A Google image search for “Our Lady of Guadalupe” returns millions of images. This Catholic icon appears on paintings, coffee mugs, tattoos, and more. Her image is an international symbol for Catholics and non-religious alike. For Mexicans in particular, la Virgen (as she is known to them) is more than a religious symbol; she is a national symbol. In Performing Piety: Making Space Sacred with the Virgin of Guadalupe, anthropologist Elaine A. Peña explores the intersection of religious practice and national identity through the embodied practices of Marian devotees at three shrines: Tepeyac, Mexico City, Mexico; Des Plaines, Illinois; and Rogers Park, Chicago, Illinois.

The story of la Virgen begins in December 1531, when she appeared to Juan Diego, an indigenous peasant, as he walked along a hill in Mexico City called Tepeyac. This apparition story culminates in the Virgin imprinting her image onto Juan Diego’s tilma, a cloth garment. The site of her apparition became an important shrine in the newly-colonized city. Holy places like this one served an instrumental purpose for the Spanish spiritual conquest. Colonial officials reinforced the legitimacy of the shrine by incorporating it into the actual infrastructure of the city so that by 1748, the path leading to the shrine had become a major entryway into the city. The site’s importance as a holy place has grown tremendously since the colonial period. Together with the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which houses Juan Diego’s tilma, Tepeyac is today one element of a much larger holy space known as La Villa. This Marian shrine attracts millions of visitors from around the world each year.

The story of la Virgen begins in December 1531, when she appeared to Juan Diego, an indigenous peasant, as he walked along a hill in Mexico City called Tepeyac. This apparition story culminates in the Virgin imprinting her image onto Juan Diego’s tilma, a cloth garment. The site of her apparition became an important shrine in the newly-colonized city. Holy places like this one served an instrumental purpose for the Spanish spiritual conquest. Colonial officials reinforced the legitimacy of the shrine by incorporating it into the actual infrastructure of the city so that by 1748, the path leading to the shrine had become a major entryway into the city. The site’s importance as a holy place has grown tremendously since the colonial period. Together with the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which houses Juan Diego’s tilma, Tepeyac is today one element of a much larger holy space known as La Villa. This Marian shrine attracts millions of visitors from around the world each year.

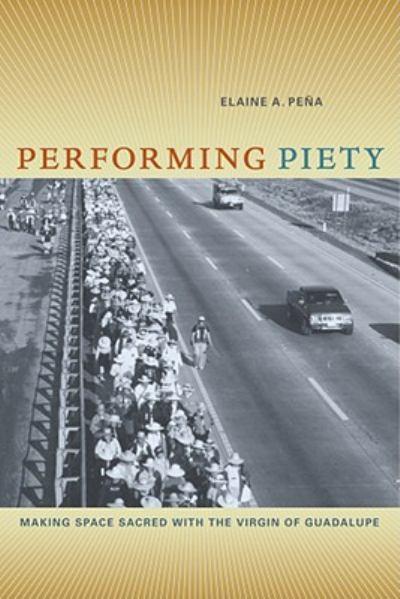

One important group of annual visitors are women pilgrims, peregrinas. There are four official, all-women’s pilgrimages to la Villa that set out from Mexican states, such as Michoacán and Morelia, usually in the days leading up to December 12, the holy feast day of la Virgen. The peregrinas walk from their hometown for days, braving heavy traffic, weather, muscle cramps, fatigue, sleep deprivation, and other hardships. Women perform this “devotional labor” for a variety of reasons. Some walk out of a sense of tradition, others are holding up their part of a bargain they made with la Virgen, and still others do so as a reprieve from family and other day-to-day obligations. Once they arrive at the Basilica at Tepeyac, the women attend an early-morning mass then take a ride on a conveyor belt that will transport them to the sixteenth-century image of the Virgin. Peña describes the moment of passing in front of Juan Diego’s tilma as a profound one for which words do not suffice. Peña joined two of these groups on their ritual of devotion to la Virgen. Her active participation, which Peña calls “co-performative witnessing,” helped her realize that while the Virgin of Guadalupe brought people together to a specific location, it was their embodied practices—prayer, song, dance, shrine maintenance—that imbued these sites with holiness.

