By the early autumn of 1862, Americans were reconciled to the fact that the military struggle to determine the fate of the Union was going to be a long and bloody one. Intense fighting was reflected in lengthy casualty lists printed in newspapers, and the names of small towns and rural communities where battles took place became burned into American collective memory: Manassas, Shiloh, Malvern Hill. The grim task of burying fallen soldiers became almost routine as thousands of young men fell in battle and died from illnesses.

Then, on September 17, 1862, the cataclysmic one-day battle of Antietam (or Sharpsburg as the Confederates called it), took the staggering losses to shocking new heights. In a single day of fighting in western Maryland, there were nearly 23,000 casualties, making Antietam the bloodiest day of the entire war. Approximately 3,000 soldiers were killed outright, while thousands more would die in the coming days and weeks or suffer from debilitating injuries for the rest of their lives. In the aftermath, Alexander Gardner toured the battlefield and took a series of photographs. These photographs, the first ever taken of dead American soldiers, shocked the public when they were exhibited in New York.

The sight of bloated corpses lying among the detritus of war brought the carnage to the home front in ways that newspaper reports, casualty lists, and funerals had not. The New York Times wrote of Gardner’s images (mistakenly attributed to Mathew Brady), “If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it…”

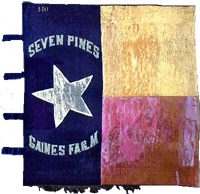

The battle of Antietam held particular significance for Texans. Over a thousand miles from their homes, the Confederate soldiers of Hood’s Texas Brigade would suffer the second-highest casualty rate of any unit during the Civil War. On the morning of September 17, the men of the First, Fourth, and Fifth Texas Infantry regiments were held in reserve and attempting to cook breakfast as the fighting opened. They arrived in the hamlet of Sharpsburg, Maryland at the end of several months of hard campaigning in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Assigned to duty in Virginia early in the war, the Texans earned a reputation for hard fighting after battles at Seven Pines, the Seven Days battles, and the second battle of Manassas. Lee affectionately referred to the men of Hood’s Brigade as “my Texans.” Lee’s army had reversed Confederate fortunes in Virginia, defeating two Federal armies and completely clearing the Commonwealth of Federal forces. Lee’s fateful decision to invade Maryland brought his ragged and outnumbered army to a defensive position in the Maryland countryside opposite George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac.

The Texan’s breakfast was abruptly interrupted when the Federal army launched an assault on the Confederate left flank. Hood’s Brigade fell into formation and marched north, passing wounded and frightened Confederates streaming to the rear. Emerging from the woods in the vicinity of the Dunker Church, named for a German Baptist sect noted for its pacifism, the Texans were ordered forward in a counterattack. The Lone Star soldiers launched a ferocious assault through a cornfield, driving Federal units before them. The attack eventually foundered in the face of intense artillery and musket fire. The Texans stubbornly attempted to move forward, but massive casualties decimated their ranks. Eventually Hood’s Brigade was forced to withdraw under heavy fire. When the Texas Brigade regrouped and counted their losses, it was determined that over 550 of the brigade’s 850 soldiers had been killed, wounded, or captured. The First Texas Infantry, advancing the farthest of any unit in the brigade, suffered a casualty rate of 82% of the 226 men engaged in the battle.  The “Ragged Old First” lost their regimental colors as well. Historian John Cannon reports that when a Federal soldier later in the battle picked them up, he found thirteen Texans lying dead within arm’s reach of the Lone Star flag. The First Texas’ casualty rate at Antietam was the second-highest of the Civil War on either side.

The “Ragged Old First” lost their regimental colors as well. Historian John Cannon reports that when a Federal soldier later in the battle picked them up, he found thirteen Texans lying dead within arm’s reach of the Lone Star flag. The First Texas’ casualty rate at Antietam was the second-highest of the Civil War on either side.

