heroes and villains, giving familiar events new interpretations. The Ottomans were introduced to this new milieu in 1517 following their conquest of Egypt, a province that had grown rich from its geographic position at the head of the Nile, the head of the Red Sea, and from the their monopoly on trade between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean world. The Portuguese sought to challenge Egyptian dominance of Indian Ocean trade by circumnavigating Africa and establishing their own trading ports in South Asia. The Ottomans, Casale proposes, were motivated in part by Egypt’s riches, which they needed to support, among other things, their never-ending military rivalry with Safavid Iran. Once in Egypt, however, the Ottomans discovered that the Portuguese had established a blockade of the Red Sea to disrupt Egyptian trade with India and a military outpost at Hormuz to control access to the Persian Gulf. In order to restore trade and income, the Ottomans had to deal with the Portuguese menace and increase the flow of goods and their resulting tax revenue. Over the course of the sixteenth century, this led to the annexation of Yemen and Eritrea in order to enforce a Muslims-only shipping policy in the Red Sea and to prevent the Portuguese from striking at the symbolic heart of the empire, Mecca and Medina, or the imperial shipyards at Suez. Similarly, Basra at the head of the Persian Gulf was incorporated into the empire outright, and Casale documents several negotiated attempts at alliances or outright annexation of territories across the Indian Ocean basin as the Ottoman sphere of influenced waxed and waned over the course of the century.

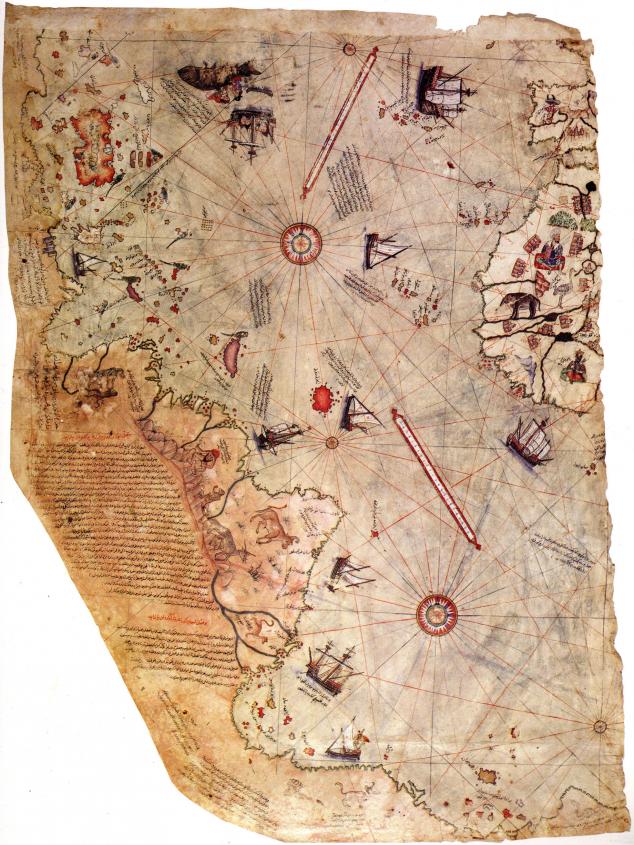

The Ottomans employed a combination of military might, intelligence and espionage, diplomacy, propaganda, science, technology, and cartography in order to counter the Portuguese as they made a serious bid to expand what Casale refers to as a “soft” empire, where trade, rather than political and military power, connected disparate territories across the Indian Ocean, stretching from Yemen and Hormuz to Gujarat, Calicut, and as far as the sultanate of Aceh on the northern tip of Sumatra. Casale suggests that by 1580, the name of the Ottoman Sultan was read out during Friday khutbas from Central Africa to China, their reward for a propaganda campaign against the Portuguese. In telling this story, Casale’s brings us not only the voices of players in Istanbul, Cairo, and Lisbon but also the voices of the Indian and African rulers for the first time as they played these two powers—Ottoman and Portuguese—off of one another in an attempt to secure their dominions.

Casale might exaggerate the originality of his findings and the vision of some of his historical figures but he makes an interesting, readable, and meticulously detailed case for the Ottoman Empire as an active participant in the first century of the Age of Exploration, along with a well-justified explanation for its decision not to pursue expansion at the century’s end. European and World historians alike will find compelling evidence for a new narrative outlining a perilous balance of power in the Indian Ocean during this era in which Europe’s eventual ascendency was not a foregone conclusion. His readers will gain a new appreciation for all of the players involved—not just European and Ottoman, but also the Indian and African rulers who are finally given voice through Casale’s archival work.

Photo Credits:

Fragment of a 1513 Ottoman map depicting the coasts of Western Europe, Northern Africa and Brazil (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

A 1606 map of the Ottoman Empire (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)