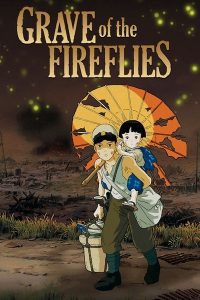

Grave of the Fireflies (1988) is an uncompromising critique of Japanese society in the waning months of World War II, and a major milestone in the development of one of the world’s foremost animation studios.

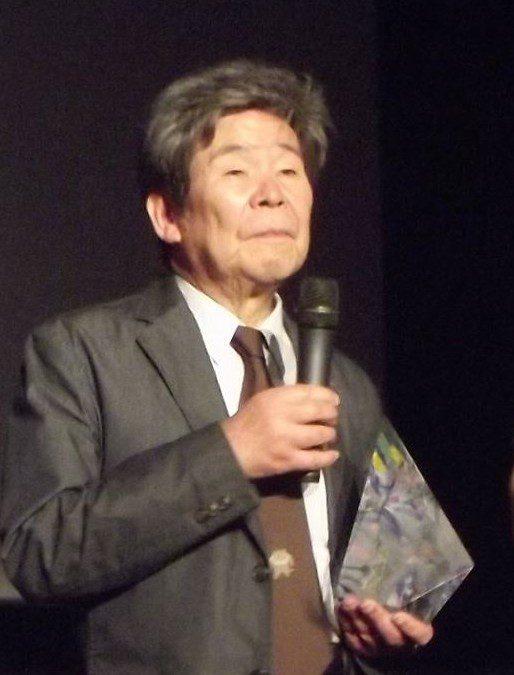

1988 was a year of firsts for the young Studio Ghibli. In that year the studio’s creative leader, Hayao Miyazaki, directed My Neighbor Totoro, his first film set in historical Japan rather than in a fantasy world. The studio did not expect Totoro to be a financial success, so it decided to package it with an adaptation of a wartime melodramatic novel titled Hotaru no Haka, or Grave of the Fireflies. Fireflies was the first Ghibli film neither written nor directed by Miyazaki. Instead it was helmed by longtime animator Isao Takahata, who would go on to direct several more adult-oriented anime for Ghibli.

The studio’s expectations proved correct in the short term, but when Totoro aired on television it found its audience and became Ghibli’s first breakout hit. It is known and loved internationally and its title character is now the studio’s iconic mascot. Fireflies, meanwhile, is something of an anomaly. Though well-known to anime fans and highly esteemed by critics, it is one of the only Ghibli titles for which Disney is not the overseas distributor. Its DVD and Blu-Ray releases are of dubious quality, and it has been subjected to two different English language dubs despite the fact that, as a movie for adults, watching it in a language other than Japanese is as ridiculous as watching a dubbed Kurosawa or Ozu film. Subtitles better preserve the original characterizations and meanings.

But the most substantial distinctions between Fireflies and the rest of the Ghibli canon are its pessimistic message and its morally-compromised characters. As brilliant as Miyazaki’s renowned fantasies, Takahata’s later stories, and other Ghibli directors’ works are (and they almost always are) typically characterized by good people working hard toward clear-cut and laudable objectives. Not so with Fireflies. Its protagonists, a boy named Seita and his young sister Setsuko, are almost true-to-life. They think irrationally, make bad decisions, and behave in ways movie good guys usually don’t.

