Aaron T. Pratt is the Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Curator of Early Books and Manuscripts at the Harry Ransom Center. This is the first in what we hope will become a regular feature introducing some lesser known objects and texts in the Ransom Center’s remarkable collections.

Long before computer mice and touchscreens made it possible to manipulate complex digital interfaces with ease, volvelles were cutting-edge information technology, transforming the otherwise static surface of the page into an interactive vehicle for learning and knowledge creation.

From Latin volvere, a verb meaning “to turn,” “volvelle” emerged in the Middle Ages as a noun that emphasizes the dynamic nature of new rotating or “turnable” devices that were being made of parchment and paper. First designed for inclusion within medieval manuscripts, volvelles and other interactive diagrams proliferated with the advent of print. They demonstrate both the ingenuity of medieval and early modern thinkers and the technical skill of the printers and bookbinders who helped bring their ideas to broader audiences.

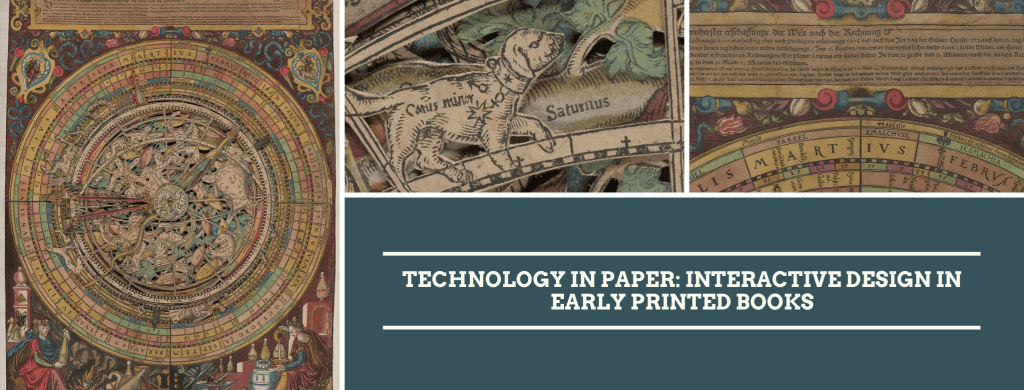

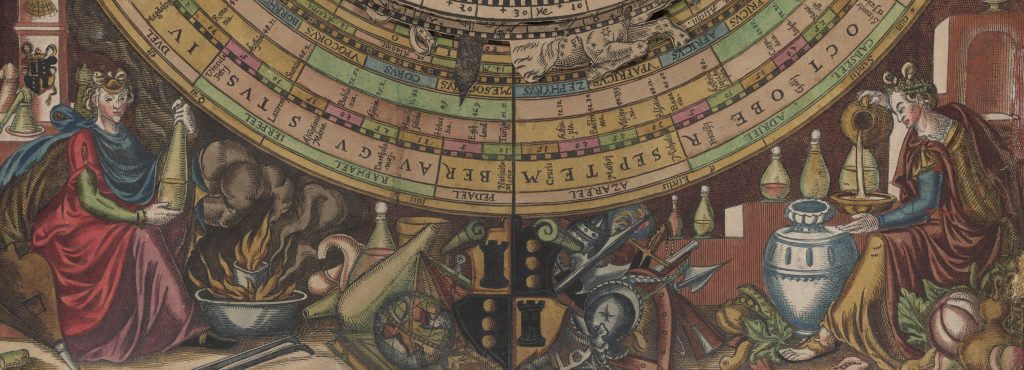

The large volvelles created by Leonhard Thurneisser zum Thurn (ca. 1530–ca. 1596) are among the most elaborate ever printed.

Thurneisser was a German polymath who earned a reputation as a miracle doctor. In 1571, he became the personal physician of Elector Johann Georg of Bradenburg after helping his wife through an illness. Johann Georg subsequently furnished him with space in Grey Abbey, a former monastery in Berlin. There, Thurneisser established his home, along with a library, laboratory, and printing operation.

Thurneisser designed and printed eight paper machines around 1575. Meant to accompany the second edition of his alchemical and astrological treatise, Archidoxa, they are tools to help readers determine the influence that the heavens would exert on their lives and the natural world. In essence, they are horoscope calculators.

