This article was originally posted in the Briscoe Center for American History’s Newsletter.

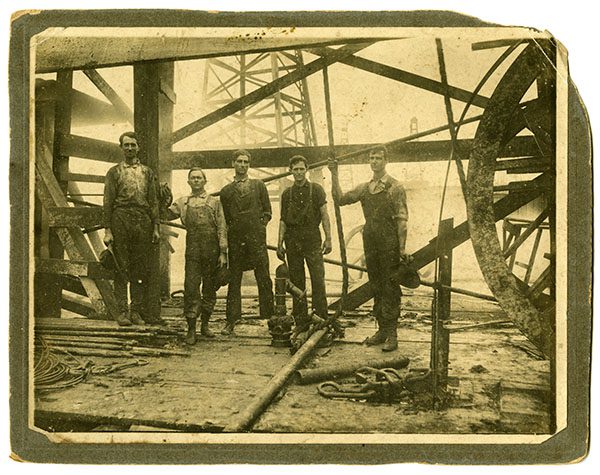

In 1918, Spanish influenza ravaged a war-weary world, killing as many as 40 million people across the globe and over half a million in America. In the oil fields of Texas, the flu was particularly vindictive due to poor working conditions and a lack of health care. The Oral History of the Texas Oil Industry Records include interviews with roughnecks, rig managers, mule skinners, and Red Cross workers who witnessed the flu firsthand. Below are four excerpts from the collection.

Walter Cline, Red Cross worker in Burkburnett, Texas

“And we had what you and I now know to be the worst flu epidemic we’ve ever had in the United States. I was serving as field director for the Red Cross at the time in charge of Red Cross field operations at Call Field near Wichita Falls. . . . We got the government to assign some doctors and nurses to try and relieve the situation. . . . We asked the people of Wichita Falls to contribute in order that we might find shelter and food and warm clothing and medicine for the people, many of whom were suffering from flu and exposed in covered wagons and under these tarpaulins. . . . In one place, you’d find a mother dead, with a little six or eight months old baby crawling around over her breast, trying to open her dress. And you gather her up and look around and her husband is sick over there and a little boy. I think on our first trip west of Burkburnett, we gathered up some six or eight dead men, women, and children, and they continued to die until we found temporary shelter for them.

The people in Wichita Falls were most generous and helpful. They shipped lumber and bedding and food and clothing by carloads. As I recall it, the railroad hauled it to Burkburnett free of any freight charge, and the teamsters, the oil field haulers, hauled it out to where it was needed without any charge. And it was possibly one of the saddest sights I’ve ever had to experience . . . it was rather saddening to see thousands of people, and there were thousands of them, suffering and dying and little we could do about it. We finally stopped it . . . we had a reputation for taking care of the folks that couldn’t take care of themselves. They parked along the riverfronts and pitched camp and we tried to feed and shelter them and give them medicine and take care of them through the winter. And it was rather a severe winter.”

Burkburnett lies close to Wichita Falls in northeast Texas. In 1912 oil was discovered west of Burkburnett, but a much larger find was made in 1918, drawing approximately 20,000 people to the area. “Of course, there was a tremendous influx of people,” recalled Cline. “Crop conditions had been very poor over most of southern Oklahoma and western Texas, and there were thousands of families who were suffering for enough food and clothing and shelter to carry them through the winter months.” Many of these families found work in Burkburnett. But they also found the flu. By the end of 1918, the oil field was producing 7,500 barrels per day, and twenty trains ran daily between Burkburnett and Wichita Falls. These figures suggest managers prioritized profit over public health. Due to the transient nature of the working population, it is not clear how many people died. The oil boom died out by 1930.

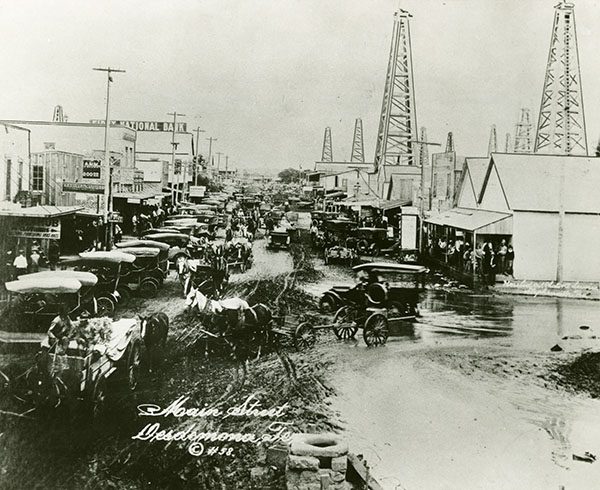

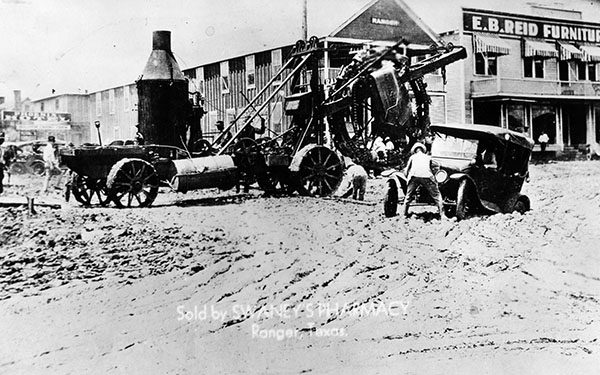

G. Lawson, oil rig worker in Ranger, Texas.

“I was in Ranger when they had this flu epidemic, and that was about the most pitiful thing that I have ever seen. I have seen parents carrying children down the street on their shoulders unable to raise their heads, taking them to the doctor’s office. Seen caskets just piled up—bodies in them I suppose—ready to be shipped out. That was one of the hardest things to see.”