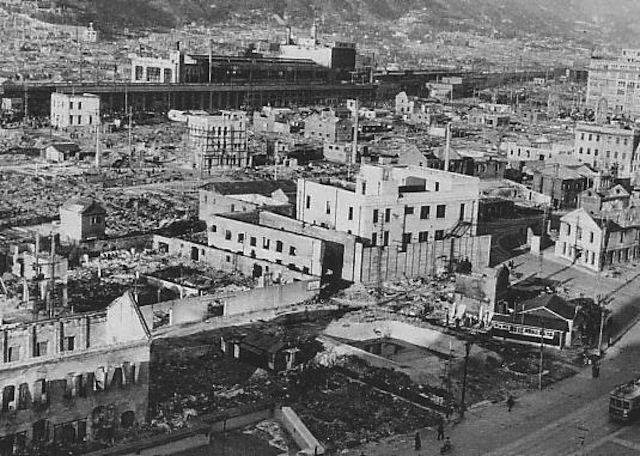

This is particularly true of Seita. As the older sibling, he is responsible for the care of his sister when their mother dies in a firebombing raid that destroys their house and their father is killed in battle. At first he does well. He finds lodging for himself and Setsuko in the home of a woman who provides them with food in exchange for their mother’s clothes. This woman embodies the attitude that, in wartime, everyone must make sacrifices for the good of the nation. The best touches of visual detail in the movie are when she is seen scraping burnt leavings from the bottom of a cooking vessel, and when her young lodgers carefully eat every grain of rationed rice and each infinitesimally small crumb of candy in their possession.

Seita begins to go astray, both from his duties as a caregiver and from his social duties, when he quarrels with the woman and leaves the comparative comfort of her house. At about 14 he is old enough to work, to “contribute to the war effort” as the woman commands him to do, but he opts not to seek employment with a munitions factory or a work detail. He never articulates his reason, but it is not anti-war sentiment. Seita is as emotionally invested in the success of Japan’s imperial mission as are all of the adults he knows. Rather, he seems to be motivated by a vainglorious search for individual autonomy. Generally speaking, this is not a commendable impulse in Japanese culture, especially not during the war.

Seita takes Setsuko to an abandoned bomb shelter near a small lake outside of town. In his mind, and at first glance, this appears to be an idyllic retreat from the horrors of the war. They spend their first night there catching fireflies, delicate creatures that live a lifespan of mere days before winking out of existence. The symbolism is obvious, but it is also the occasion for the movie’s most beautiful and haunting images.

It is not long, though, before it becomes clear that Seita is unequipped to handle life in exile. Setsuko develops a rash that grows increasingly painful, and she begins to exhibit the disturbing physical symptoms of malnourishment. Though Seita has some money in a bank account, he turns to stealing food, a serious crime particularly during wartime. Perhaps unconsciously, in his orphanhood he has become stubbornly obsessed with living outside of society. The death of the four-year-old Setsuko is therefore inevitable, and Seita himself, we have learned at the beginning of the movie, will die homeless and starving shortly after Japan’s surrender.

The movie is a cautionary tale about young people who recklessly buck social mores, but Seita is not portrayed as solely responsible for his and Setsuko’s deaths. In fact, he hardly seems to realize what he is doing or what is happening to them. He is a child, well-intentioned but confused and psychologically shattered. The movie reserves its moral censure for the adult characters. Director Takahata, who also wrote the screenplay, shows adults to be willfully apathetic about the children’s desperate plight. The woman who takes them in (and takes their mother’s possessions as payment) also drives them out with harsh criticism and justifies it as an act of patriotism. A doctor diagnoses Setsuko with malnutrition, but refuses to give her medicine and sends her and Seita away with no food and no advice. The worker who discovers Seita’s body among other homeless dead in the movie’s prologue seems to be unmoved, poking the corpses and searching their possessions before casting them aside. Only a police officer shows Seita some kindness by declining to press charges for theft, but in Seita’s case it might have been a greater kindness to take him into custody. Takahata has said that Fireflies is not an anti-war film, as many of Miyazaki’s movies quite clearly are, but it is certainly a bleak portrayal of the material and social condition Japan was in at the end of its last great war.

Fireflies is not my favorite Ghibli movie (several of Miyazaki’s fantasy pieces vie for that position with Yoshifumi Kondo’s 1995 rumination on creativity Whisper of the Heart). Nor is it my favorite movie by Takahata (that’s 1991’s Only Yesterday). Arguably, Hayao’s son Goro Miyazaki’s subtle treatment of Japan’s postwar economic boom make From Up on Poppy Hill (2011) a better historical movie than Fireflies. The source material for Fireflies is just a touch too melodramatic, and its world does not leap from the screen and grip the imagination the way other Ghibli movies do. Yet as a work of art and a piece of historical fiction set during an especially difficult era, it is undeniably a valuable achievement. Embracing Defeat, John Dower’s 1999 Pulitzer-winning nonfiction book about early postwar Japanese culture, would make an excellent pairing with Grave of the Fireflies. The movie also stands on its own, and as an early herald of Studio Ghibli’s emergence as a leader in sophisticated animated entertainment.