by Rachel Ozanne

In the past ten years, Americans have shown a sustained interest in cultural depictions of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), or the Mormon Church. South Park’s 2003 episode “All about Mormons” and the 2011 musical The Book of Mormon satirized the founding of the LDS church. Other television shows, however, like HBO’s Big Love and TLC’s Sister Wives have tried to portray other non-LDS strands of Mormonism in a more complex way by exploring modern day polygamy. Now with Mitt Romney’s nomination for the Republican Party candidate for President, the Mormon faith once again finds itself in the spotlight.

With all the drama of television, or quite frankly a presidential campaign, the historical origins of Mormonism can get lost in the shuffle. Despite all the media coverage, a religion that some scholars have deemed the quintessential American religion remains largely misunderstood by the American public. For those interested in learning more, however, about many of the fundamental doctrines and the beginnings of the Mormon (and particularly LDS) Church, I recommend Richard L. Bushman’s recent biography of Mormonism’s founder Joseph Smith, Jr., Rough Stone Rolling.

With all the drama of television, or quite frankly a presidential campaign, the historical origins of Mormonism can get lost in the shuffle. Despite all the media coverage, a religion that some scholars have deemed the quintessential American religion remains largely misunderstood by the American public. For those interested in learning more, however, about many of the fundamental doctrines and the beginnings of the Mormon (and particularly LDS) Church, I recommend Richard L. Bushman’s recent biography of Mormonism’s founder Joseph Smith, Jr., Rough Stone Rolling.

In Rough Stone Rolling, Bushman brings his extensive knowledge of early Mormon history to expand upon his first book about the life of Joseph Smith, Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism, by tracing the entirety of Smith’s life from the cradle to the grave with a special emphasis on the cultural context out of which he came. Bushman himself is a member of the LDS Church, but his pro-Mormon bias does not prevent him from presenting Smith as a flawed human being, noting that Smith never set himself up as a perfect moral exemplar, but rather a “rough stone rolling”—one that would be smoothed over in time.

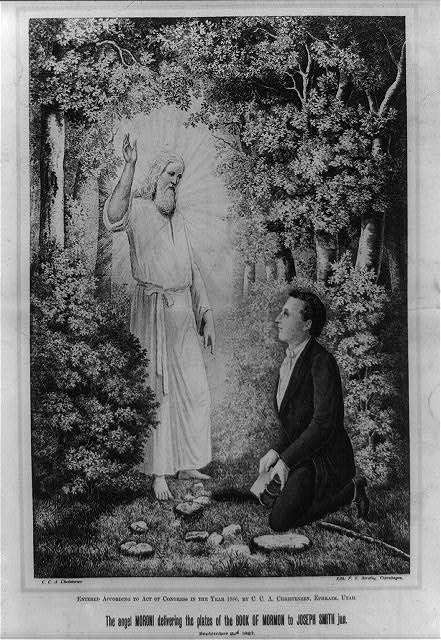

“The angel Moroni delivering the plates of the Book of Mormon to Joseph Smith jun.” 1886 print (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

“The angel Moroni delivering the plates of the Book of Mormon to Joseph Smith jun.” 1886 print (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

Bushman’s approach to writing a biography of Joseph Smith almost necessarily focuses heavily on Smith’s spiritual development and how it went hand in hand with the development of Mormonism. Thus, the narrative of the book is punctuated by major events of Smith’s spiritual life, well known to followers of Joseph Smith: his first contact with the Angel Moroni; his discovery of the golden plates on which the Book of Mormon was written; the transcription of those plates into an English text; the restoration of the Aaronic priesthood and the priesthood of Melchizedek in 1829; the founding of the church in 1830; and various revelations that instituted new doctrine or prompted the growing Mormon church to move from New York to Ohio and eventually to Illinois, where Smith was killed.

However, Bushman also spends much time providing the cultural and political context of Smith’s life. In so doing, he implicitly engages with a number of debates about Mormon history. For instance, did Joseph Smith invent the Book of Mormon or was he truly divinely inspired? Was he a power hungry man who had “convenient” revelations resting the sole power of revelation for the LDS church in him or did he really hear commands from God?

Bushman’s treatment of polygamy is particularly engaging, given that mainstream Mormonism (the LDS Church) officially gave up polygamy in 1890. Even though Bushman doesn’t support polygamy himself, he tries to explain why “plural marriage” (the Mormon term for polygamy) made sense in the context of Joseph Smith’s theology. In particular, Bushman claims that Smith emphasized the importance of family, so he created, or was inspired to create, rituals to ensure that marriage and family lasted for eternity—marriage sealing and baptism for the dead, for instance. In this light, taking on multiple wives was considered another way to extend the family and preserve as many people together in the afterlife as possible.

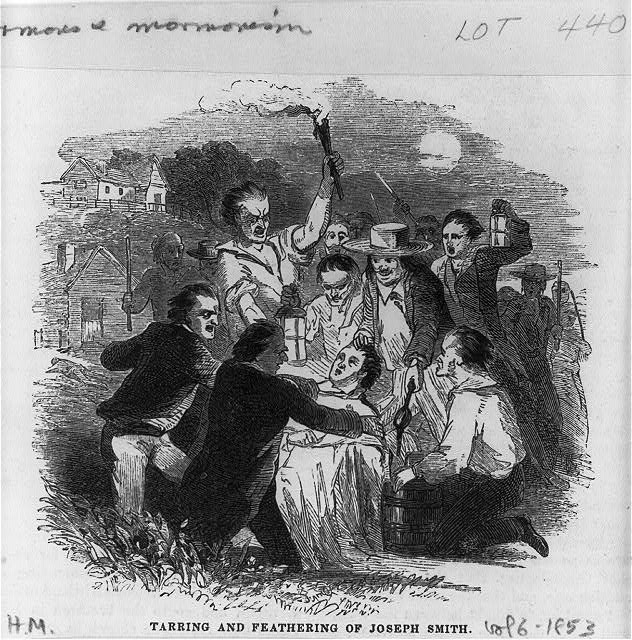

1853 Harpers Magazine engraving of Smith being tarred and feathered (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

1853 Harpers Magazine engraving of Smith being tarred and feathered (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

Perhaps it is unsurprising that he takes a sympathetic view of polygamy, because he views Smith sympathetically throughout the book. Skeptics may find his matter-of-fact dealings with angels and revelations a bit hard to swallow, and strong opponents of polygamy will not likely be satisfied with Bushman’s assessment that plural marriage was mostly a loving institution at its beginning. It is important to remember, however, that Smith was not the only antebellum American experimenting with different kinds of marriage or claiming to receive messages directly from God. He was in good company with the Oneida Community, Ellen G. White and the Seventh-day Adventists, and many other 19th-century religious groups.

The Book of Mormon Broadway musical, New York City, 2011 (Image courtesy of Brechtbug/Flickr Creative Commons)

As a biography of Joseph Smith, Rough Stone Rolling only tracks the development of the Church of Latter-day Saints up to Smith’s death in 1844 at the hands of some angry Illinois citizens. Readers interested in the rest of the story will have to pick up other books to learn about schisms in the early church; the trek westward of the followers of Brigham Young; the contest between Mormons and the U.S. government over the legality of polygamy; and the history of race and Mormonism. Nevertheless, Bushman’s history provides great insight for a reader trying to understand the appeal of Joseph Smith and the Mormon faith from the outside.