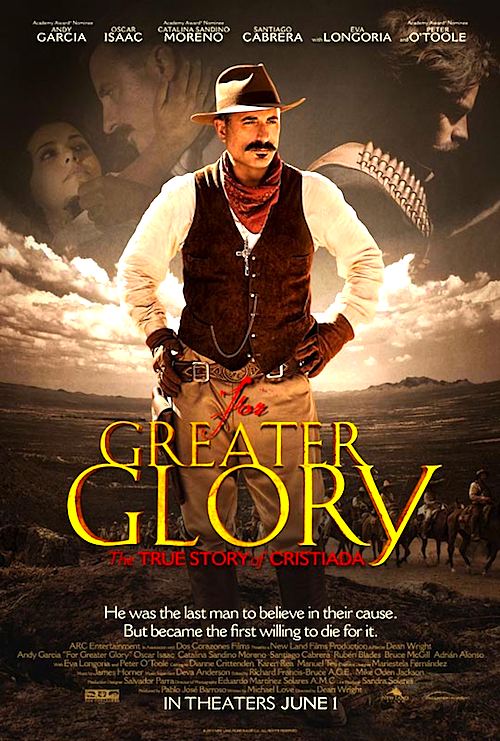

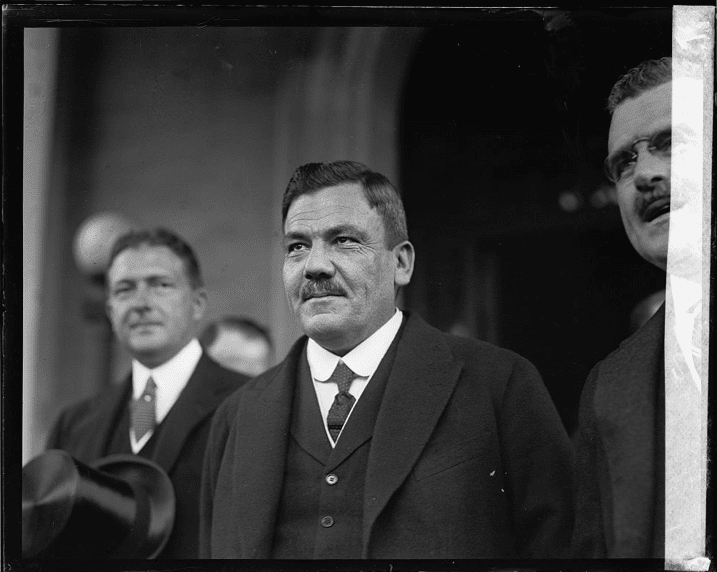

“¡Viva Cristo Rey! Long Live Christ the King!” The rallying cry of the men and women who fought for religious freedom against Mexico’s revolutionary anti-clerical laws gave the movement its name. The Cristero Rebellion (1927-29) was a bloody uprising waged in central and western Mexico less than a decade after the end of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20). Director Dean Wright’s For Greater Glory (opening June 1, 2012) tells the tragic and violent story of President Plutarco Elías Calles’s zealous implementation of the anti-clerical laws inscribed in the 1917 Constitution and popular reactions to it. Tension between the Catholic Church and state had heightened after the Revolution. For liberal politicians—those who favored the modern over tradition—the Church was an outdated institution that threatened their modernist state-building projects. The anti-clerical laws were designed to decrease the Church’s power by, for example, prohibiting it from providing primary education and from intervening in national politics. By 1926, the Church became more vociferous in its opposition to the laws and Calles responded by sending in federal troops to enforce them.

Many reviewers of For Greater Glory will undoubtedly focus on the desire for religious freedom dramatized in the film. Such a view, however, overlooks the film’s other important contributions, not least of which is that it alerts us to the power struggle between two of Mexico’s major institutions. Would the ecclesiastical structure submit to the authority of a secular state or would the Church become a state within a state answering to the Vatican, not the Mexican president? The value of For Greater Glory is that it portrays these concerns and extends beyond them by also offering viewers insight into the impact of religion on daily life in 1920s Mexico, the opposition tactics that cristeros adopted, a history of the conflict, and into how history itself is constructed.

Andy García plays General Enrique Gorostieta Velarde (1889-1929), a retired army general whose military prowess was well-known, but who had retired to a life as a soap manufacturer. As Calles enforces restrictions upon Catholic clergy and public displays of religiosity, Gorostieta clashes with his wife Tula (played by Eva Longoria) over his anti-clerical liberalism and her concern for the Catholic education of their daughters. As Gorostieta’s family adjusts to the changes—Tula becomes responsible for her daughters’ religious education—two other important storylines develop.

