By Alejandra C. Garza, Ph.D. candidate, AHA Career Diversity Fellow 2018-2020

This is the fifth post in a wider series, Navigating the PhD and Beyond: Lessons from the AHA Career Diversity Initiative. The series is presented and curated by Alejandra Garza as part of the AHA Career Diversity for Historians Initiative. As the 2018-20 graduate student fellow, Alejandra’s goal was to show graduate students and professors that the skills developed in a PhD program “are applicable no matter what we do when we leave”. Here Alejandra interviews Dr. Brian Stauffer. He received his Ph.D. in 2015 with a dissertation entitled, “Victory on Earth or in Heaven: Religion, Reform, and Rebellion in Michoacán, Mexico, 1869-1877,” supervised by Dr. Matthew Butler. He is currently a Spanish Translator at the Texas General Land Office.

What motivated you to enter a PhD program? Did your motivations change over the course of the program?

I entered the PhD program in Latin American History at UT Austin in the fall of 2009, after receiving an M.A. from the University of New Mexico. At the time, this felt like my adult life finally falling into place, since it seemed like a sure bet that a PhD in Latin American History from UT would yield a solid tenure-track outcome. And the truth is that it could have. The Latin American History program provided first-rate training: excellent faculty, access to the bibliographic and archival riches of the Benson Library, funding for archival research abroad, support for professional development, etc. Ph.D.s who graduate from the History Department have a strong record of earning good jobs, even as the profession as a whole has continued its decline. The problem is that despite all of this, many other well-deserving students at UT, and untold others outside it, are being left out or asked to endure exploitative and precarious placements until some brighter horizon appears. I decided I couldn’t do that.

What was your experience with the initial entry into the job market?

I entered the job market in 2014, during my write-up year, and received no interview requests. In 2015, during a much-needed and much-appreciated postdoctoral year at UT’s Institute for Historical Studies, I applied for dozens of jobs and was invited to phone interviews for two of them. Ultimately, I scored an on-campus interview once and received a single job offer from the same institution. Conventional wisdom says I should have taken that job—low salary, high living costs, grueling teaching load, and utter lack of research support and all—and waited for my chance to jump to something more desirable. But I have a partner and kids, and frankly I wasn’t sure my family would withstand any more instability and penury. So, I made the hardest decision of my life and declined the offer without any other prospects, and I began looking for non-academic jobs in Austin—where my kids had school and friends and some semblance of a life.

How did you end up in the career you currently have?

I applied for dozens of non-faculty jobs—school districts, libraries, non-profits, state agencies, etc. And even though I mostly got rejected by this market, too, the process itself was so much easier that it didn’t feel nearly as soul-crushing as the faculty job market. I was invited to interview at two different state agencies (the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board and the Texas General Land Office) before I had even technically finished my postdoctoral stint in the summer of 2016. Both places offered me the job, with the result that a small bidding war ensued. In fact, both initial salary offers were better than the one offered by my sole university suitor that year.

