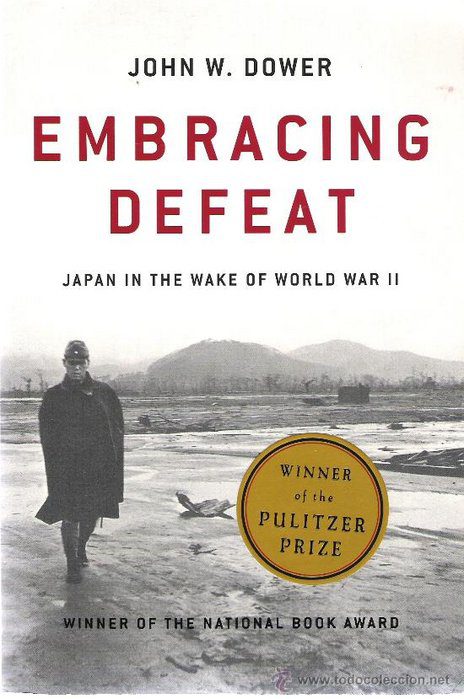

Before John Dower’s Embracing Defeat, many English-language accounts of the United States’ occupation of Japan contextualized the event in terms of American foreign policy and the emerging Cold War. Scholars writing from this Western-centric perspective produced much fine scholarship, and no doubt will continue to do so. But Embracing Defeat shifted the discussion from a debate over American motives to an analysis of the Japanese experience, and in doing so won critical acclaim and popular success. This Pulitzer Prize-winning tome reveals to Western audiences what many in Japan have long understood: that the American occupation was, in many ways, the most transformative event in modern Japanese history.

Dower sets out to convey “some sense of the Japanese experience of defeat by focusing on social and cultural developments. . . at all levels of society.” Initially, the bitter reality that their exhausting war had ended in defeat proved profoundly demoralizing for many Japanese citizens. Dower’s portrayal of the shantytowns of bombed-out Tokyo provides poignant evidence of the impoverished condition in which many Japanese found themselves at war’s end. But as Japan embarked on its long occupation interlude, its citizens seized opportunities to start over, rebuild, and redefine their nation. Defeat became a creative process rather than a destructive one and the people of Japan embraced it with eagerness. In the atmosphere of reform that characterized the occupation, an efflorescence of what Dower calls “cultures of defeat” emerged. For example, kasutori culture explored the sleazy underside of urban life. Radical political movements tested the limits—and sincerity—of American reformism. Changes in artistic images, popular entertainment, songs, jokes, and even the Japanese language itself reflect the vitality and diversity of Japanese culture during the American occupation.

An aerial view of a destroyed residential area of Tokyo after the fire raids.

Dower’s Japan-centered perspective informs his judgment of the occupiers, whom he views as agents of imperialism as well as facilitators of positive change. If the occupation was a prologue to a new period of Japanese history, it was also the epilogue to an era of Western exploitation that began when Commodore Matthew Perry forced Japan to “open” to Western trade in the middle of the nineteenth century. Dower calls the occupation “the last immodest exercise in the colonial conceit known as ‘the white man’s burden.’” The occupiers, under the leadership of the notoriously vain Douglas MacArthur, lived in enclaves of lavish comfort and issued imperious edicts. Nevertheless, Dower concedes that American reforms were “impressively liberal,” and he is critical of those in Japan and Washington who resisted reform. This group includes Japanese conservative politicians as well as the “old Japan hands” in the U.S. Department of State. To Dower, these were old-fashioned elitists who sought to restrict the influence of average citizens in the new Japan. Dower’s interpretation of the American occupation as a neocolonial as well as a progressive exercise rings true, but it is a delicate balancing act.

Embracing Defeat has received high praise in the academic and popular presses, and justly so. Nevertheless, the book has certain limitations. Dower concentrates almost exclusively on the experiences of urban-dwelling Japanese. The half of the population that lived in rural areas suffered more than their share of hardship during the war, and their story of change and recovery during the occupation is as fascinating as it is neglected. Still, Dower’s exploration of urban cultures in the occupation period is a monumental task, and he executes it marvelously. Embracing Defeat‘s engrossing account of social change during the American occupation of Japan has earned it a permanent place in the literature of that epochal event.