By Joseph Leidy

The minutes of a 1922 meeting of the Council of the Jewish Community of Salonica, today’s Thessaloniki in Greece, recorded a cordial but contentious discussion. Two guests joined the councilmen: Frank Rosenblatt and Walter Montesor, both representatives of the Joint Distribution Committee, an American Jewish charity established to provide relief for Jewish victims of the First World War. Two days earlier, the Council had submitted a report to the JDC representatives requesting five loans for different charitable projects totaling to just under a half million dollars. Rosenblatt and Montesor were to examine these proposals before forwarding their recommendations to the organization’s authorities. That thousands of Jewish families in Salonica were in great need was clear. Nonetheless, whether and how the JDC should intervene remained uncertain.

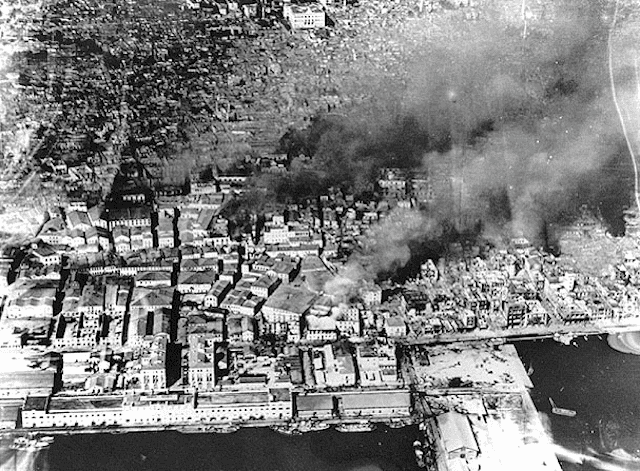

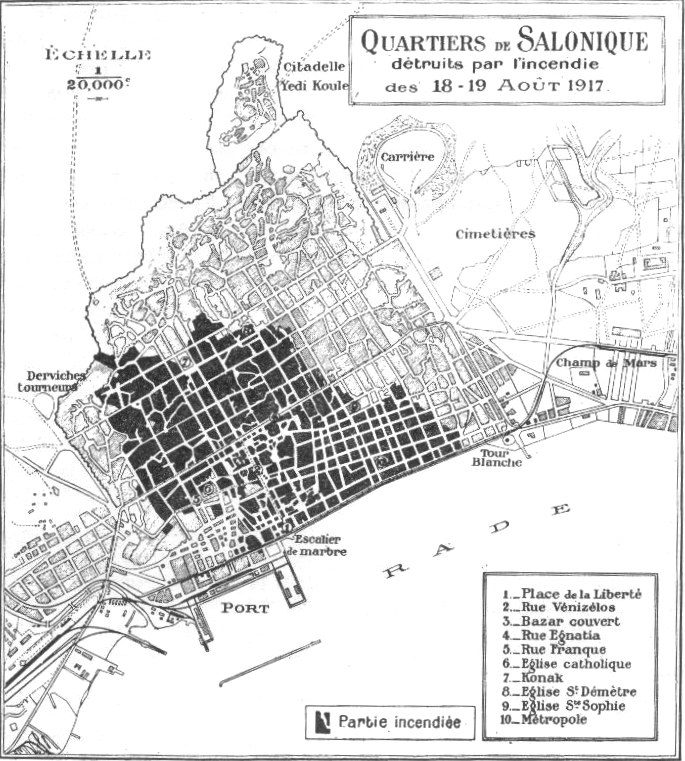

A massive fire had rampaged through the city in August of 1917, destroying the Jewish quarter and leaving tens of thousands homeless. Were these “fire-sufferers” also “war sufferers,” the target recipients of JDC relief? The Chief Rabbi of Salonica had earlier stressed to Rosenblatt that “the calamity which befell the Jewish Community in 1917 was a direct result of the war,” even though Salonica had long suffered from catastrophic fires. In the meeting, Rosenblatt emphasized that the JDC was “prepared to render aid to the war orphans in the true sense of the word, and not those orphans whose fathers died during the course of the war.” The war did not directly cause the fire, and therefore the JDC representatives seemed to have felt that direct relief should be limited.