Once they arrive at the Basilica at Tepeyac, the women attend an early-morning mass then take a ride on a conveyor belt that will transport them to the sixteenth-century image of the Virgin. Peña describes the moment of passing in front of Juan Diego’s tilma as a profound one for which words do not suffice. Peña joined two of these groups on their ritual of devotion to la Virgen. Her active participation, which Peña calls “co-performative witnessing,” helped her realize that while the Virgin of Guadalupe brought people together to a specific location, it was their embodied practices—prayer, song, dance, shrine maintenance—that imbued these sites with holiness.

Devotees of the Virgin who migrated to the United States have created new sacred spaces. In 1987, Joaquín Martínez, a Mexican national living in Des Plaines, Illinois, received a statue of the Virgin from his family in San Luis Potosí. He began soliciting the help of architects and collecting donations to build a shrine for the statue. After nearly two decades, Martínez and the Guadalupan community in Des Plaines inaugurated what came to be known as the Second Tepeyac, a replica of the Tepeyac outdoor sanctuary in Mexico City. High-ranking clergy from Mexico City’s Basilica also assisted the 2001 inauguration. Though it imitates the original, Second Tepeyac has become a multipurpose site. It is a devotional destination for the local area and community organizers hold citizenship workshops there for an increasingly diverse congregation. As Peña sees it, this site is “a sacred space and an inclusive international political haven.”

While Second Tepeyac has achieved a degree of local and transnational legitimacy, a Guadalupan shrine in Rogers Park, a neighborhood in Chicago’s far north side, has not. The area’s early settlers were European immigrants. Today, the population of Rogers Park is divided equally among white, Black, and Latino residents. Demographic changes have caused tensions, especially among longtime white residents and their new Mexican neighbors. These came to a head in 2003 over a contested Guadalupan shrine.

In July 2001, the Virgin appeared to a woman, originally from Guanajuato, while she waited at a bus stop. The woman and area residents built a shrine around the tree where the Virgin’s image appeared and they venerated her by singing traditional songs, such as “Las apariciones Guadalupanas,” which narrates the Virgin’s apparition at Tepeyac. This and other songs are also the ones that female pilgrims in Mexico sing on their pilgrimages. The neighborhood Catholic church kept its distance from the shrine and its keepers because it has strict guidelines in determining whether or not to sanction an apparition. This one did not meet those requirements.

The Rogers Park shrine also encountered resistance from other area residents, city officials, and law enforcement. Devotional practices like prayer meetings and special celebrations at and around the shrine raised the ire of neighborhoods who associated the shrine with immigrants, especially from Mexico, and saw it as an encroachment on what used to be their exclusive space. Police officials also responded negatively. When devotees sought out police protection for their holy site after vandals had destroyed it, they received an offer they could not take. Police officials claimed that the shrine attracted gang activity. They also viewed shrine devotees as potential informants. Through her own participation in meetings with the police and in conversations with community members, Peña observed how police reaction to the shrine only helped to accentuate immigrant fears and distrust of city and law enforcement officials. By November 2003, the Rogers Park shrine had been dismantled. Candles, pictures, letters and other relics that people had left for the Virgin were haphazardly stuffed into city garbage cans.

This study of performing devotion and creating sacred spaces is valuable for many reasons. It offers an insider view of modern-day women’s pilgrimages that exposes the contradictions between a centuries-old practice and modernity. Peña’s study also details the ways beliefs and practices travel, how they stay the same, and how they change. Finally, it also helps us understand the many ways that newly-arrived migrants begin building community in their new home and how they become politically empowered through community-based self-help projects.

Photo Credits:

A 16th century rendering of the Virgin of Guadalupe (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

A devotional doll of the Virgin at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

You may also like:

Janine Jones’ review of Devoted to Death: Santa Meurte, the Skeleton Saint

Kristie Flannery’s review of 2012 and the End of the World: The Western Roots of the Maya Apocalypse