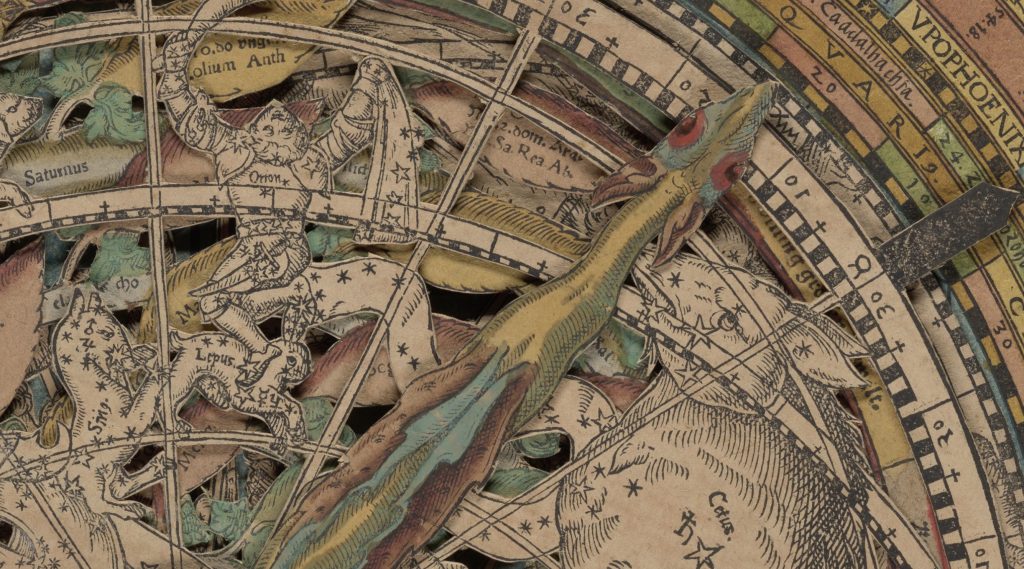

In each, a woodcut frame surrounds the base of each device. At its foot, the frame depicts female alchemists with the tools and symbols of their craft, connecting alchemy to astrology as an associated art. The volvelles themselves are made from as many as seven distinct parts, and, with their curves and fine lines, they would have been a challenge to cut out and assemble.

The serpentine dragons that serve as pointers are particularly striking, but look closely and you can find detailed constellation charts among the lower layers.

Thurneisser’s volvelles remain an ambitious—and visually stunning—instance of early interface design. Some sets remain black and white, but the Ransom Center’s set has been colored by hand.