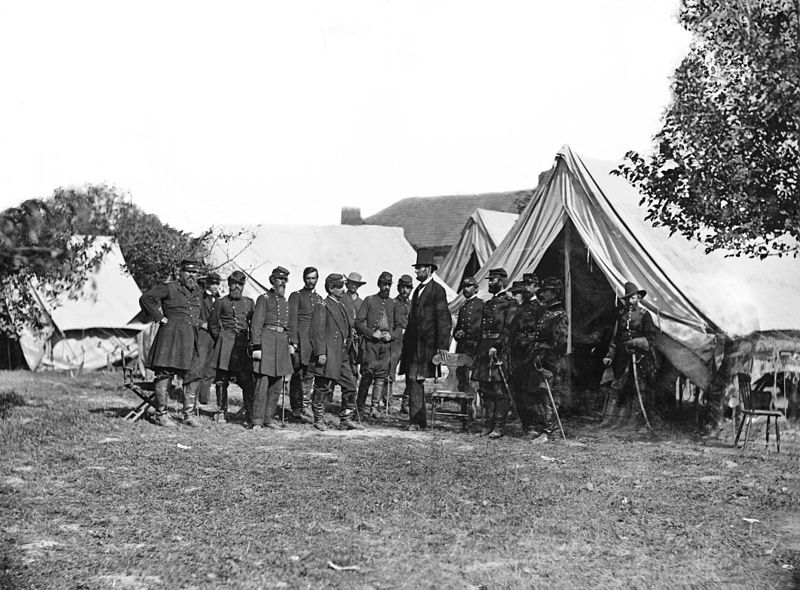

Ultimately, the Texan’s counterattack through the cornfield yielded a pyrrhic tactical victory for Confederate arms. Lee and McClellan clumsily traded blows for the rest of the day, and the Army of Northern Virginia avoided total destruction largely through the timidity of McClellan. The slow moving Federal general allowed Lee’s army to withdraw and declined to aggressively pursue the ragged Confederates. Lincoln, frustrated by McClellan’s blundering and refusal to reengage Lee, eventually removed McClellan from command. McClellan would later run unsuccessfully on the Democratic ticket against Lincoln in the crucial 1864 presidential election.

Lincoln with McClellan after the Battle of Antietam

The battle of Antietam was a critical turning point in the Civil War. Although Union victory was not decisive, Lee’s repulse from Maryland was enough for Lincoln to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. After Antietam the character of the Civil War would change from a limited struggle to preserve the Union to a total war against slavery. The future of thousands of enslaved Texans was therefore directly affected by the fighting in far off Maryland.

Historical documents allow us to see the tragic affect that Antietam and other battles had on individual families in Texas communities during the Civil War. Lieutenant James Waterhouse was killed in action at Antietam. A native of San Augustine, he was the son of wealthy planter and merchant Richard Waterhouse. The 1860 census lists Richard Waterhouse as owning real and personal property totaling $117,300, making him tremendously wealthy for the time. Both Waterhouse sons, Jack and James, served in the First Texas Infantry. Jack transferred from the unit prior to Antietam and appears to have survived the war. James’s death in battle, at age 20, is documented in his service records. The Confederate government later paid Richard Waterhouse $231, the remainder of James’s monthly pay owed him by the army. Tragedy would revisit the Waterhouse’s during the war. In the turmoil of wartime Texas, Richard Waterhouse was murdered and his store robbed on New Year’s Eve, 1863. The case was never solved.

While James Waterhouse’s family remained to mourn his death, Antietam claimed the lives of other young men who are perhaps only remembered in archives. In the 1860 census, Jacob Frank was listed as a 29 year old German immigrant living in Galveston. He was not married and gave his occupation as “Merchant”, although he did not own any property. A young Jewish man seeking opportunity in Texas, Frank joined the First Texas Infantry in the spring of 1862. He likely joined in anticipation of the imminent Conscription Act and to improve his economic and social status. Upon his enlistment in Houston on April 1, 1862, he received a $50 bounty from Confederate recruiting officer Lieutenant W.A. Bedell. On the morning of September 17, Jacob Frank was killed in the cornfield at Antietam. He left no property and no family behind. The American Civil War, staggering in the scope of its destruction, is illuminated through historical documents as the accumulation of thousands of personal tragedies.

You can see Jacob Frank’s $50 bounty certificate here.

All photographs by Alexander Gardner, via Wikimedia Commons

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.