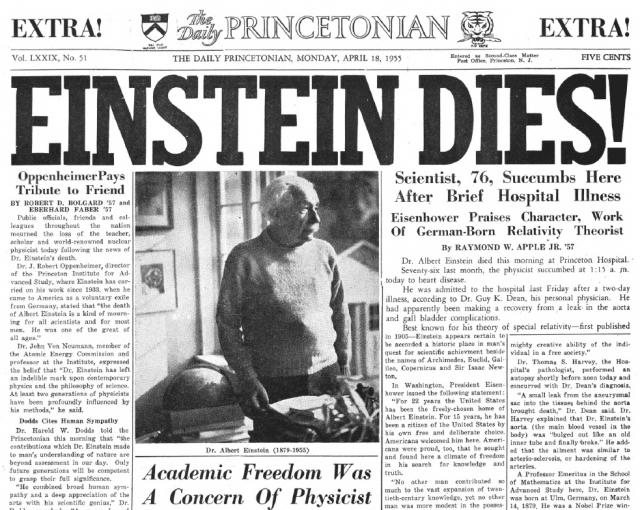

On April 17, 1955, Albert Einstein’s abdominal aortic aneurysm burst, creating internal bleeding and severe pain. He went to Princeton Hospital but refused further medical attention. He demanded, “I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially; I have done my share, it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.” In the early morning hours of April 18, the on-duty nurse heard him say a few words in German, which she could not understand, and then Einstein died.

Dr. Janos Plesch, a physician and long-time close friend who occasionally treated the physicist, thought that syphilis caused Einstein’s deadly abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). He said that Einstein was “a strongly sexual person” who enjoyed the company of numerous women even while married. Dr. Plesch conjectured that AAAs usually have a syphilitic origin. Why, he thought, would it be so unreasonable to assume that Einstein contracted syphilis on one of his escapades? Some authors have echoed Plesch’s claim, repeating it as undoubtedly true because it came from a close confidant of Einstein. But numerous studies, both before and after Einstein’s death, show that the connection between syphilis and AAAs is small. According to a study in 2012, only around 1% of untreated late vascular manifestations of syphilis result in an AAA in the descending aorta, the kind Einstein had.

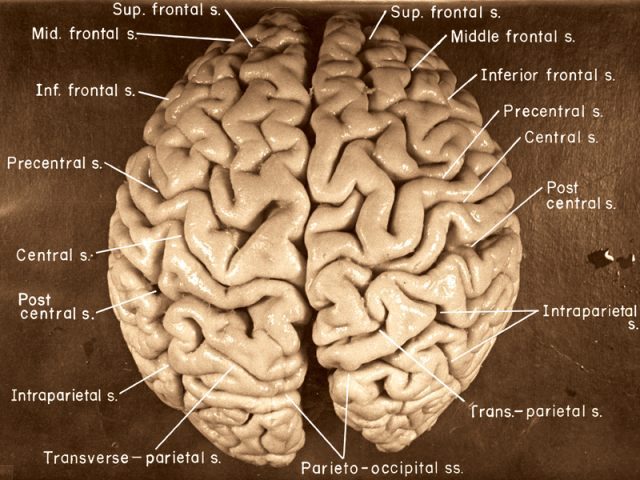

Also, no evidence of syphilis was ever reported in Einstein’s body, including his famously dissected brain. These facts do not definitively disprove that Einstein had syphilis, although it appears very unlikely, but they do beg the question: Is there a more probable explanation for why Einstein developed his deadly aneurysm? Strangely, though many scholars eagerly investigate every facet of Einstein’s life, few or none have analyzed the cause of his death.

The type of aneurysm that Einstein had is statistically linked with being old and male. However, the majority of people developing an AAA also have a history of smoking. Only lung cancer is more closely associated to smoking among tobacco-related diseases. In an analysis of risk factors for AAAs in more than three million individuals, 80% of people who developed the aneurysm were smokers. Another systematic study found that current smokers were 7.6 times more likely to have an AAA than nonsmokers. The aneurysm’s prevalence and size are strongly linked to the amount of smoking one does, and Einstein was a heavy pipe smoker for decades.

Einstein’s doctors ordered him to stop smoking during his various illnesses. He sporadically obeyed. When friends gave him gifts of tobacco during these brief periods of abstinence, Einstein would open the gift, sniff to enjoy the aroma, and then give it away to someone else. But Einstein always succumbed to the overwhelming temptation of his beloved vice. He often resorted to taking tobacco handouts from friends. Dr. Plesch especially felt sorry for the needy, embarrassed Einstein and provided him with a steady supply of tobacco and cigars despite the orders of Einstein’s other doctors and second wife, Elsa.

During his doctors’ smoking bans, when Einstein walked to the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, where he had worked since 1933, the old physicist picked up cigarette butts from the street and filled his pipe with bits of discarded tobacco. He initially walked to the Institute across from the nearby meadow, but he switched routes because the street offered more abandoned tobacco. Einstein tried to summon the courage to openly defy the bans, but he worried about offending his doctors.

In late 1948, Einstein had life-prolonging surgery to keep his AAA from bursting. The surgeon wrapped cellophane around the aneurysm. A photograph of Einstein leaving the hospital after surgery shows him inside a car with a pipe in hand. Soon after, Einstein became a lifetime member of the Montreal Pipe Smokers Club and wrote to its president, “Pipe smoking contributes to a somewhat calm and objective judgment in our human affairs.”

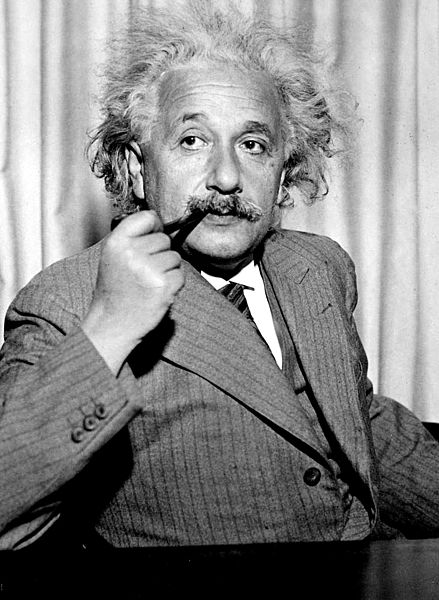

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Images of iconic figures associate smoking with intelligence: Einstein, Oppenheimer, Freud, Sherlock Holmes. The pipe gives them a pensive aura. Einstein depended on smoking—not for his genius, as some writers claim, but as a repetitive set of actions to soothe and comfort. For Einstein, this was a tolerable trade-off for his health and, ultimately, his life.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.