From the editor: This month, we are joining the Institute for Historical Studies at UT Austin to discuss the Lessons and Legacies of the War in Vietnam. On November 12, 2015, the IHS is sponsoring a roundtable on the subject. It is open to the public and you can find more information here. During the month Not Even Past will continue to post articles about the war in Vietnam and we will post an episode on 15 Minute History featuring Professor Mark Lawrence, who is introducing the subject and some of his research on it, below.

On January 9, 2007, Senator Ted Kennedy stepped to the podium at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., and assessed America’s ongoing war in Iraq in words certain to grab the nation’s attention. “Iraq,” Kennedy declared, “is George Bush’s Vietnam.” The speech came amid ferocious debate in Washington and across the country about the Bush administration’s plan to resolve the war in Iraq, a grueling and bloody affair despite nearly four years of fighting, not by drawing down U.S. troops but through a “surge” in the number of American combat troops in the country. The Massachusetts Democrat insisted that George W. Bush, just like Lyndon Johnson four decades earlier, was responding to frustration by doubling down on a failed enterprise. “In Vietnam,” Kennedy said, “the White House grew increasingly obsessed with victory, and increasingly divorced from the will of the people and rational policy.” In the end, he added, more than 58,000 American died in a quest for unachievable objectives.

A marine from 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, moves an alleged Viet Cong activist to the rear during a search and clear operation (Wikipedia)

A few months later, President Bush responded in kind as he sought to convince Americans to support his escalatory policy Iraq despite the difficulties that had befallen U.S. troops up to that point. In Vietnam, just as in Iraq, Bush asserted, “people argued that the real problem was America’s presence and that if we would just withdraw, the killing would end.” In fact, said Bush, the problem in Vietnam was that weak-willed Americans prevented U.S. troops from using sufficient force and forced their withdrawal before they could achieve goals that were within reach. The result was nothing less than human catastrophe: “One unmistakable legacy of Vietnam,” Bush concluded, “is that the price of America’s withdrawal was paid by millions of innocent citizens whose agonies would add to our vocabulary new terms like ‘boat people,’ “re-education camps,’ and ‘killing fields.’”

Women and children crouch in a muddy canal as they take cover from intense Viet Cong fire at Bao Trai, about 20 miles west of Saigon, Jan. 1, 1966. Paratroopers, background, of the U.S. 173rd Airborne Brigade escorted the South Vietnamese civilians through a series of firefights during the U.S. assault on a Viet Cong stronghold. (AP Photo/Horst Faas, via Atlantic In Focus)

This debate demonstrates the intensity of the controversies that still swirl around the Vietnam War nearly 40 years after it ended. Why did U.S. leaders escalate American involvement and keep fighting despite the problems they encountered? Was the war winnable in any meaningful sense if Americans had made different decisions about how to wage it? Did U.S. leaders snatch defeat from the jaws of victory by withdrawing American troops in the early 1970s? Scholars and other writers will likely continue to debate these questions for many years to come.

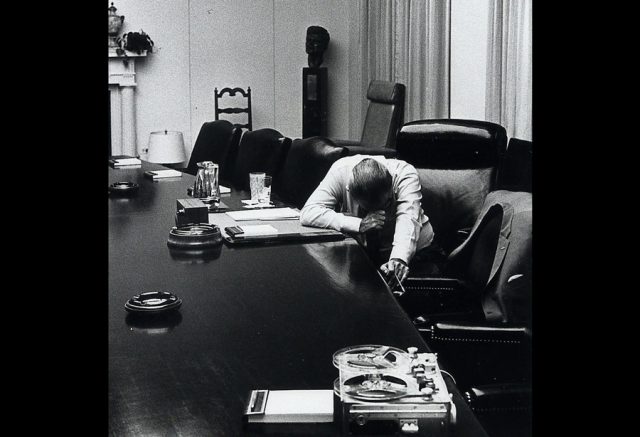

U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson listens to a tape recording from his son-in-law Captain Charles Robb at the White House on July 31, 1968. Robb was a U.S. Marine Corps company commander in Vietnam at the time. (Jack Kightlinger/AP via Atlantic In Focus)

The dueling speeches from 2007 also underscore the remarkable relevance of the Vietnam War for American politics and foreign policy in the twenty-first century. Both Kennedy and Bush understood that the war could be a powerful rhetorical device to mobilize Americans by tapping into strongly held views about the reasons for America’s defeat. They recognized as well that the war remained a widely acknowledged point of comparison in the United States for thinking about whether and how to mount military interventions abroad. For some Americans, the main lesson of the lost war is that the United States should be extremely cautious about undertaking military commitments in distant, culturally alien places. For others, the key takeaway is that the United States, once it decides to intervene overseas, must fight with maximum force and see its commitments through to the end. Policymakers will no doubt continue to invoke contrasting lessons of the war far into the future.

Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees crowd a U.S. helicopter which evacuated them from immediate combat zone of the U.S.-Vietnamese incursion into Cambodia on May 5, 1970. They were taken to a refugee reception center at the Katum Special Forces camp in South Vietnam, six miles from the Cambodian border. (Ryan/AP via Atlantic In Focus)

The Vietnam War remains, then, both contentious and important – a subject of great interest for scholars but also a matter of enduring significance in politics and policymaking. Studying the war is both a fascinating intellectual undertaking and a valuable exercise in civic responsibility. Yet exploring the history of the war is no simple task, clouded as that history is by generations of polemics and persistent uncertainty about the motives and objectives of leaders on all sides. And then there is the problem of sheer scale. According to one recent estimate, more than 30,000 books have been published about the war, a number will no doubt grow to even more staggering heights as authors gain access to new sources, especially from repositories outside the United States, and open new lines of inquiry.

My books – Assuming the Burden: Europe and the American Commitment to War in Vietnam (2005); The Vietnam War: A Concise International History; and The Vietnam War: An International History in Documents (2014) – are aimed at both shedding new light on the war and making its history accessible to twenty-first-century readers. The first book, drawing on sources from numerous archives in the United States and Europe, examines the relationship among France, Britain, and the United States between 1944 and 1950, the years when Western governments first came to see it as a Cold War crisis rather than a war of anticolonial resistance. Likeminded policymakers in each of the three key countries made common cause in order to form an international alliance aimed at defeating the revolutionary nationalists headed by Ho Chi Minh.

The second book is a sweeping narrative of the war that, unlike most standard surveys of the subject, attempts to tell the story as an episode not in American history but in global history. It delves into American decision-making and the experiences of ordinary Americans but it also examines the roles of Vietnamese of various political stripes as well as the Chinese, Soviets, and others. The third book collects about 50 primary-source documents reflecting the history of the war from the 1930s until the early twenty-first century. The book, aimed especially at undergraduate students studying the war, is designed to enable readers to draw their own conclusions about controversial matters including the nature of Vietnamese nationalism, the reasons for American anxiety about a communist takeover of South Vietnam, the nature of the South Vietnamese government, the reasons for America’s defeat in Vietnam, and the legacies of the war in the United States and around the world.

Want to read more.? Click here for Mark Lawrence’s must-read books on the war in Vietnam.