The Liga Nacional de Defensa Religiosa (League for the Defense of Religious Liberty) organized opposition to Calles’s law, initially adopting non-violent tactics to fight the restrictions on Catholic life. In response, Calles deployed federal troops to stamp out opposition. Troops desecrate churches, execute priests, and persecute cristeros, both in the film and in real life. It is this violent repression and religious persecution that pushes the League and others to radicalize. The film shows individuals reacting to threats against their civil rights – their right to religious expression – showing how politics and religion came together to drive participation in the Cristero Rebellion. League members take up arms along with 20,000 others, smuggle munitions to the fighters in the field, and form an intelligence network. The League also hires General Gorostieta to unify all of the Cristero armies under one centralized command.

Why was religion so important to Mexicans in this period to propel them into armed revolt? A third storyline that focuses on 13-year-old José Luis Sánchez del Río (who Pope Benedict beatified in 2005), shows the many ways religion saturated daily life. When we meet José, his godfather, Mayor Picazo, is dragging him by the ear to church to apologize to Father Christopher, the local priest, for having misbehaved toward him. José must do penance by cleaning the church. All of this conveys the deference, inculcated at an early age, that the laity had toward the clergy and that underpinned the Church’s authority in early-twentieth-century Mexico. As we watch José complete his penance and begin training as an altar server, we glimpse the central role that religion plays in daily life during this period. Families attend mass together, their homes display religious paintings, and we see children and adults go through the Catholic rites of passage, or the holy sacraments (baptism, communion, marriage, etc.). Seen in this light, the reaction to Calles and repression of the Church becomes much more complex. For some, participation in the rebellion had to do with non-religious concerns and the film shows this. For others, however, civic life was intertwined with religious life and participation in the uprising was as much about defending the civil right to freedom of religious expression as it was about defending markers of one’s identity. After all, Mexicans in 1927 did not go to city hall to get married or to register births and deaths—such major life events were validated by one’s priest and recorded in the local parish record.

The cristeros developed their own reasons for joining the rebellion, but events also occurred at the highest level of national and international politics that they had little chance of influencing. Interspersed among the scenes of Gorostieta readying his army, of League collaborators mobilizing, and of José finding his revolutionary self and suffering for it, is another important story about twentieth-century international relations, especially between Mexico and the United States. While the federales were killing priests and desecrating Catholic churches, the United States saw its economic and political interests in Mexico threatened. In one scene, President Calvin Coolidge sends Ambassador Dwight Whitney Morrow to Mexico to negotiate a resolution to the war that will protect U.S. oil interests. In exchange for oil concessions, the U.S. decides to sell military weaponry to the Mexican government. Not unsurprisingly, Ambassador Morrow becomes a key figure in peace talks, not between the state and cristeros, but between the state and the Church, the two institutions who were fighting for legitimacy and hegemony. In the film, all of this happens without cristero input. In fact, while Calles and Morrow discuss an end to the conflict that would protect U.S. interests and appease American members of the Knights of Columbus who pressured the State Department into acting on behalf of their besieged Mexican Catholic brethren, Gorostieta is busy building a unified cristero army out of many smaller militant groups. Unbeknownst to him and the other cristero generals, many of whom had fought in the Revolution, the stakes and tactics of war had changed. What began as a local conflict would be shaped by Cold War geopolitics, new military technologies, and a new mode of governmentality embodied by the political party that would rule Mexico for 70 years, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party, PRI).

This film is, superficially, a descendant of spaghetti western kitsch with all of the expected gunfights and feats of bravado, but upon closer analysis, it offers much more than that. It is about war and new methods of communication. Railroads, telegraphs, and photographic images made possible greater global integration, inasmuch as information about the cristeros spread around the globe more rapidly. The film also provides viewers with an entertaining lesson in the sources that historians use to construct narratives of the past. In this case, Gorostieta’s letters to his wife, photographs, presidential speeches, and records of diplomatic intervention provide the primary sources of a narrative that shows elite perceptions of the cristeros and ordinary peoples’ own perceptions of themselves and their role in national and regional politics. Finally, For Greater Glory offers an explanation for why people radicalize in response to government action, reminding viewers that war is never simple.

The Cristero Rebellion inspires homage and this film is dedicated to those who fought and died in the rebellion, yet there are a few surprising holes. Gorostieta says in one scene that “women are as important to this war as any soldier” yet the lone female figure shown collaborating with the League plays a minor role in the larger narrative and the range of female cristero activity shown in the film is limited to the collection of signatures in petition drives and smuggling bullets. Women from all social classes acted as cristeros or as their supporters in a wide range of ways. Notwithstanding, For Greater Glory is a moving and informative film and deserves a wide audience.

For more on the church-state crisis of the post-revolutionary period in Mexico you might enjoy:

Matthew Butler, Popular Piety and Political Identity in Mexico’s Cristero Rebellion: Michoacán, 1927-29 (2004)

And here on NEP: Matthew Butler’s review of Graham Greene’s novel, The Power and the Glory, which takes place during the same period.

Watch “For Greater Glory” here.

Photo credits:

National Photo Company, “Gen. P.E. Calles,” 31 October, 1924

National Photo Company via The Library of Congress

Unknown photographer, Untitled

Unknown photographer via locaburg/Flickr Creative Commons