Born in West Virginia, Lawson worked in oil fields across the United States and Mexico wherever he could find work. In 1917, he came to Ranger, Texas. Ranger, between Fort Worth and Abilene, was an agricultural town. Hard hit by drought, locals initiated a successful search for oil. By mid-1917, McClesky No. 1 reached a daily production of 1,700 barrels. The discovery kicked off an oil boom that radically transformed both Ranger and the surrounding Eastland County. Unsanitary conditions caused by makeshift housing and torrential rain led to outbreaks of typhoid. In 1918, when Spanish flu began to spread, the town was ill-prepared. However, work in the oil fields never abated, no doubt one of the reasons the flu hit so hard. By 1919 there were 22 oil wells in the area. By 1921, most of the wells were spent.

Fred Jennings, rig manager in Goose Creek, Texas

“The people died [in Goose Creek, Texas, east of Houston] and they just died so fast here till they didn’t have no undertakers. You’d just have to put them in pickup trucks and haul them to Houston. Just put them in a pine box and bury them any way you could. That went on—well, that was 1918. That was through the winter months of 1918, when the flu epidemic was so bad . . . and men—I saw one man working and walk home and was dead in thirty minutes after he came home with that flu.”

Born Gonzales County, Fred Jennings settled in Goose Creek in 1916, eventually working his way up from roughneck to rig superintendent. In 1917 Ross S. Sterling, president of Humble Oil and future governor of Texas, pioneered a railroad connection to the Southern Pacific line at Dayton, leading to a boom—“30,000 people into the area overnight,” according to Jennings. In his interview, Jennings discusses the conditions in the town before and after the flu epidemic. Topics covered include strike action, the declaration of martial law, fist fights, gunfights, the poor treatment of women, and the arrival of the Ku Klux Klan.

Plummer Barfield, mule train operator in Jefferson County, Texas

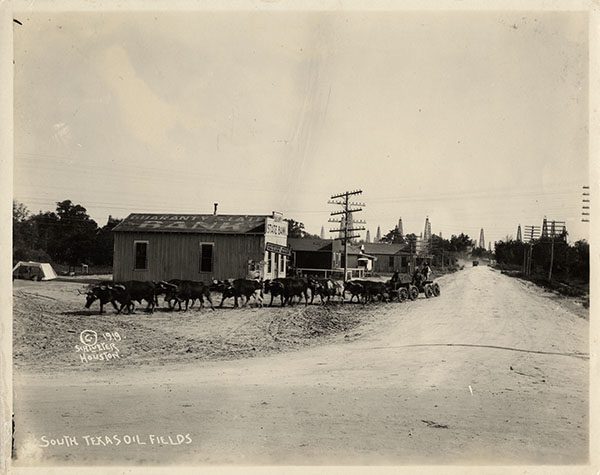

“Even as late as ’19 and ’20, well, we were pretty short-handed during the flu epidemic around the cemetery because—especially in the fall and the early spring of ’19 and the early spring of ’20, when the epidemic was at its worst, why, people was just afraid to get out. And I’ve had— conducted several funerals that there wouldn’t be nobody there but maybe a brother, or maybe a son or the father of one, or a gravedigger and myself in any number of cases. And the preachers, at one time here, all of our local preachers were sick, and everybody worked to death in this neck of the woods, and you just couldn’t get nobody. Lots of times we wouldn’t have enough for pallbearers. . . . But those things couldn’t be helped and they understood, . . . people that had been sick didn’t have any business out. . . . And most of them was afraid they were gonna be sick and they wouldn’t get out unless they had to. So it was pretty severe in this neck of the woods for about six months.”

Plummer Barfield grew up in Jefferson County. He worked in livery stables for much of his life and ran mule trains that carried supplies to a variety of oil fields between Beaumont and Houston during the 1910s and 1920s.

About the Oral History of the Texas Oil Industry Records

Created in the 1950s, the Oil Industry Records project was commissioned by Estelle Sharp. Her husband, Walter Sharp, was one of the early Spindletop drillers. Mrs. Sharp saw the need to gather the recollections of those who worked during the early Texas oil boom. The collection includes 218 taped interviews that have since been transcribed. The Briscoe Center is in the process of digitizing the entire collection and making it available online.

You might also like:

Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Confederacy”

Documenting Slavery in East Texas: Transcripts from Monte Verdi

Remembering the Tex-Son Strike: Legacies of Latina-led Labor Activism in San Antonio, Texas

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.