On Monday evening, September 28, 1970, Egyptian radio and television abruptly began to broadcast recitations of the Quran. It was a familiar sign that something of great significance had gone horribly wrong. Egyptians had heard it before – when they lost the June 1967 war and again, eighteen months earlier, when a beloved Egyptian Chief of Staff died in battle. They had had enough of tragedies. As rumors began to circulate and fear rose, millions braced themselves for the worst as they waited for an official statement. Tens of thousands of people spontaneously took to the streets. Their bond to Gamal Abd al-Nasser ran deep. He had, they believed, given them life with dignity: something their parents could only have dreamt of. They loved him, and they believed in him. And as the radio kept broadcasting, they feared that the news might have something to do with Nasser. Anticipating the worst, some burst into tears. Others collapsed. They worried he had died. They knew he had. And later that evening, a broken and tearful Vice President Anwar al-Sadat appeared on television. Though he tried to say something meaningful, all he managed to say was that “Nasser was greater than words.”

Nasser was no ordinary head of state whose life could be summed up with a quick eulogy. At the height of his power, during the 1960s, he was known in the West mostly as a regional troublemaker, a gangster of sorts and a dangerous dictator. British Prime Minster Anthony Eden called him Hitler (he wasn’t) and others referred to him in the language that in future decades was reserved to depict the likes of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein and Usama Bin Laden. The true Nasser was no saint and certainly no stranger to the deployment of brutal state power against internal enemies, including the Muslim Brotherhood, Marxists, Communists, Liberals, and anyone else who defied him. But to stop at that would be to miss the story of one of the most fascinating, complex and idealistic figures of the twentieth century. The Arab world is used to the unexpected rise and fall of its unelected leaders. They move on quickly. But Nasser’s untimely death at the young age of 54, left them speechless. Five decades later, the painful legacy of Nasser and his movement still unsettles public life.

Nasser was not elected to his post. He was 32 when, along with an inner circle of officers, he seized power, put an end to a monarchy that had lasted from 1805 to 1952, dismissed the political parties, suspended the constitution, and effectively terminated Egypt’s decades-old liberal era. He inherited an exploitative agrarian economy that was in shambles. Replace cotton with sugar and tobacco and it looked much like pre-Castro Cuba. Most of the fertile land was committed to growing cotton, the main export staple and the biggest source of national income. A small group of 2,750 families owned most of this land which they leveraged in order to achieve disproportional political representation. Most Egyptians were landless, illiterate peasants. Working the cotton fields, they lived in a state of barely human existence; a condition that looked in some ways close to slavery with no end in sight. Life expectancy for men was less than 40 years on average. Women did slightly better. Industrialization was slow, inconsistent, and uneven the burgeoning middle class struggled. But beyond being economically vulnerable, the literate middle class struggled to provide an affirmative answer to the identarian question “who are we?” Are we Muslim, Arab, Egyptian or, perhaps, a mélange of all three in no particular order of importance? Should an Arabized version of European culture serve as the basis for communal life or perhaps a modernized Islamic version?

Add to these identarian anxieties the constant British involvement in Egyptian politics and its continued military presence in the country, and you begin to understand the sources of Egypt’s misery and the depth of its cultural pessimism. In all aspects of life, nothing was really working properly. The five governments that rose and fell during the first six months of 1952 alone reflected the collective sense of impasse. Egypt was ready for the coup and when it finally came, six months after the burning of downtown Cairo, nobody fought to defend the passing of its liberal democracy.

