I wrote about Ulysses Grant for two reasons: necessity and curiosity. The necessity was that I needed a major American figure whose life and career covered the middle of the nineteenth century. Seventeen years ago I embarked on a project to write the history of the United States in the form of several biographies. The biographies would be of important people whose lives in some way or other captured the central issues of their times. I wrote about Benjamin Franklin, who exemplified the eighteenth-century struggle of Americans to redefine themselves not as British subjects but as citizens of an independent American republic. I wrote about Andrew Jackson as the herald of American democracy: the People’s President who helped put the country on the path to broad participation in governance. I wrote about Theodore Roosevelt as the leader who grappled with the issues raised by industrialization and America’s rise to world power. I wrote about Franklin Roosevelt and the Great Depression and World War II.

But I had a gap in the nineteenth century—a very large gap that included the sectional crisis and the Civil War. I considered writing about Abraham Lincoln, but at the time I was doing the considering, Lincoln was celebrating (posthumously of course) his bicentennial, and books on Lincoln were pouring off the presses. Besides, my gap stretched from the death of Andrew Jackson in 1845 until Theodore Roosevelt became an adult in the early 1880s. (My biographies overlap one another in this regard; babies and children don’t engage much in the public events of their times.) Lincoln was assassinated in 1865; if I wrote about him, I’d have to write a separate volume to get me up to the 1880s.

So I settled on Ulysses Grant. His dates were perfect. He was 23 when Jackson died, and he lived until 1885. He was involved in the big events of his lifetime: the war with Mexico, the sectional crisis, the Civil War and Reconstruction. One book, on Grant, and my nineteenth-century gap would be filled.

Here’s where the curiosity kicked in. I had written about presidents before, but I had never written about anyone who was most famous for being a soldier. (Jackson became famous for being a soldier, but he is better known as a president.) I have been intrigued by soldiers—by warriors—because, for better and worse, they have very often been the drivers of history. No society (that I have ever come across) has existed without war. Every society celebrates its warriors—and no society more than America, which makes its warrior-heroes president and honors even those who merely put on the military uniform.

Related to my curiosity about warriors is the larger question of war. Specifically: why is war so common? Americans consider ourselves a peace-loving people, but in the past two centuries no country has gone to war (declared and undeclared) more often than the United States. And it’s not just Americans. Every society does it. Why is this? Most people think war is a bad thing, better off avoided. But people go to war again and again and again. Why?

I thought I might gain some insight by looking at Ulysses Grant. Grant was one of a type common in history: a man who was good at war but at little else. He performed ably and bravely during the war with Mexico as a young man, but during the 1850s he floundered. He left the army because there were no wars to fight, and he couldn’t find his footing in civilian life. He failed as a farmer, as a businessman, at just about everything. He was reconciled to a life of persistent mediocrity when the Civil War came and rescued him. He reenlisted and rocketed to the top of the Union chain of command.

Why? Because he had a singular gift for war. Others in the Civil War—Robert E. Lee, William Sherman, Phil Sheridan, Stonewall Jackson, to name the most conspicuous—shared the gift. War brought out the best in each of them. War provided the singular focus civilian life often lacked. War made things very simple: you lived or you died, you won or you lost. Grant and the others blossomed under war’s harsh but straightforward demands.

Grant more than the others. The traits that yield success in war are at once admirable and appalling. Grant was physically fearless, never worrying about whether the next shell would take his head off. And he had the ability—this is the appalling part—to send thousands of men to their deaths. Lincoln’s other generals couldn’t do it. Grant could. Convinced that preserving the Union would save millions of lives in the future, Grant was willing to sacrifice thousands in the present.

Americans (in the North, that is) loved him for it. He was the great hero of the age. His countrymen made him president, twice (he could have been elected a third and fourth time if he wanted, but he declined). Grant’s presidency has long been underrated. This is largely because his enemies wrote the histories and because Reconstruction was the most challenging time in American history to be president. Surrounded by the self-seeking and corruption of the Gilded Age, Grant nonetheless brought an essential humanity to the White House. He tried to give the Indian tribes a belated fair break, and he strove mightily to ensure that African Americans received the civil rights and equal treatment they were supposedly accorded by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. He didn’t accomplish all he fought for: the overwhelming weight of public opinion was against him. But the Indians, who would have been exterminated if the matter had been left to some of Grant’s contemporaries, survived. And the Ku Klux Klan was shattered in the South by Grant’s bold and timely action. (It would, unfortunately, revive in the twentieth century.)

