While many in the US thought the world would end on November 6 when the guy they didn’t vote for won the Presidency, another whole section of the population is convinced that the apocalypse will come on December 21, 2012; the fast approaching winter solstice, in accordance with predictions made by ancient Mayans. A Reuter’s poll of 16,262 people in 20 countries conducted in May this year showed that “nearly fifteen per cent of people worldwide believe the world will end during their lifetime and ten per cent think the Mayan calendar could signify it will happen in 2012.”

These are striking figures, and ones that you might find easier to believe after scanning the results of a Google search for the terms “Maya prophecy.” Only last week the electrician visiting my apartment told me that he thinks something like the apocalypse is coming: according to 70 year old Austinite Sonny, there will be a big earthquake on the east coast of the USA, and something like 9/11, but bigger, pretty soon.

Why are so many people convinced of the world’s impending destruction? There is no doubt that pop-culture has nurtured the apparently widespread fears of the looming end of the world. Roland Emmerich’s blockbuster disaster film 2012 (released in late 2009) surely played a role in translating the Mayan apocalypse from a fringe discourse into the mainstream. Furthermore, in the past twelve months, serious news-media outlets including The Guardian have discussed the end of days as predicted by the ancient Mayans (this British newspaper published the comforting words of expert archaeologists who reassure us that “the end of the world is not quite nigh”).

What is going on here? Should we start filling the bathtub with water and hoarding stocks of canned food, flashlights, and medical supplies as December 21 approaches?

Clay rendering of a Mayan priest (Image courtesy of Wolfgang Sauber/Wikimedia Commons)

Thankfully two historians, Mathew Restall and Amara Solari, have come to the rescue with the publication of a new book 2012 and the End of the World: The Western Roots of the Maya Apocalypse. In the authors’ own words, this study “takes seriously a potentially silly topic.” Restall and Solari provide an interesting discussion of pre-conquest Maya texts, including the famous but poorly understood Long Count calendar and “Monument 6” that form the basis of the present-day “2012-ology,” a the authors call it, which anyone interested in the approaching end of the world will want to read.

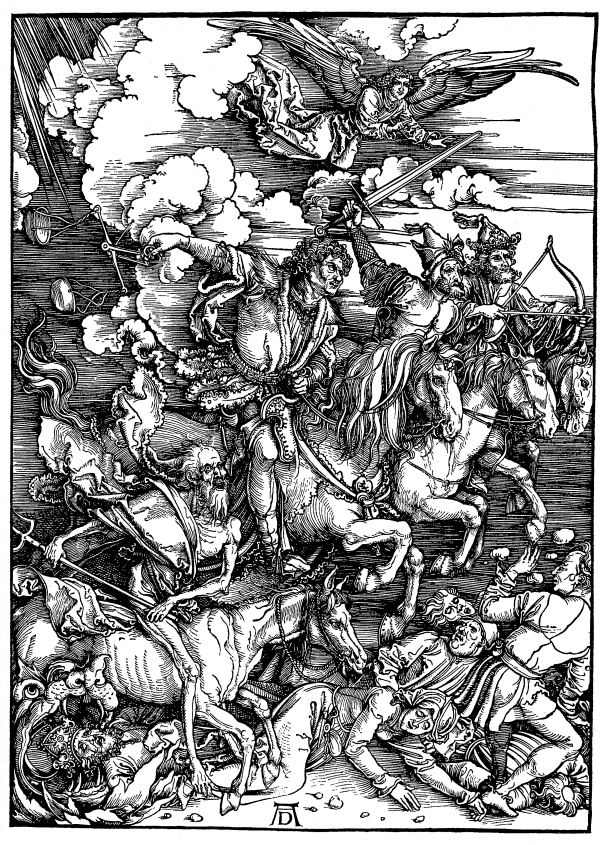

Albrecht Dürer’s 15th century woodcut, “The Revelation of St John: 4. The Four Riders of the Apocalypse” (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Restall and Solari’s most important contribution is showing that the belief in a near apocalypse is a deeply-rooted tradition in Western society. Drawing upon the Bible, the writings of the twelfth-century theologian Joachim di Diore, and Albrecht Dürer’s beautiful set of fifteen engravings of the apocalypse, Restall and Solari make a compelling argument that the origins of the Maya Apocalypse lie in the medieval European millenarian tradition. “Whereas millenarianism is not easily and clearly found in ancient Maya civilization, it is deeply rooted and ubiquitous in Western civilization. Whereas Maya notions of world-ending Apocalypse – with a capital A – was a profound and pervasive presence in the medieval West.”

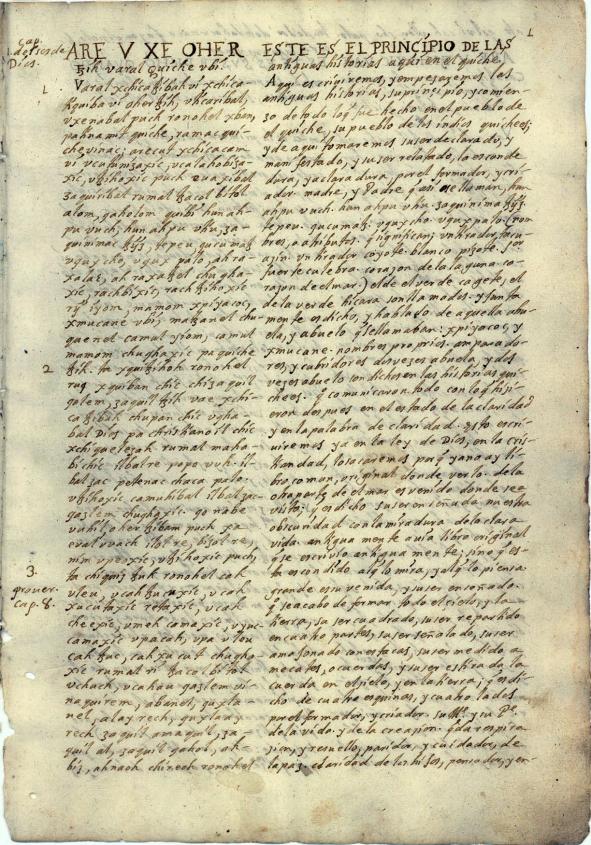

A 1701 transcription of the “Popol Vuh,” a compilation of Mayan K’iche’ creation myths (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

This book examines the survival of the apocalypse discourse from the early-modern period through to today. Restall and Solari make the bold claim that Chilism (the specifically Christian version of the belief that an impending transformation will dramatically change society), is at the heart of Western modernity – in Christianity as much as in Marxism.

A Mayan alter excavated in Caracol, Belize. (Image courtesy of Suraj/Wikimedia Commons)

Those interested in colonial New Spain will appreciate Restall and Solari’s analysis of Mayan documents such as the books of Chilam Balam (the Books of the Jaguar Prophet), which reveal how the Western apocalyptical discourse influenced Mayan conceptions of time and the world.

Watch for our December post on Milestones on the Mayan calendar and the history of the concept of Apocalypse