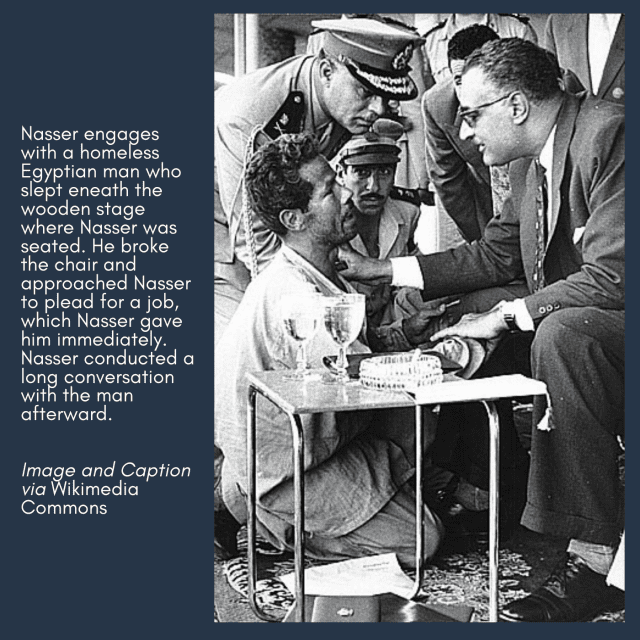

When he came to power, Nasser’s dramatic promise was life with dignity. And he began to design a new social contract to meet this promise. It took close to a decade to emerge but, once it did, Arab Socialism extended education, healthcare and employment opportunities to all sectors of Egyptian society via a program of massive state-lead industrialization. For the first time in their lives, millions of poor, sick, and marginalized citizens had a reasonable chance to improve their lives. But in return, they gave up their political freedom. It was bargain many had no issue with making. Given their wretched state of being under the liberal monarchy, most people had no problem exchanging liberal political rights for dignity. Nasser’s motto, “lift up your head my brother,” was a constant reminder of this new social contract.

However, to think of Nasser in terms of a single policy or reform is to miss the man and his mark on history as an Arab liberator or, in the eyes of fellow Arabs, as a modern-day Saladin; a man whose ideology was himself. Predicated on struggle, sacrifice and faith, Nasser’s bid for self-liberation first announced itself to the world with the audacious 1956 nationalization of the Suez Canal. Denied by the US the financial means of developing his country, Nasser exercised national sovereignty and, via personal and collective sacrifice, delivered a masterclass in self-liberation. Winning the Suez Canal, he further developed a new, modern politics of salvation and, slowly but surely, Nasser emerged as something of a postcolonial Messiah. Nasserism’s emancipatory message traveled as near as Palestine and as far as Latin America.

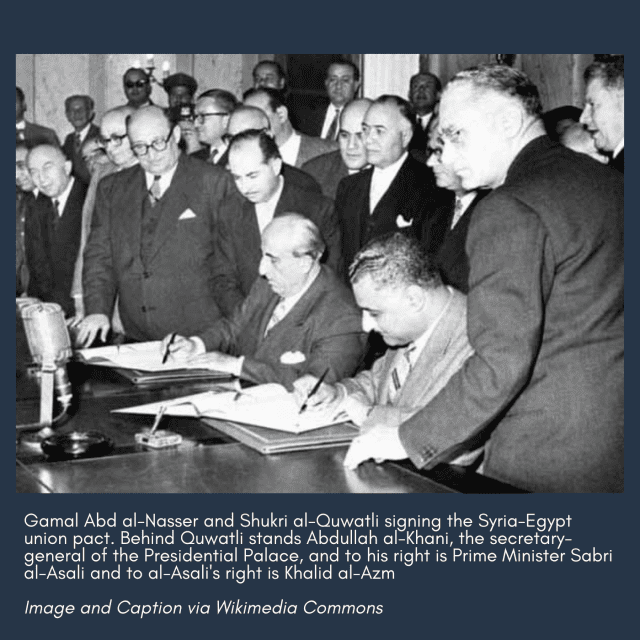

By the early 1960s, Nasser juggled various projects of enormous dimensions and magnitude ranging from ambitious infrastructure projects, including the construction of an enormous hydro-electric dam on the Nile to direct interventions in Cold War conflicts in Africa. Especially ambitious was the plan to unite the Arab world into a single unified state. That plan was meant to undo the post 1918 colonial borders which had fragmented the region and carved it into several unnatural polities, such as Syria and Iraq. Flying high, the banner of Pan-Arabism spoke not only of the mystical power of unity but also of the total transformation of self and country which Nasserism aspired to fulfil. Much of that vision was at play well before the likes of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara came onto the scene and began borrowing freely from Nasser’s political playbook. In fact, in 1958, when the young Che arrived in Cairo to introduce himself, he was met with a disinterested shrug.

The mid 1960s were not kind to the Nasserist project. Egypt got bogged down in an ideological war with Yemenite tribes and their Saudi backers. It resembled America’s Vietnam and Nasser knew it. As it faced the daily bureaucratic troubles of state-building, the pace of achievement and revolutionary momentum slowed down considerably. Most painfully, amidst accusations of Egyptian paternalism, the Syrians abandoned the three-year-old United Arab Republic, thus casting doubt on the entire project of Pan-Arabism. With his reputation damaged, Nasser was in search of a new cause that would once again revitalize the revolution and mobilize millions. It became the liberation of Palestine. It was something of a tall order, as neither Egypt nor its neighbors were truly ready for the effort. However, once proposed, the momentum was unstoppable and, as in the past, the people were once again ready to sacrifice for a worthwhile revolutionary cause. By late May 1967, just a few months before the war, it was unclear if Nasser was leading the masses to war or if was it the other way around. A cold analysis of the facts on the ground should have revealed to Egypt and its allies that the prospects of liberating Palestine were slim indeed.

