The late Professor Norman D. Brown was a fixture of the UT Austin History Department for nearly four decades, and his classes on Texas history were popular favorites among undergraduates and graduate students. In 1984, Texas A&M University Press published Brown’s Hood, Bonnet, and Little Brown Jug: Texas Politics, 1921-1928, which is still considered the main source for the state-level political history of that era. In the ensuing decades, Brown worked steadily on a sequel, which he never published before his retirement from UT Austin in 2015.

That sequel, Biscuits, the Dole, and Nodding Donkeys: Texas Politics, 1929-1932, unveils little known stories of the high drama of the Texas political scene at the beginning of the Great Depression. Yet these stories might never have seen the light of day if it weren’t for the efforts of some of Brown’s devoted former students and colleagues.

Norman D. Brown with Rachel Ozanne, ed., Biscuits, The Dole, and Nodding Donkeys: Texas Politics, 1929-1932

Brown donated his personal papers and research files to the Briscoe Center for American History when he retired. Unknown to many, this donation included his unfinished book manuscript. A former Master’s student of Brown, Josiah Daniel, learned of the manuscript’s existence, and, with the support of the Briscoe Center, contracted with the UT History Department to find an editor for the manuscript. In 2017, I was hired to update the scholarly references in the manuscript’s footnotes and to write an introduction for the manuscript, summing up its main ideas and themes. I was quickly delighted with the rich details of the highs and lows of Texas gubernatorial, legislative, and party politics that Brown portrayed. The manuscript came to me without a title, but I settled on Biscuits, the Dole, and Nodding Donkeys as key images that encapsulated the major ideas and issues of this critical era in Texas history.

“Biscuits” refers to the on-going role that personality and populism played in Texas politics. Throughout most of the twentieth century, the Democratic Party dominated the state of Texas. The Republican Party was too closely associated with Abraham Lincoln and the defeat in the Civil War to appeal to most white Texans, and most black Texans were prevented from voting due to Jim Crow laws that in effect disfranchised them. In the 1920s and 30s the Texas Democratic Party was divided between two factions that fought for control of the party: business progressives, who sought to reform certain aspects of government to provide improved social services, and populists, who sought to prevent the expansion of the size and scope of government and claimed to appeal to the people, mostly poor, rural white Texans.

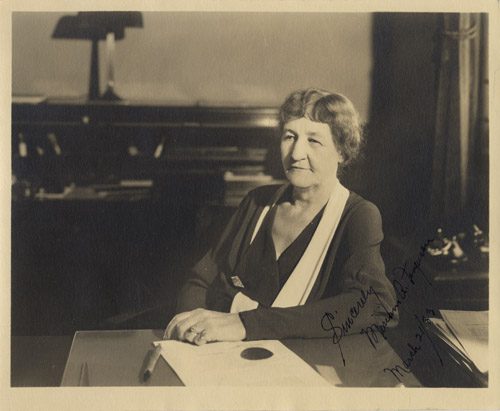

Ma Ferguson, 1933 (Paralta Studios, Austin. Briscoe Center for American History)

In Brown’s narrative, Jim “Pa” and Miriam “Ma” Ferguson best represented the populist wing of the Democratic Party. Pa Ferguson was governor in the 1910s, but was barred from holding public office after being convicted of misappropriation of public funds and other charges in his 1917 impeachment trial. Ma Ferguson ran for reelection to the governorship in 1932, promising “two governors for the price of one.” In explaining his political philosophy, Pa asserted that you’ve got to keep the people happy, or “give them a biscuit.” As long as you kept giving them people biscuits, they would be “for you,” but as soon as the biscuits ran out, “they [would] not be for you any longer.” The Fergusons’ populist appeal was successful in 1932, but they soon found themselves falling from public favor, as new rumors of abuses of public funds and power surfaced again.

Texans also argued among themselves about “the dole” and the extent to which they were comfortable with government intervention. The Great Depression presented Texans with a social crisis of poverty and unemployment the likes of which they had never seen, making them more receptive to the possibility of federal and state programs than ever before. Brown notes that every successful gubernatorial candidate in Texas in the 1930s ran for office promising to provide a pension program for elderly Texans, but efforts to implement these plans were always prevented by the state legislature.

East Texas Oil Fields, Derricks and Buildings (Briscoe Center for American History)

Texans also flirted with stricter regulations on production for the oil industry—the “nodding donkeys” of the era—particularly regulations that would limit the number of barrels produced per day. Brown documents what happened when a massive oil field was discovered in east Texas near Kilgore in late 1930. Wildcat, individual producers rushed to the area to drill wells to capture as much oil as possible, hoping to make a quick profit, before large producers came in to dominate the area. Their efforts led to massive decreases in prices and to environmental waste, as much of the oil evaporated or flooded nearby fields, when it could not be contained. These smalltime producers opposed efforts by Governor Ross Sterling to regulate production, arguing that limiting production in order to stabilize and increase prices violated the law (it did). Governor Sterling eventually declared martial law in east Texas to try to enforce production quotas, but one-by-one oil companies filed court injunctions that made the attempt to enforce production quotas impossible. In the long-term the legislature did pass new laws allowing for better restriction of the oil industry, but too late to affect the situation in Kilgore.

Vice President John N. Garner –“Cactus Jack– and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, c. 1930-35 (Briscoe Center for American History)

Brown’s book concludes with a dramatic recounting of the Democratic Party’s Primary Convention in Chicago in 1932, as Texans considered whether to throw their support behind native son John Nance “Cactus Jack” Garner or New Yorker Franklin D. Roosevelt—revealing the critical role that Texans ultimately played in securing the nomination for Roosevelt.

These stories and others make Brown’s work highly recommended for lovers of Texas history or political history in general.

Norman D. Brown with Rachel Ozanne, ed., Biscuits, The Dole, and Nodding Donkeys: Texas Politics, 1929-1932

Want to know more? You can listen to Rachel Ozanne talk about Brown’s book on the Texas Standard’s website.

George Norris Green’s The Establishment in Texas Politics: the Primitive Years, 1938-1957 picks up the story of Texas political history about where Brown’s Biscuits leaves off.

Walter L. Buenger’s The Path to a Modern South emphasizes the economic developments of Texas history as well as Texans’ shifting understandings of their state identity in the years leading up to and through the era of Brown’s work.

Darlene Hine Clark’s Black Victory: The Rise and Fall of the White Primary in Texas highlights the political history of African Americans in Texas in the first part of the twentieth century.

Neil Foley’s The White Scourge provides important insight into the racial history of Texas during the era of Jim Crow, by examining not just the issue of white and black racial conflict, but the complexities of racial tension in a state with a substantial Mexican American population in the early twentieth century as well.