Thirty five years ago today, Iraq’s President Saddam Hussein made a dangerous gamble that did not pay off: with Iran vulnerable after the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Hussein attacked the oil-rich province of Khuzistan, inhabited mostly by Arabs. Since its independence in 1932, Iraq was critical of the Pahlavi monarchy for fashioning Iran as a Persian nation, and had disputed Iran’s right to a province so heavily populated by Arabs. Hussein’s early successes on the warfront compelled Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s new leader, to deploy an enormous number of recently, and often poorly, trained soldiers to the front. By 1982, Khomeini had forced Hussein’s hand. Retreating to the internationally recognized borders, Iraq’s President offered Khomeini peace. An emboldened Khomeini went on the offensive. The war reached a fever pitch in 1986 when Iran overtook Iraq’s al-Faw Peninsula. Western governments, until then satisfied with funding both sides, stepped in to resolve the conflict, which finally ended in 1988.

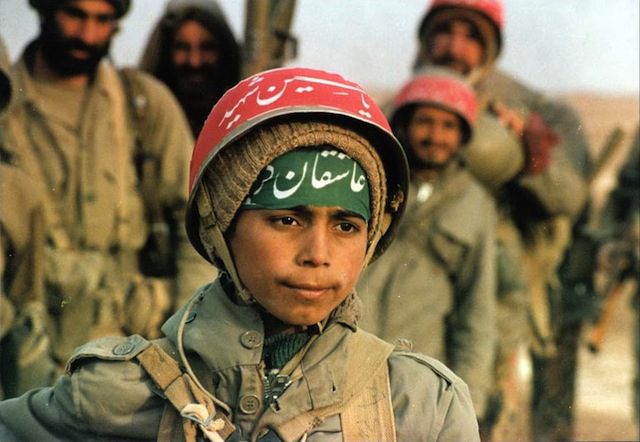

The Iran-Iraq War (1980-88), largely overshadowed in the United States by Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, cost roughly one million lives. While Iran drew the attention of the West to Hussein’s illegal use of chemical weapons, Iraq paraded before the international press Iranian child soldiers (under the age of fifteen), who constituted a staggering 100,000 of Iran’s casualties. Hussein and Khomeini, both egregious violators of human rights, caused Iranians and Iraqis tremendous trauma.

A few scholars in the West, most notably Dina Khoury, Amatzia Baram, and Hamid Dabashi, have seriously contended with the effects of the devastating total war. Most historians have instead emphasized the political revolutions that shaped the two nations. For Iraqi studies, much ink has been spilt on Abd al-Karim Qasim’s Republican Revolution of 1958 and the Bathist coup led by Hasan al-Bakr and Saddam Hussein in 1968. Iran too has had its important political upheavals, including the CIA-backed 1953 coup that ousted democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh as well as the 1979 Islamic Revolution that finally resulted in the end of monarchy, and the rise of a fundamentalist Shi‘i government, in Iran. Other scholars and commentators are concerned with the pressing questions of today’s Middle East. As Iraq now falls apart along ethnic and religious lines after over a decade of US intervention and Iran emerges from decades of painful sanctions, many rightfully preoccupy themselves with lamenting or celebrating present circumstances.

The Iran-Iraq War, however, serves as both a portent for the violence that awaited Iraq in the coming decades and as evidence that Iraq did not have to collapse as it so tragically has. It could have arguably survived its colonial foundation. The French and the British had, after all, invented a country, causing many today to dismiss Iraq’s territorial integrity. One might be compelled to agree with the pessimistic forecasts of political analysts, especially as violence continues to grip Iraq. The Iran-Iraq War, however, demonstrates the legitimacy of these questionably drawn borders.

Iraq’s invasion of Khuzistan, premised on Iran’s illegitimate claim to Arab populations, failed to resonate with Iranian Arabs. Not only that, Iran’s bid for the hearts and minds of Iraq’s Shi‘a also failed. The idea that people would prefer to belong to nation-states that reflected their ethnic makeup or religious values proved incorrect. In fact, it was the support of the Shi‘a for the Iraqi state and the Arabs for the Islamic Republic that gave credibility to territorial boundaries. No longer could the Iranian and Iraqi states speak of their national borders as the result of malicious colonialists drawing lines to maximize conflict: the people had spoken and they had supported their nations.