Three days into the war, as Egyptian radio continued to assure its listeners that the combined forces of Egypt, Jordan and Syria were on their way to Tel Aviv, a shaken Nasser appeared on television and admitted defeat. He began by describing the colossal defeat as a Naksa. Naksa is a medical term that connotes a setback or a relapse. It was the first time that a term that is typically used to describe the human body was used in such context. But the name stuck and since then the ‘67 defeat has been referred to as the Naksa. In what followed, Nasser assumed the sole responsibility for the Naksa and announced his resignation. The people had been with Nasser through thick and thin, in good times and in bad times. And though facing the most devastating and humiliating defeat in living memory, they automatically rejected his resignation. After three days of mass demonstrations, Nasser retracted it. A transcendental figure such as Nasser could die in battle and become a martyr but, just like a Messiah, he could not resign.

We tend to think about the June 1967 war as a short six-day conflict that was over before it even began. Not for Nasser. For him, it lasted for another thousand days, and by the end of it, he was dead. Unknown to the Egyptian people, Nasser was sick. Very sick. Compounded by the stress of the war, his mild case of diabetes spiraled out of control. That was the true Naksa. By 1969 he was diagnosed with hyperinsulinemia, atherosclerosis, moderate obesity, hypercholesterolemia, lipedema, diabetic neuropathy and fibrositis. A heavy smoker, he was in constant pain, and in the midst of a war of attrition with Israel. As the war intensified, he suffered a massive heart attack.

His many doctors kept this Naksa a state secret. The people knew nothing about it but also the Egyptian leadership, his close circle, his family and, initially, even Nasser himself, were kept in the dark. Trying hard to undo the war’s many consequences, Nasser’s last thousand days in power embodied a general collective malaise. Then came the awful September 1970, another stressful month in which Nasser mediated in a bloody conflict between the Palestinian PLO and King Hussein of Jordan. This last assignment to halt an Arab civil war left him dead.

In the days and weeks after Nasser’s shocking and untimely departure, anybody who could write or talk tried to make sense of this immense loss. One poet came close:

He is all of history in one man

He is everything in one thing

He existed from the heart of defeat

And entered the heart of victory

He came from the battle of Hittin and from Dir Yasin…

From here and from there he came to us

Did Abd al-Nasser die?

And still

Freedom will not die

Justice will not die

Unity will not die…

Indeed, under Nasser, the Arab world had experienced the two extreme ends of liberation and bitter defeat. Liberation was meant to deliver the people from a wretched state of barely human existence and constant humiliation. Defeat brought them full circle to once again to experience and re-live the painful sense of humiliation. Admittedly, Nasser’s emancipatory project of self-liberation and radical self-fashioning was in ruins – ruins that the magnetic muse of the revolution, singer Umm Kulthum captured in a song by the same name. In the decades since his death Egypt and the Arab world has changed in profound ways. Arab unity was abandoned as a viable political project and inter-Arab cooperation declined and then almost entirely disappeared. Nasser’s successor, Sadat, signed a peace treaty with Israel, thus leaving the vulnerable Palestinians to deal with Israel on their own. Other Arab states followed this trend. Internally, the Egyptian elite gradually shifted to capitalism, abandoning Nasser’s social contract and leaving the people to the mercy of market forces.

Severing the bond to the people and undermining communal solidarity, the elite reigned through the application of raw power. By the mid 1980s Egypt was a full-fledged security state with no communal vision.

Of equal weight and consequence was the mass cultural shift toward religiosity. With the Nasserist system of state-lead salvation and rebirth defunct, faith-based societal projects formed a parallel state. By the mid-1990s Egypt was a transformed country with seemingly new challenges. And yet, every July 23rd, at the anniversary of the revolution, Egyptians embarked on a ritualistic debate about the legacy of Nasser. They disagreed about much of his record, including his personal responsibility for the 1967 defeat. However, they tended to agree about Nasser’s personal sincerity and about his commitment to improving the life of ordinary people. Mostly, they still shared Nasser’s original understanding of the problem of dignity. And though it seemed as if life with dignity had become a strictly idealistic aspiration, the 2011 revolution and its ubiquitous slogan “Bread, Freedom and Dignity,” as well as the oppressive state response and the military takeover that followed, had Nasser’s name written all over it.

Yoav Di-Capua teaches modern Arab intellectual history at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of Gatekeepers of the Arab Past: Historians and History Writing in Twentieth-Century Egypt (University of California Press, 2009). His new book, No Exit: Arab Existentialism, Jean Paul Sartre and Decolonization, was published by the University Press of Chicago. He is currently writing a new book about sacred politics. His work was supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in Germany