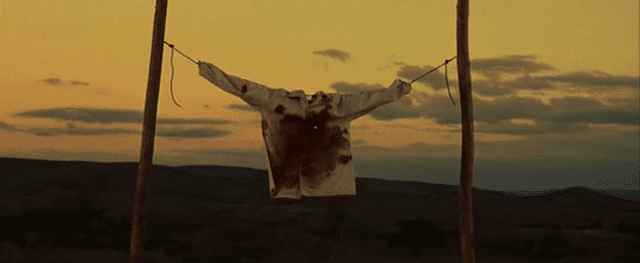

Walter Salles’ 2001 film Behind the Sun (Abril Despedaçado) chronicles the blood feud that envelops two families in the Bahian sertão (outback) in 1910. The rival Ferreira Breves clans are engaged in an unending war over land and honor. Portraits of the deceased hang on each family’s walls and their blood-drenched shirts are hung outside to signal mercy; the next killing cycle cannot commence until the blood has turned yellow. It is a depressing picture of misery, violence, and backwardness. Nevertheless, the arrival of a traveling circus and the ensuing friendships between the Breves sons and two of the performers infuse this somber story with a whimsical romanticism. Ultimately, the youngest Breves boy attempts to liberate himself and his brother from their wretched situation. The struggle, as one might expect, ends badly, but not without a note of measured optimism.

Depictions like the one in this film, with all its attendant ideas and images, are what preoccupy Durval Muniz de Albuquerque Jr. in The Invention of the Brazilian Northeast. Albuquerque, who is Professor of Brazilian History at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, is considered one of Brazil’s preeminent scholars. In this now classic study of Brazilian regionalism, the reader is presented with the story of how the Northeastern region of Brazil was “nordestinizado,” or transformed into an imagined space of misery, violence, folklore, fanaticism, and rebellion. This idea of the Northeast was “invented” by a rich archive of texts and images that achieved prominence in the 1920s and continues to influence our conception of the area and its inhabitants. Albuquerque examines a thick assortment of discourses advanced through literature, cinema, music, art, and academic production to see how they “construct and institute the realities” of the Northeast.

Depictions like the one in this film, with all its attendant ideas and images, are what preoccupy Durval Muniz de Albuquerque Jr. in The Invention of the Brazilian Northeast. Albuquerque, who is Professor of Brazilian History at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, is considered one of Brazil’s preeminent scholars. In this now classic study of Brazilian regionalism, the reader is presented with the story of how the Northeastern region of Brazil was “nordestinizado,” or transformed into an imagined space of misery, violence, folklore, fanaticism, and rebellion. This idea of the Northeast was “invented” by a rich archive of texts and images that achieved prominence in the 1920s and continues to influence our conception of the area and its inhabitants. Albuquerque examines a thick assortment of discourses advanced through literature, cinema, music, art, and academic production to see how they “construct and institute the realities” of the Northeast.

The very idea of the Northeast as a distinct region came into existence as Brazil’s central South, particularly the city and state of São Paulo, became a type of foil to the Northeast as a result of rapid and sustained industrialization, urbanization, and European immigration. Soon, travelers and journalists from the South began to disseminate accounts detailing the strange and backward customs of Northeasterners—a discourse that would continue to gain prominence with time. The onset of seasonal droughts proved a “point of unity for diverse Northern interests to raise their various complaints to the national level, at the cost of converging around a shared vocabulary of weather-based misery and suffering.” Banditry and messianic movements quickly joined the drought discourse as additional points of argument for “investing in the modernization of the North.”

In terms of culture, members of the new regional elite began to produce works that crystallized all the stereotypical perceptions of the region as fanatical, folkloric, underdeveloped and drought-stricken. The first generation of cultural elites, spearheaded by the renowned Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre, rooted their work in notions of tradition and nostalgia for the past. Albuquerque explains the preponderance of folklorizations and romanticizations in artistic and academic works as a reaction to greater nationalist strategies that heralded a radically different and “modern” idea of Brasilidade (Brazilianess) emanating from the center South. The author is highly critical of the discursive paradigm fashioned by these individuals because of its essentialization of nordestinos and their history, one that “imposed a ready-made history that naturalized the present injustice, discrimination, and misery.” A more leftist, less traditionalist group of observers painted the Northeast as a place that was naturally inclined toward revolt against exploitation and bourgeois domination from outside the region. Inadvertently, perhaps, this cemented the marginalized identity of the Northeast as a land of perpetual misery and injustice.