Iraqi soldiers celebrate after recapturing the Faw Peninsula in Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War. Behind them is a bullet-ridden portrait of Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

That Iraq should fall apart as it has was not an inevitable result of post-colonial borders; it was the result of the American invasion in 2003. Shi‘i and Sunni Iraqis believed in the nation-state project, they fought alongside each other to defend their nation during a bloody eight-year battle with Iran, and now they flee together from Iraq with Syrian refugees as their nation, and state, collapses. Iranian political influence, though negligible during the Iran-Iraq War, has now consumed Iraqi society, resulting in heightened suspicion of Iraqi Shi‘a. Although the Bath Party expelled over 300,000 Iraqis, assumed to be of Iranian heritage during its rule, the fear among Sunnis of widespread Shi‘i loyalty to Iran runs deep. Largely due to the poor governance and eventual ousting of Iranian-backed Iraqi President Nouri al-Maliki, ISIS has captured the support of Sunnis and former Bathists, who were alienated from government since the American invasion of 2003. This, has resulted in the mass murder, rape, and exile of Iraq’s Shi‘a and the disintegration of the country.

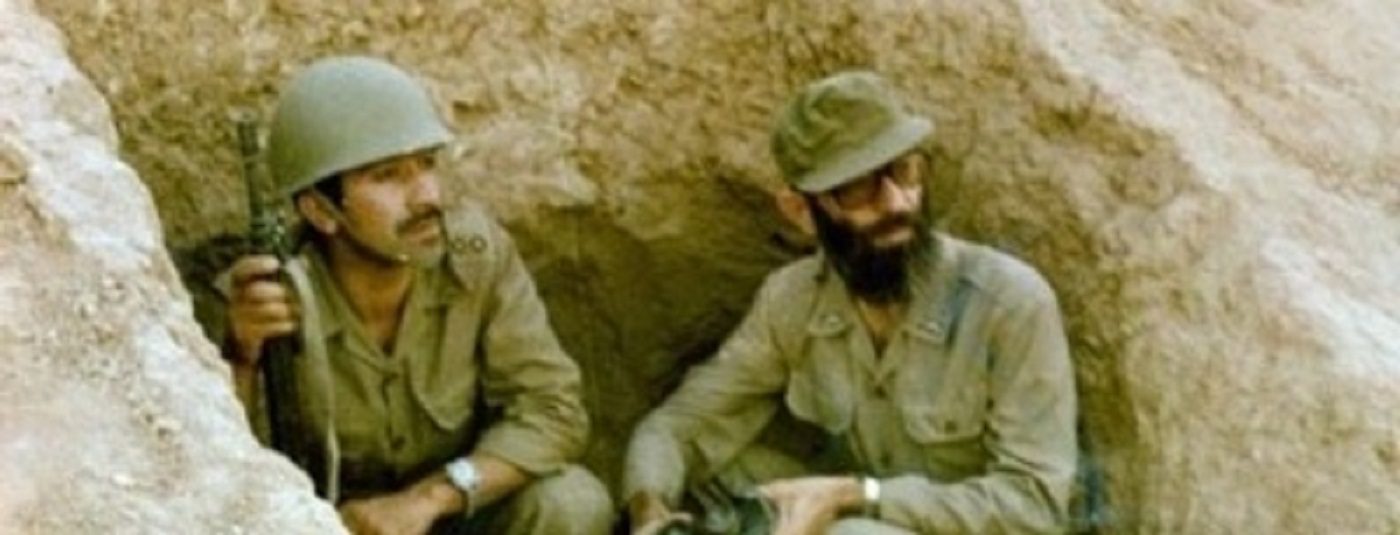

Ali Khamenei (right), the future Supreme Leader of Iran, in a trench during the Iran-Iraq war. Via Wikipedia

Not only does the Iran-Iraq War demonstrate the lost possibility of Iraqi unity, but it was also a harbinger of the region’s fraught future. Students and observers of today’s Middle East must study the war in order to understand the nature of violence in Iraq, a country that has struggled with horrific violence since its founding; Iranian influence in Iraq, which international actors, especially the United States, unwittingly strengthened by causing humanitarian crises; human exchange between multiple nations, where travel across porous boundaries caused dangerous conflict; and the role of the international community in the Middle East, as human rights organizations, journalists, and state actors all presented, and contributed to, the Middle East in ways quite familiar to us today.

The bloodshed in Iraq never did end. Many Iraqis describe living in a war zone or in poverty due to crippling sanctions practically their entire lives, beginning in the 1980s. When Hussein invaded Khuzistan, thirty-five years ago today, he provoked a war that would test the loyalties of Iraq’s Shi’a and Iran’s Arabs. Both communities fought alongside their compatriots in order to protect their nations. As we witness ISIS tear the nation apart by fomenting and exploiting sectarian discord, studies of the Iran-Iraq War allow us to appreciate how far Iraq has strayed from earlier Shi‘i-Sunni unity. Neither medieval disputes nor colonial history may bear the full burden of responsibility for causing sectarian violence; it took the intervention of several powerful countries, including our own, over the course of several decades to finally divide Iraq so deeply along ethnic and religious lines.