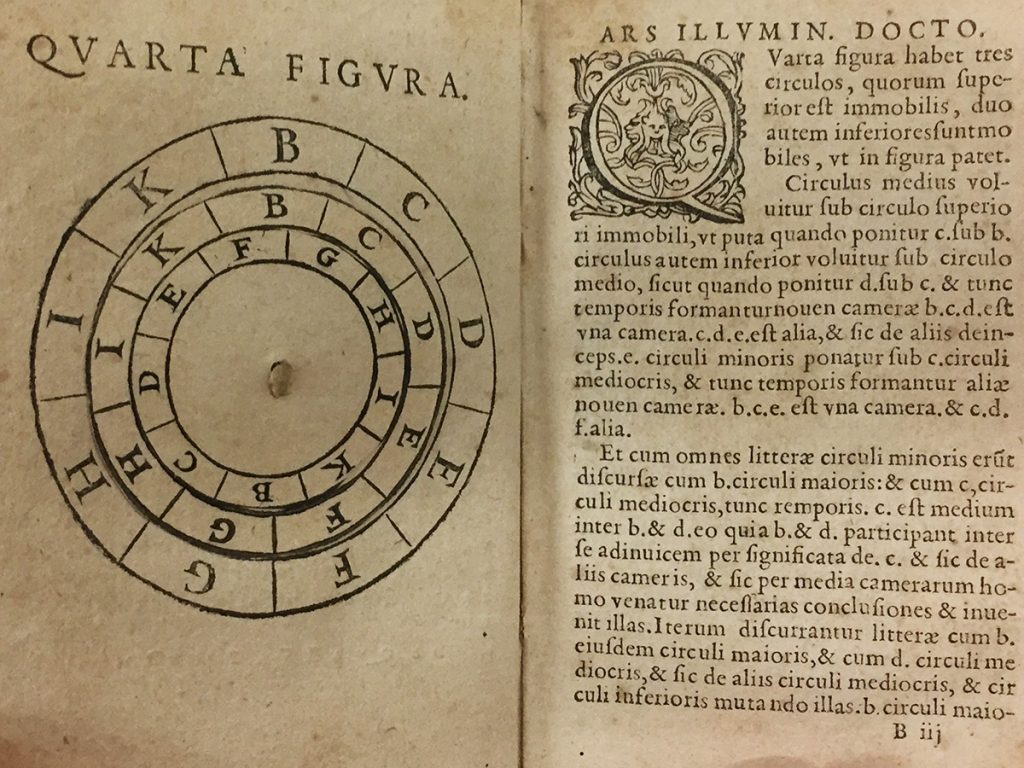

There are other examples of volvelles in the Ransom Center. Active during the later thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, Ramon Llull (ca. 1232–ca. 1316) dedicated much of his prolific career as a writer to the goal of converting Muslims to Christianity, and in the process became one of the earliest—and most influential—volvelle-makers. A 1578 edition at the Center includes an instance of the volvelle he integrated into his Ars brevis. It combines the letters of a symbolic alphabet, which is designed to help readers contemplate important questions and arrive at Christian truths. For example, Llull writes that the combination “BCD” can help readers contemplate “whether any goodness is as infinitely great as eternity.” (Llull’s answer is “yes; otherwise all the greatness of eternity would not be good.”)

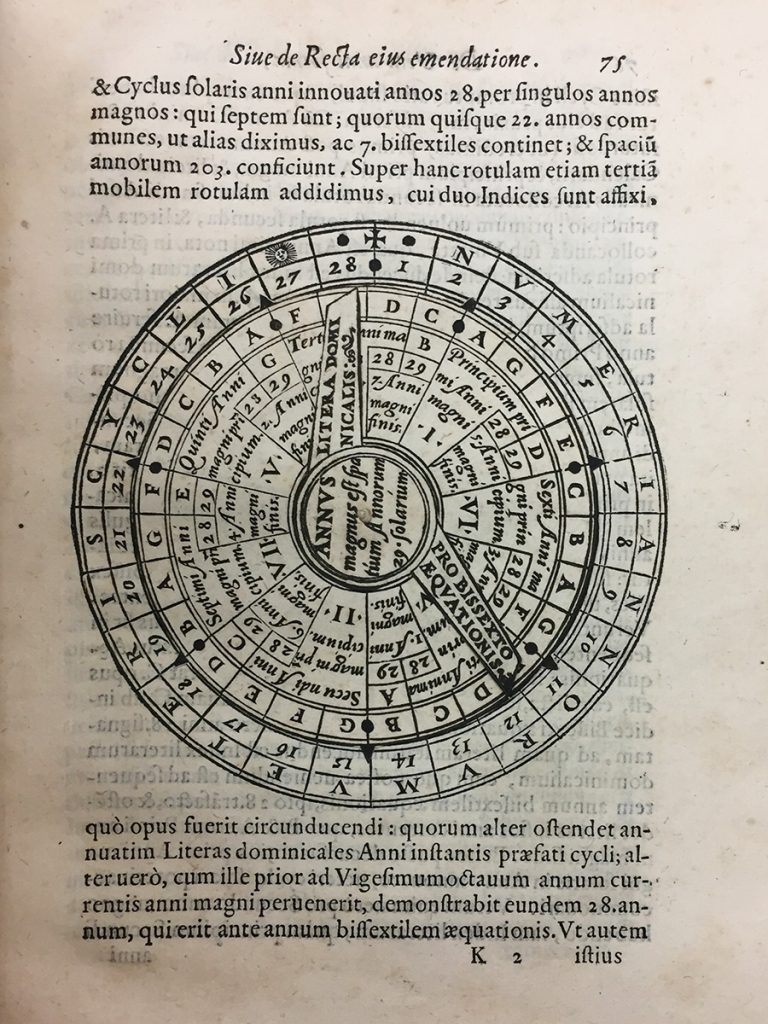

Volvelles show up in other areas of learning, too. Take for example Gioseffo Zarlino’s (1517–1590) work on calendar reform. Best known today as a music theorist and composer, Zarlino published a book for the consideration of Pope Gregory, who was eager to institute a new calendar that would bring Easter back to the time of the year when it had been observed by early Christians. Zarlino’s proposed calendar would not end up being the one Gregory adopted in 1582, but the ingenious volvelle he designed remains an impressive piece of technology. By manipulating the discs, readers can reconcile the 28-year solar cycle of the Julian Calendar with the 203-year cycle that his book proposes. (Zarlino subdivides his solar cycle into seven 29-year periods, or “Great Years.” A solar cycle is the number of years before days of the week will recur on the same days of month.)

Such objects are not only beautiful. In its own way, each underscores the intimate relationship between new forms of knowledge and media design. Design communicates knowledge, yes, but it also creates it.

This article is revised and updated from a piece originally published in the online Ransom Center Magazine in January 2018.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.