Underpinning Albuquerque’s analysis are the Foucaldian concepts of dispositif and gaze. Dispositif refers to the various institutional, physical, and administrative bodies and knowledge structures that are responsible for maintaining the exercise of power. Gaze, on the other hand, refers to the idea that it is not just the object of knowledge in a power relationship that is constructed, but also the knower, the person “gazing.” This underscores the extreme importance of the South, particularly Sao Paulo, in the invention of the Northeast. Throughout the study, the South acts a counterpoint to the Northeast—in fact, it is just as critical as the latter. The “modern,” eugenically superior white, Italian South essentially shapes the primitively backward African, racially-mixed Northeast. Indeed, Barbara Weinstein’s excellent new book, The Color of Modernity: Sao Paulo and the Making of Race and Nation in Brazil, illuminates exactly how the intellectuals and politicians who formulated Paulista identity during the first half of the twentieth century ardently advanced the idea that their region and its people were the vanguard of Brazilian civilization. Not only was Sao Paulo culturally and economically superior to the rest of the nation, but its citizens had a unique aptitude for social progress and modernity. Not surprisingly, this discourse of exceptionalism came neatly wrapped in explanations that emphasized the European origins of the majority of its inhabitants.

Underpinning Albuquerque’s analysis are the Foucaldian concepts of dispositif and gaze. Dispositif refers to the various institutional, physical, and administrative bodies and knowledge structures that are responsible for maintaining the exercise of power. Gaze, on the other hand, refers to the idea that it is not just the object of knowledge in a power relationship that is constructed, but also the knower, the person “gazing.” This underscores the extreme importance of the South, particularly Sao Paulo, in the invention of the Northeast. Throughout the study, the South acts a counterpoint to the Northeast—in fact, it is just as critical as the latter. The “modern,” eugenically superior white, Italian South essentially shapes the primitively backward African, racially-mixed Northeast. Indeed, Barbara Weinstein’s excellent new book, The Color of Modernity: Sao Paulo and the Making of Race and Nation in Brazil, illuminates exactly how the intellectuals and politicians who formulated Paulista identity during the first half of the twentieth century ardently advanced the idea that their region and its people were the vanguard of Brazilian civilization. Not only was Sao Paulo culturally and economically superior to the rest of the nation, but its citizens had a unique aptitude for social progress and modernity. Not surprisingly, this discourse of exceptionalism came neatly wrapped in explanations that emphasized the European origins of the majority of its inhabitants.

Although Albuquerque does not explicitly use the term “internal colonialism,” his narrative is engaged with the concept. The Northeast’s alterity thrust it into a cultural relationship with the South that is reminiscent of that between colonizer and colonized. And while internal colonialism seems like a fitting label, perhaps one should take a cue from postcolonial theorist Edward Said (as Weinstein does) and consider the concept of “internal Orientalism” as well. Orientalism is particularly enlightening because it focuses on the colonizing power and actually tells us more about the desires and identities of the “occidental architects” than it does about the “Orient.”

The Invention of the Brazilian Northeast is a fascinating exploration into an idea that endures to the present day, as films like Behind the Sun demonstrate. It is an enthralling book that will give the reader a clearer understanding of Brazilian culture.

The Invention of the Brazilian Northeast, by Durval Muniz de Albuquerque Jr., translated by Jerry Dennis Metz (Duke University Press, 2014)

You may also like:

Seth Garfield discusses his work on the Brazilian Amazon

Edward Shore reviews Quilombo dos Palmares: Brazil’s Lost Nation of Fugitive Slaves, by Glenn Cheney (2014)

Elizabeth O’Brien recommends The Deepest Wounds: A Labor and Environmental History of Sugar in Northeast Brazil, by Thomas D. Rogers (2010)

Franz D. Hensel Riveros on Hello, Hello Brazil: Popular Music in the Making of Modern Brazil, by Bryan McCann (2004)

Michael Hatch and Felipe Cruz review two books by João José Reis: Slave Rebellion in Brazil: The Muslim Uprising of 1835 in Bahia (1993) and Death is a Festival: Funeral Rites and Rebellion in Nineteenth-Century Brazil (2007)