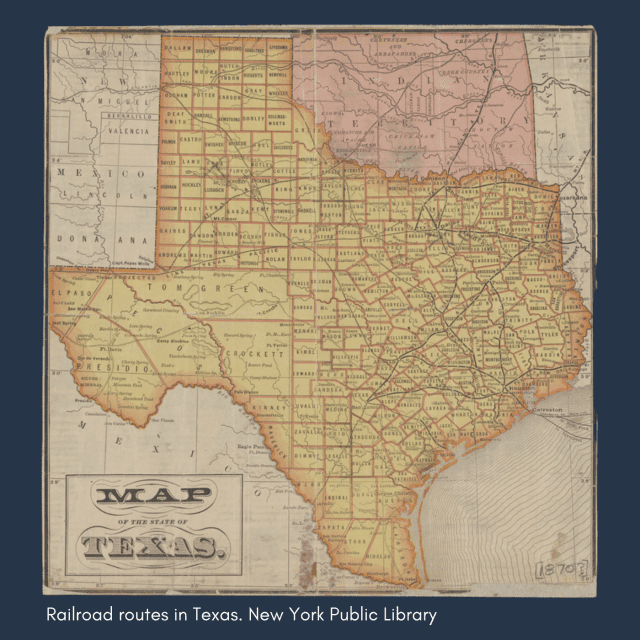

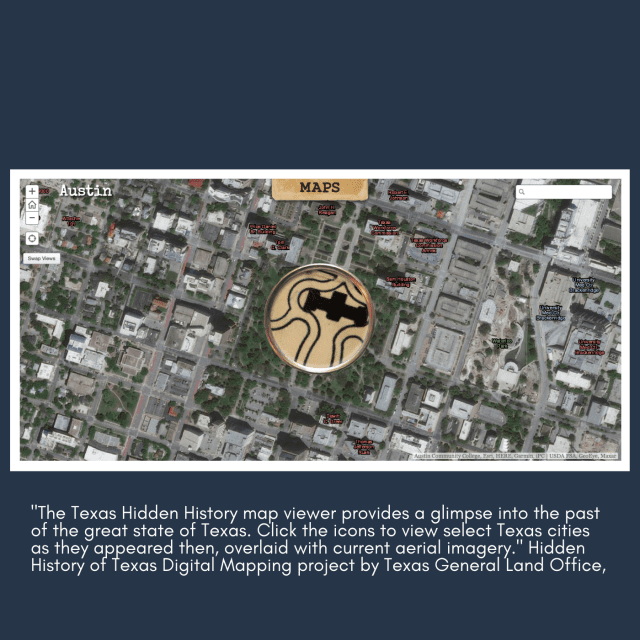

Ultimately, I chose the Texas General Land Office, where I work in the Archives and Records program, because it offered me a crucial link to the discipline of History. And, yes, because they offered me a better salary. My job, which combines the roles of a translator, reference archivist, curator, and historian, is frequently rewarding on its own terms but has also allowed me to continue publishing and engaging in academic circles. Since it also requires no teaching and features few of the pressures of a faculty role, this is perhaps a better outcome than I could have imagined back in 2009 when I started this journey. Like most people in humanities doctoral programs, I had come to graduate school hoping it’d lead to a fulfilling career of researching, writing, discussing, and teaching about history. What I didn’t understand then is that I didn’t have to be a tenured professor to do that.

If COVID-19 has impacted or even taken your job in these difficult months, please share that with us, too.

Of course, the job is far from perfect: it comes with its own unique challenges, and there are limits on the kind intellectual work I can do. But on the whole I am very content, and since the COVID 19 crisis has not threatened my job, I count myself very fortunate to have it.

What do you wish you had learned in graduate school?

I suppose I mostly wish I could have been comfortable exploring non-faculty employment without shame. I get the feeling that the culture of shame is no longer the problem it was in my graduate years, and I’m thrilled to see History Department leadership taking a more proactive role in helping students obtain (paid) internships outside the university, such as the one I directed at the GLO in 2018 and 2019 (COVID killed this year’s internship but we hope it’ll return in the future). Incidentally, those former GLO interns are both UT alumni who are now off to incredible new jobs, one inside and one outside the academy. Of course, the internship wasn’t everything—they benefitted from the same excellent UT training as the rest of us and have loads of talent of their own. But, as I hope either of them could attest, internships are a really crucial way to develop skills and relationships that lead in new directions, especially for folks thinking of exiting academia. Funding and approval pending, I hope to see more UT doctoral students apply for internships at the GLO in the future.

Any other advice you have for new PhDs entering the job market?

PhD students entering the academic market today have only ever known crisis. Like me, many started on this path as a way to escape the post-2008 economic collapse, which rendered the undergraduate degree an insufficient guarantee against poverty. Today, they are graduating into a much worse calamity. In between collapses, moreover, long-running neoliberal restructuring and its attendant adjunctification meant that even the market’s “good years” were lean years, even for students from excellent programs like UT’s. The present moment is particularly bad, but things haven’t been good in a long time, successful UT placements notwithstanding.

I say this not to foster despair but to encourage you cast aside any shame you might be feeling about the possibility—or even certainty—of not finding an academic job this year. This is not your fault.

This is perhaps of little comfort, but your knowledge and skills and labor are inherently valuable even if the Job Market in its infallible wisdom has decided not to remunerate them. More comfortingly, I can assure those of you that leave the profession that there are institutions outside the academy that will see your value. I will admit to feeling somewhat bitter and ashamed when I left academia in 2016, but now I feel mostly gratitude. Mine is happy story, all things considered, and yours can be too, with or without a tenure-track job.

This blog series was created by Alejandra C. Garza with assistance from Dr. Alison Frazier and Dr. Michael Schmidt as part of the AHA Career Diversity for Historians Initiative 2018-2020.

Dr. Brian Stauffer received his Ph.D. in 2015 with his dissertation entitled, “Victory on Earth or in Heaven: Religion, Reform, and Rebellion in Michoacán, Mexico, 1869-1877,” supervised by Dr. Matthew Butler. He is currently a Spanish Translator at the Texas General Land Office.

More in this series:

- My Journey Through Career Diversity by Alejandra Garza

- Navigating the PhD and Beyond: Verónica Martínez-Matsuda

- Navigating the PhD and Beyond: David Conrad

- Navigating the PhD and Beyond: Eric Busch

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.