On September 23, 1873, Japan’s young emperor Meiji received tragic news. His consort, Hamuro Mitsuko, had died, five days after delivering a stillborn boy. Sadly, such deaths were not uncommon. The imperial house suffered from high rates of maternal and infant mortality, probably due to some combination of inbreeding and poor diet. Ironically, their elite diet of white rice, unlike the humble Japanese diet of brown rice and millet, led to vitamin B deficiencies and related health problems. One detail of Mitsuko’s labor and delivery warrants special attention, even almost 150 years later. Mitsuko was attended by Kusumoto Ine (1827-1903), Japan’s first female physician.

Kusumoto was an unlikely candidate to serve the imperial house. She was the daughter of a Nagasaki courtesan named Taki, rather than an elite family. Her father was not Japanese, but rather a German physician, Franz von Siebold, who had worked for the Dutch East India Company. Siebold was banished from Japan when Ine was only two. He had exchanged maps with Japanese scholars and physicians, and the shogunate concluded that he was a foreign spy.

By almost every measure, she was an outsider: the mixed-race, illegitimate daughter of a courtesan and a foreigner. Ine’s rise from humble origins to the highest circles of Japanese society was part of the revolutionary potential of Japan in the 1860s and 1870s. For bold and ambitious people like Ine, the window between the collapse of the old order, the Tokugawa shogunate, and the consolidation of the new Meiji state, was a period of possibility. For a relatively brief historical moment, Ine’s intelligence and skill mattered more than her birth status or gender. Ine was “born at the right time.”

In an earlier generation, Ine’s career would have been thwarted by conventional Japanese restrictions on women in the public sphere, as well as the traditional status system. While many Japanese women acquired basic literacy, and some became accomplished poets, women rarely learned classical Chinese, which was central to higher learning. Nor would Ine have been able to transcend her low status. Access to the emperor was so restricted that when the Emperor Nakamikado wished to view an elephant in 1729, the animal first had to be given imperial court rank. And in the early 1800s, the imperial court would not have been interested in a doctor trained in Western medicine.

In a later generation, Ine would have faced different challenges. Beginning in 1868, the new Meiji government instituted “westernizing” and “modernizing” reforms, including new western-style universities. That interest in western knowledge helped advance Ine’s career, since she had learned western-style medicine from her father’s circle of students. But the Meiji government’s westernizing reforms included western-style restrictions on women. Following western models, Japan began to regulate medicine, requiring licensing exams and formal training at recognized schools. But those schools, also following western models, were almost exclusively male. Ine rose to prominence before those restrictions, and she was allowed to continue practicing medicine under a “grandfather clause,” but only as an “old-style midwife” rather than a physician. Thus, the new Meiji government did not liberate women so much as change how it would deny them positions in public life. Viewed from the perspective of Ine’s life, the samurai who “modernized” Japan merely introduced Victorian patriarchal norms to replace Neo-Confucian restrictions.

Much of Ine’s life seems remarkably “modern.” She was an accomplished professional woman who moved in the highest circles of Japanese society. In the 1860s, before serving the imperial house, Ine worked as house physician to the lord of Uwajima. Seeing her treated with respect by the nobility, foreign observers assumed she was of samurai status.

Ine’s family was global and sprawling. She reconnected with her father in the 1860s, after he was allowed to return to Japan, and established a relationship with her half-brothers Alexander and Heinrich, Siebold’s sons by his German wife. Ine chose to raise her daughter, Tada, as a single mother. Tada’s father was Ishii Sōken (1796–1861), one of Siebold’s students and Ine’s teachers. Ine accepted Sōken’s instruction and professional support, but refused to marry him. Her decision likely had a #metoo component: after her mother’s death, Tada reported that Sōken had raped Ine. Ine navigated that fraught relationship with determination, rejecting Sōken’s marriage proposals but accepting his career help.

But Ine’s story also shows the “lumpiness” of history — there is rarely a straight path from “then” to “now.” Rather we find moments in the past that seem more “modern” than recent events. Ine’s story leaps out to us as an example of events from 150 years ago that seem immediate and directly connected to our present moment.

For more on the “lumpy” history of modern Japan, see:

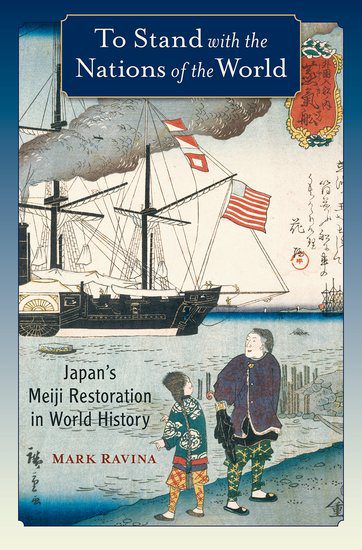

Mark Ravina, Stand with the Nations of the World: Japan’s Meiji Restoration in World History (2017)

Marius B. Jansen, Sakamoto Ryōma and the Meiji Restoration (1961). A classic study of a charismatic rebel leader of the 1860s.

Anne Walthall, The Weak Body of a Useless Woman: Matsuo Task and the Meiji Restoration (1998). A thoughtful feminist intervention: the Meiji Restoration as seen through the life of a politically engaged woman poet.

Mark Ravina. The Last Samurai: the Life and Battle of Saigō Takamori (2004). My biography of the most controversial figure in the early Meiji government

Top image credit: Kawahara Keiga, Arrival of a Dutch Ship, depicting Ine, Taki, and Siebold at Dejima (Wikipedia).