Borrowing its title from Led Zeppelin’s first album, Richard Linklater’s classic film Dazed and Confused continues to resonate with filmgoers and critics decades after its release. This September marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of Linklater’s cult hit and the overwhelming surge of Dazed and Confused viewing parties along with its re-release in theaters reveals the staying power of this small budget high school comedy. Linklater’s film is difficult to describe to those who have never seen it. In fact, the plot can seem quite uneventful. It lacks the drama, heartbreak, and seemingly high stakes of conventional high school stories and instead takes its viewers on a journey into the everyday banalities that make our lives what they are. Linklater’s film shows us how many of our life defining moments occur in the daily minutiae we experience.

The film takes place within a twenty-four-hour period on the last day of high school in Austin, Texas. Freshmen are hazed, the teens party under one of Austin’s legendary moontowers, and the story ends with a trek to purchase some killer Aerosmith tickets. The film perfectly encapsulates both the silly and startling aspects of high school. Whether you’re the anxious senior grappling with questions of the post-graduation unknown or the vulnerable freshman dazed by a new high school student hierarchy that feeds off freshman fear, the film captures the ethos of the high school experience. However, it would be easy to simply brush the film off as a lighthearted comedy that oozes nostalgia and brings its viewers back to the glory days of kegs, cruising, and classic rock. Linklater’s film exposes a new type of youth culture and lifestyle movement, referred to as slacker culture, born out of the failures and successes of radical domestic political and cultural movements collectively referred to as the American counterculture.

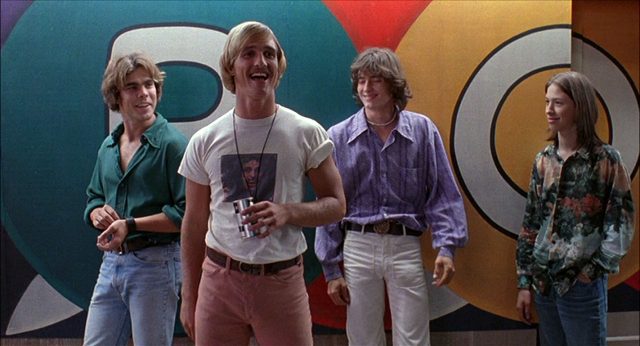

From left to right: Don (Sasha Jenson), Wooderson (Matthew McConaughey), Pink (Jason London), and Mitch (Wiley Wiggins) outside the bowling alley (via IMBd)

This new slacker culture emerged in the 1970s and consisted of a new type of cultural persona that fused the hippie with the dispirited misfit. The slacker embraced aspects of hippie culture that reinforced the right to be whatever type of individual you felt like being, but abandoned hippie political projects and radical ideologies. Slackers embodied an optimistic aimlessness while their politics celebrated choice and championed individual liberty. Slacker politics valued personal autonomy but rejected ideology and overarching political programs. Slackers were the non-participating participants. People with a point of view who lacked a cause.

The most vivid example of this slacker politics is represented in the storyline of the film’s most prominent character, Randall “Pink” Floyd. At the beginning of the film, Pink’s coach asks him to sign a sobriety pledge. The coach is concerned with winning a championship and does not want any of his players jeopardizing their chances of a winning season. Pink’s ambivalence toward the request lasts throughout the film as he grapples with options that include refusing to sign the pledge, quitting the football team altogether, or submitting to his coach’s authority. He ultimately refuses to sign the coach’s pledge but states that he will continue to play football regardless. Pink cites his right to privacy and above all else his independence when he refuses to sign the pledge. His refusal is more than teenage disobedience or protest for the sake of protest, yet the refusal is not an attempt to change the coach’s views on drug and alcohol use or pressure the coach into dropping the pledge requirement in its entirety. His protest is a statement about individual autonomy and the right to choose how to engage with the world on your own terms. The pledge is not portrayed as a collective issue that can be challenged by the gripes of the student body, but one that each football player must come to terms with on their own. If Linklater’s film was set in the sixties one cannot help but imagine the hippie version of Pink’s character staging an all-night sit-in or demonstration to protest the pledge with his fellow classmates.

Michelle (Milla Jovovich) in Dazed and Confused (via IMDb)

Pink’s decision at the end of the film embodies a slacker culture equipped with its own set of new cultural attitudes and political understandings. Slackers were indebted to a countercultural revolution that altered societal norms and changed the way America’s youth engaged with sex, drugs, and of course rock ‘n’ roll. However, these seventies slackers were left to face the fallout of a post-hippie and post-countercultural society where a new generation of young Americans lacked a cause or revolutionary project. By the late 1970s, the radical political movements that emboldened America’s youth for over a decade faded away and a new personal politics that emphasized individual choice and personal growth emerged. The high school slackers portrayed in Dazed and Confused embody this new personal politics and illustrate the evolution of youth culture following the death of the counterculture.

Linklater’s teenage characters can easily seem apolitical, inward thinking, or even lazy. One could view the characters’ priorities of getting high and hanging out as humorously pathetic, or a symptom of a group of teens with little professional and academic drive and nothing better to do. However, it would be a mistake to think that the film simply portrays a group of idle and self-centered teens looking for a good time. The film is punctuated with moments of self-reflection when its characters expose the depths of a new political attitude. Throughout the film, characters contemplate inherently political questions such as how to live a happy life, how to be true to yourself, and what it means to be free.

Director Richard Linklater (via Flickr)

While cruising the boulevard on the way to the moontower party, nerdy student Mike Newhouse reveals to his friends that he has decided not to go to law school. His dream to become an ACLU lawyer and “help the people that are getting fucked up and all that” has vanished. It only took a disastrous trip to the local post office where he witnessed a room full of pathetic people drooling in line to realize he is a misanthrope. When his friend asks him what he plans to do instead of going to law school he simply replies that he wants to dance. Linklater’s film is littered with these short but insightful moments that expose the ins and outs of slacker culture. Mike’s statements are laughable, yet they represent a decision to reject conventionalities and embrace an honest life. Mike believes it would be a lie to become a lawyer, even though he would be helping people in need. Linklater’s collection of stoners, slackers, and dreamers believe in staying true to themselves and being honest about who they are even if that means withdrawing from the world. Slacker politics is based in the banalities of everyday life and encourages individuals to follow the whims of their own hearts.

As the twenty-fifth anniversary of Dazed and Confused approaches, it is worth recognizing the indisputable contribution Richard Linklater has made through his reflective storytelling. In Dazed and Confused, Linklater offers us more than a stoner cult classic or sentimental high school comedy. The film not only captures the zeitgeist of the slacker movement but also provides insight into a cultural moment in American history. Dazed and Confused showcases a young generation’s struggles, dissatisfactions, pleasures, and truths. It navigates the rocky terrain of adolescence as young misfits, dreamers, and stoners discover who they are and how they want to live their lives.

Also by Ashley Garcia:

You may also like:

Demystifying “Cool:” A Brief History by Kate Grover

Popular Culture in the Classroom by Nakia Parker