by David A. Conrad

Writers of ethnically-themed novels are often pegged as simply recording their family stories. However, by the time National Book Award finalist Julie Otsuka set out to capture her mother’s stories of “camp,” dementia had already stolen her once-clear memories. For the novel that became When the Emperor was Divine, Otsuka had to research the events that took her, as a 10-year-old along with 120,000 other Japanese Americans, from their homes on the west coast designated them as “enemy aliens,” and confined them to internment camps in inland desert areas during World War II. Her research produced the moving and telling details that reveal the profound loss of fought-for home and identity, the crushing helplessness, and resulting mental incapacity, that beset Japanese Americans with the onset of the war. Her novel conveys how they were literally stripped of all but what they could carry, and forced them to wait for the end of the war imprisoned in temporary barracks behind barbed wire removed from the stabilizing routines of work, school, home, community, and greater acceptance. Inspired by Hemingway, Otsuka uses luminous prose to convey the unmooring of one Japanese American family though everyday objects: the family dog that had to be killed because it could not be brought or adopted, a jump rope cut into pieces, stones thrown through train windows, silverware buried in the garden. A painter by training, Otsuka states that When the Emperor was Divine first came to her in images, which she then set down in words (Texas Book Festival, Oct. 27, 2012).

In contrast, Otsuka’s second novel, The Buddha in the Attic, for which she won the PEN/Faulkner Award, flowed as a multitude of “chanting” voices. Based upon two years of research into the lives of Japanese picture brides—young Japanese women of Otsuka’s grandmother’s generation, who followed arranged marriages and came to America between 1908 and 1924 only to find that neither their husbands nor their circumstances matched their advertised claims. Otsuka uses a “we” voice with no single protagonist to evoke the range of struggles and adaptions women made when they entered hard, working-class lives alongside their husbands on farms, in stores and restaurants, boarding houses, mining and lumbering towns, raising children and keeping house, sometimes in tents or newly built shacks without electricity or running water. There are few documents recorded in these women’s own voices and Otsuka recreates their world through their eyes. It is not a glorious story of immigrant integration and success, but a richly layered and compelling account of struggle and survival that honors the picture brides’ humanity while underscoring that their ranks did not produce any recognized heroes or literary tropes.

In contrast, Otsuka’s second novel, The Buddha in the Attic, for which she won the PEN/Faulkner Award, flowed as a multitude of “chanting” voices. Based upon two years of research into the lives of Japanese picture brides—young Japanese women of Otsuka’s grandmother’s generation, who followed arranged marriages and came to America between 1908 and 1924 only to find that neither their husbands nor their circumstances matched their advertised claims. Otsuka uses a “we” voice with no single protagonist to evoke the range of struggles and adaptions women made when they entered hard, working-class lives alongside their husbands on farms, in stores and restaurants, boarding houses, mining and lumbering towns, raising children and keeping house, sometimes in tents or newly built shacks without electricity or running water. There are few documents recorded in these women’s own voices and Otsuka recreates their world through their eyes. It is not a glorious story of immigrant integration and success, but a richly layered and compelling account of struggle and survival that honors the picture brides’ humanity while underscoring that their ranks did not produce any recognized heroes or literary tropes.

Japanese-Americans boarding a train in Los Angeles bound for an internment camp, April 1942 (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

Japanese-Americans standing by posters with internment orders (Image courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior)

These two slight novels are well worth the couple of hours that they take to consume. Otsuka uses elegant and compact prose to transport readers to a transient time and set of circumstances that are, thankfully, long over, although the psychic remnants continue to resonate.

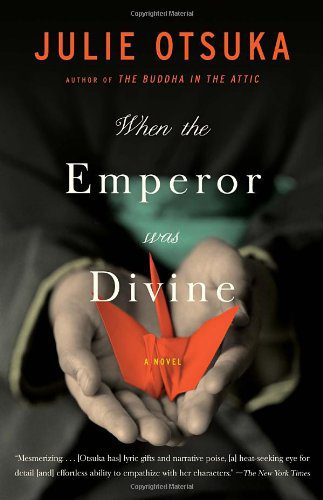

You can purchase When the Emperor Was Divine on Amazon here.

You may also like:

David A. Conrad’s reviews of Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II and Shinohata: A Portrait of a Japanese Village