By Mark Sheaves

In the summer of 2014, when the World Cup was played in Brazil, around 3.2 billion (not million!) people watched at least one game of football, or as we like to call it here in the US, soccer. That’s nearly half the world’s population. The final between Germany and Argentina played at the Maracana, the so-called “Cathedral of Football,” drew an audience of about one billion people, probably representing the largest simultaneous experience in the history of humanity. That’s nearly ten times the viewers of this year’s Superbowl. And viewing numbers are just one way of judging the global reach of a sport played in parks, streets, and beaches almost everywhere in the world. Today, it is hard to imagine meeting someone anywhere in the world who has not watched or played the global game. With the European Championships kicking off in France this June, I was wondering: What would the sport look like to someone who had never seen it played?

I found an answer while conducting research on an entirely different topic. Trawling the digitalized local newspapers from early twentieth-century Kansas, I stumbled on an article titled “A Sunday with the Scotch at Maple Hill” published in The Topeka Daily State Journal on November 16, 1912. Reading the headline I hoped that the article might be about a rowdy party involving kilts, whisky, and bagpipes. But instead it was an account by an unnamed Topeka-based journalist describing his first ever soccer game.

In the Kansas countryside, a short drive west of Topeka, two teams lined up on a patchy field of grass in late-fall sunshine. Wheat swayed in the background, cattle wondered freely, and “the fruit trees and cabbage plants and fat pasture land mocked the poor, lean newspaper men from the city.” On one side stood the Topeka team composed of descendants of “the English shires and the Scotch Glens.” Their opponents were a Maple Hill team of “eleven husky Highlanders” who worked on the farms in rural Kansas. Bigger and stronger than their urban counterparts, the Maple Hill players are described as built like bears, with jaws made of cement, and faces weather-worn by the Scotch glens and the Kansas sun. This was a game between slender, quick urbanites and a team of strong, rugged farm workers. Skill and speed took on physical power that day, which is still a recognizable dynamic in the soccer world.

And then the game kicked off and the newspapermen watched on, trying to make sense of a game with “no hidden details or smothered intricacies.” Without a sporting lexicon to draw from, the journalist relied on animal metaphors and contemporary references to describe what he saw. Some of these create wonderful images of a game played between a zoo of hybrid animals. A Maple Hill player has “a face like a hawk, hair grey as a badger and standing up like a shock. He was a bearcat to follow the ball.” At another moment, the author explains that the Topeka goalkeeper “had more troubles in the game than a bear in a bee yard.” But he reserves his best descriptions for the Maple Hill defense:

“The three Maple Hill Scots guarded the goal like a bulldog watching a baby buggy. Jackson stood like a tree. Reid had the displacement of a battleship. Warren covered the ground like a crop of wheat.”

Living now in an era where sports commentators usually draw on a set of clichés, it is refreshing to read this journalist describe the game in such original language.

At some points the game is almost entirely unrecognizable to a current soccer fan. A section titled “Kicking a ‘Human’ Goal” describes the brutal events that led to Maple Hill’s fourth goal. Moments after the Topeka goalkeeper successfully caught the ball, five of the Maple Hill “clan” bundle him to the floor and then kick the ball and man through the posts. Amazingly, the goal stood while the fans on the sidelines “swore joyously in the Gaelic tongue”. The Topeka goalkeeper “got up with the worst grouch this side of the Balkan war zone.” A picture depicts this moment, which was one of the highlights for the journalist. Such play now would probably result in a lengthy ban for the offending players, but the game played that day at Maple Hill appears to have been largely lawless.

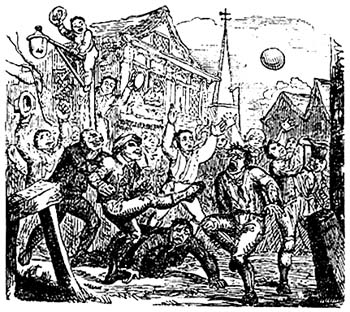

Back in 1912, the violent nature of this game should not come as a massive surprise. During the nineteenth century, Americans played a diverse range of sports involving kicking, running, and outright fighting. These games derived from ill-defined versions of rugby, football, and the medieval game of mob football, the latter being a ferocious chaotic event pitting neighboring European communities against each other as they fought to drag an inflated pigs bladder to a designated point. And of course, it was from this mosaic of sporting activities that some kind of standardized rules for American football came into being in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. While the game at Maple Hill was primarily about kicking a leather ball, and no animal innards were involved, the violence of Highlanders certainly echoes elements drawn from other sports including the recently developed American football.

This one-off game also sheds light on a largely forgotten history of soccer in the US. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, businesses, churches, schools, and ethnic community organizations established teams, leagues and associations in the hope that soccer would become the nation’s favored sport. While mid-nineteenth-century New Orleans is thought to be the first home of soccer in America, the game really took off in the northeast under the stewardship of the American Football Association, founded in 1884. By the second decade of the twentieth-century when the Maple Hill game took place, soccer matches drew large crowds in New Jersey, Massachusetts, and increasingly in cities further west such as St. Louis. The game at Maple Hill is part of this westward expansion of soccer. It was just one example of a series of matches organized by Tom Powell, a Topeka businessman, who devoted his energy to bringing the game to the Kansas area in the 1910s. However, as with most other parts of the country, these soccer initiatives declined with the increasing popularity and professionalization of American football and baseball. Yet, these early twentieth century games point to a richer history of soccer in the US than is usually recognized.

Oh, and the score between Maple Hill and Topeka? The reporter does not give it. Maple Hill certainly won, and scored at least four goals. No mention is made of a Topeka goal. This was a friendly match, in the sense that the score mattered only for pride, and for the journalist the final result mattered less than the enjoyment he derived from watching his first ever game. Perhaps this emphasis on play and community rather than results is one we might hope to return in the face of the ever-increasing monetization and business oriented approach of the sport.