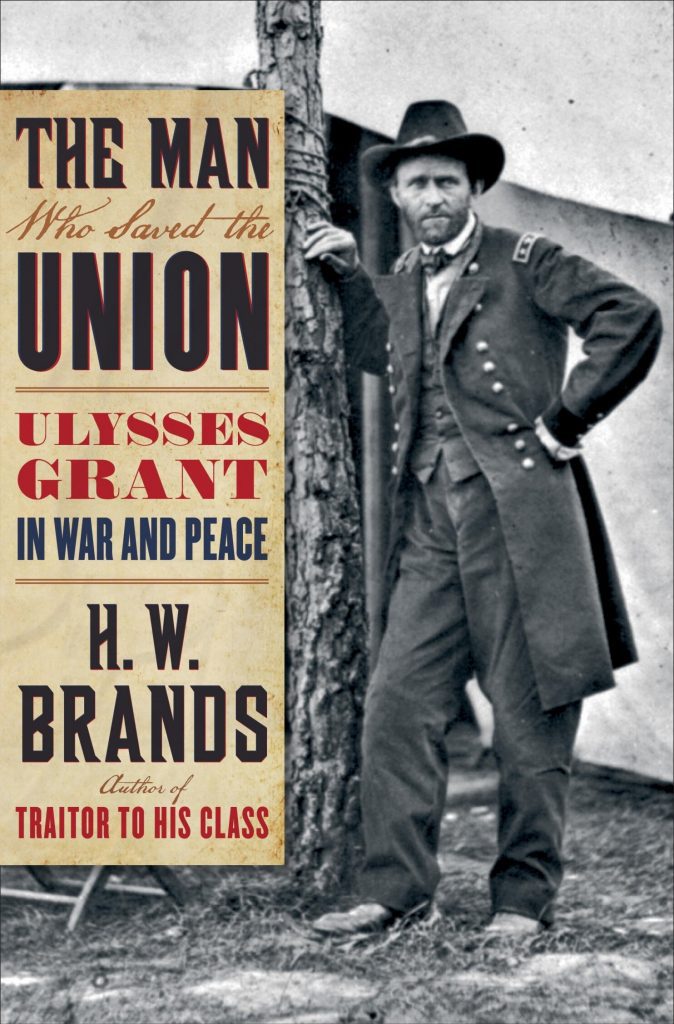

I called my book The Man Who Saved the Union, because Grant did just that. Once during the Civil War, again during Reconstruction. Pretty remarkable, considering how little promise he showed before war gave him his chance.

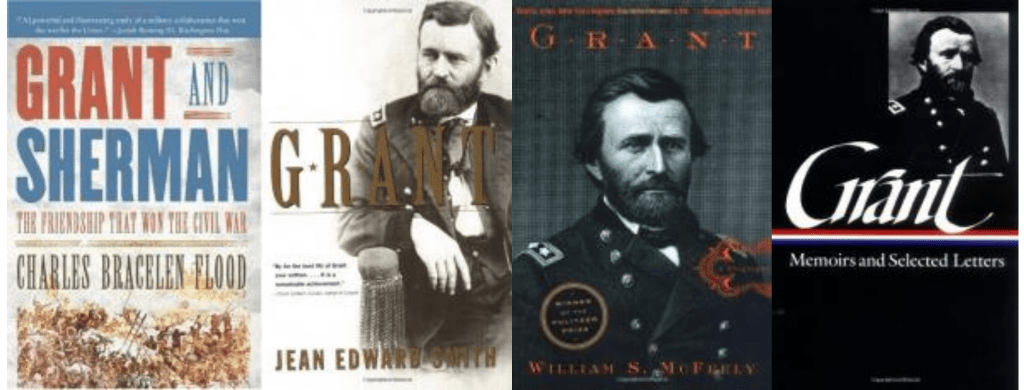

Ulysses S. Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters (1990).

The greatest memoir by a former president, largely because it doesn’t touch his presidency. This is a history of the Civil War as told by the victor. Universally acclaimed as one of the best military memoirs ever written.

William S. McFeely, Grant (1981).

Still the starting point for studying Grant. McFeeley takes him seriously as a general, which everyone does, but also as president, which many historians before him did not. Nonetheless, McFeeley considers his presidency dismal. This biography employs more psychoanalysis, which was in vogue among historians at the time of the writing than is common today.

Jean Edward Smith, Grant (2001).

Solid, respectful, comprehensive. Smith is less opinionated than McFeely and consequently less entertaining or less infuriating, depending on the reader’s point of view.

Charles B. Flood, Grant and Sherman (2005).

The subtitle is “The Friendship that Won the Civil War,” a characterization that is not far wrong. Provides further insight into the warrior mentality.

Photo Credits:

Mathew Brady, General Ulysses S. Grant, Cold Harbor, VA, US National Archives; George P.A. Healy, The Peacemakers, Wikimedia