In 1921, however, the JDC had begun to focus on reconstruction rather than direct relief, particularly devoting themselves to the tasks of increasing employment opportunities and improving sanitary conditions. Wartime restrictions on movement to and from Salonica’s port had hindered various efforts to reconstruct after the fire. Thus loan requests for reconstruction projects in Salonica, as opposed to direct relief, better fit the JDC’s mission to help Jewish communities’ general post-war recovery. Along these lines, the Council in Salonica requested funding to re-build trade schools destroyed by the fire. They also proposed the construction a new communal living quarter to relieve congestion and disease in neighborhoods of Jewish “fire-sufferers.” In both cases, the loan requests appealed to their American visitors’ social visions of enlightened charity by emphasizing economic self-reliance and proper urban hygiene. Rosenblatt and Montesor, with some minor caveats, responded positively during the meeting and indicated their willingness to recommend the loans to their superiors.

Low-lying districts, where a majority of Jews lived, were seriously affected by the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917. Via Wikipedia.

Despite these points of harmony, Rosenblatt declared that “there must have been an error in translation” with regard to one item on the evening’s agenda: a $300,000 loan for “the construction of profit yielding buildings for the Community, the revenues from which will help to increase the resources of the communal institutions.” The fire had wiped out all but a handful of previously lucrative communal properties. Rent from these properties, accumulated under Ottoman structures of communal ownership, had traditionally financed the bulk of Jewish medical, educational, cultural, and charitable organizations in the city. The Greek government’s plan to appropriate and re-design Salonica’s urban center after the fire prevented the full recovery of these assets. The community had, however, been able to purchase new plots of land at some distance from the port and city center, relatively cheap due to their proximity to malarial swamps. This loan would bankroll profitable construction on these and other plots.

Rosenblatt was skeptical. The following conversation between Rosenblatt and two council members reveals the misunderstanding at work:

Mr. Rosenblatt The principal aim of the Joint Distribution Committee is to render economic help to those communities which have suffered directly from the war […]

Mr. Cazes If the community which has suffered through the war is not helped, how will it in turn be able to help its poor people? Have not all its institutions been created to help these same people?

Mr. Benveniste In asking for this money we have the aim in view of helping our institutions who already own their profit yielding buildings, but which have disappeared on account of the war.

Mr. Rosenblatt Our desire is to help the community to rehabilitate its population, but you ask to be helped in order that you can rehabilitate the community itself in the truest sense of the world. This is quite different from our point of view.

Rosenblatt saw the JDC’s duty as being towards the individuals and families of a population. The community “in the truest sense of the world,” its legal and political governing institution, was the responsibility of its members to maintain, its wealthy ones in particular. Yet the Council’s report to Rosenblatt had already noted that “most of those who formed the rich class of Jews have emigrated, either after the fire of 1917 or on account of the economic conditions in the city.” The Council, representing the remaining Jewish elite, could not solicit enough voluntary donations during such tough times. Instead, they hoped the JDC would subsidize “profit yielding buildings” constructed on cheap land to rescue the viability of communal institutions.

These meeting minutes depict Salonica’s Jewish community at a critical juncture in its incorporation into the Greek nation-state, which annexed the city from the Ottoman Empire in 1912. The document highlights the environmental forces and understandings of nature that shaped the city’s Jewish communal life and its interactions with an American Jewish charity in the interwar period. Fire decimated much of the property that formerly sustained the organs of the community; disease then shaped the spatial arrangement of the Jewish population throughout the city by making cheap plots of land available for purchase and re-settlement of its poor. The Jewish Council sought the JDC’s help in rebuilding communal self-sufficiency on their own terms, but the JDC’s concern for sanitary conditions and their focus on combat as opposed to natural damage influenced what kinds of charitable work they would sponsor in Salonica. For Salonica’s Jews, then, the transition from Ottoman communal autonomy to Greek national citizenship was not only a question of changing identities, but also of changing relationships between local and transnational societies and the environment.

JDC Archives, Record of the New York Office of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, 1921 – 1932, Folder # 209: “Minutes of the Meeting […],” 7 Sep 1922, “Report on the Needs of the Jewish Community […],” 8 Sep 1922, “Minutes of the Meeting […],” 9 Sep 1922, “Letter from Dr. Frank F. Rosenblatt to European Executive Council of the J.D.C. Vienna, Subject: Report on Saloniki,” 26 Sep 1922.

Further Reading:

Mark Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950, Reprint edition (Vintage, 2006).

K.E. Fleming, Greece–a Jewish History (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2010).

Maria Vassilikou, “Post-Cosmopolitan Salonika – Jewish Politics in the Interwar Period,” Jahrbuch des Simon-Dubnow-Instituts 2 (2003).