By Jeremi Suri (with comment by Daniel Immerwahr)

From the Editors: This article is accompanied by a comment from Daniel Immerwahr (Northwestern University) who specializes in twentieth-century U.S. history within a global context. Such comments are a new feature for Not Even Past designed to provide different ways to engage with important new work.

One problem with arguments that bemoan or cheer the end of the “American Century” is that there never was one. Despite the United States’ moment of economic and atomic predominance after World War II, the United States immediately faced strategic challenges from the Soviet Union, and soon from Communist China, among others. If anything, American citizens felt less safe from foreign adversaries in 1945 than they had a decade earlier.

The Cold War meant that deadly conflict continued. Five years after the Japanese surrender at Tokyo Bay, American soldiers were again in combat in Asia. Between 1950 and 1953 more than 33,000 Americans died on the Korean Peninsula, which remained divided near where the conflict had started. Hostile, aggressive governments in North Korea, China, and North Vietnam redoubled their efforts to undermine U.S. interests, especially around Japan. U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy frightened a majority of Americans into believing that communists were infiltrating all aspects of domestic society. Some American Century.

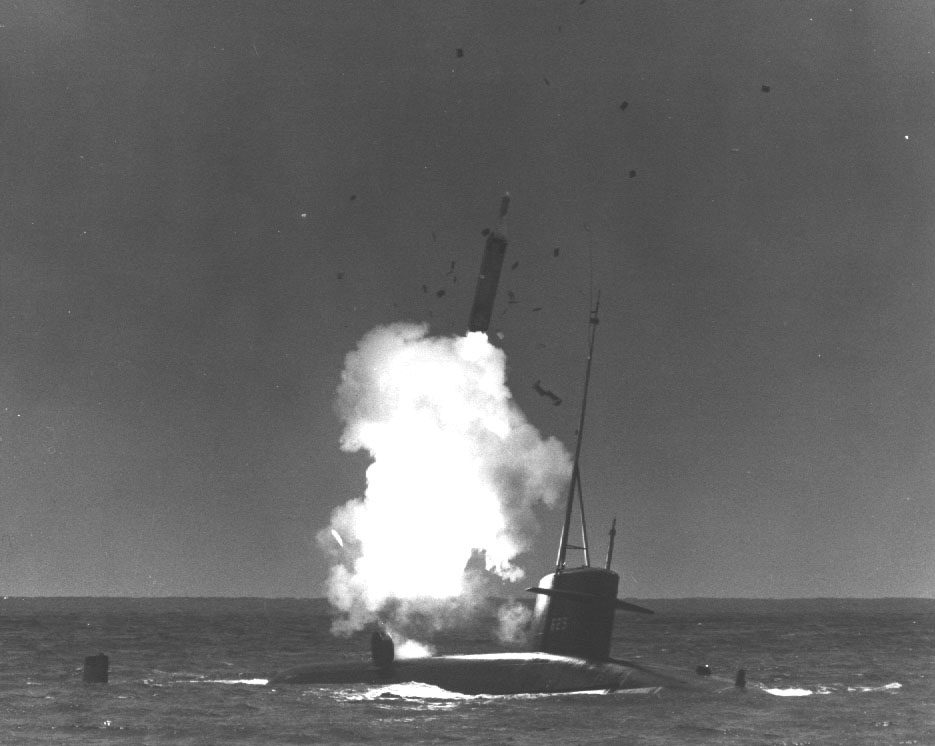

The reality is that, throughout the Cold War, American military power rarely produced the battlefield dominance that leaders and citizens expected. More often than not, American soldiers and their proxies fought to a standstill against smaller, determined adversaries in Korea, Lebanon, Cuba, Vietnam, Angola, and elsewhere. Similarly, generous foreign aid rarely gave U.S. leaders the leverage they wanted. Cold War historians have chronicled in detail how allies from Paris and Bonn to Tokyo, Tehran, and Tel Aviv resisted and manipulated Washington while benefiting from American protection, markets, and resources. The allies realized that the United States needed them, and they could play to a mix of fears, hopes, and hubris among American leaders. There was always a threatening adversary to justify continuing to send aid to allies, despite their resistance to Washington’s demands for reform and loyalty. Very often, smaller partners pulled the United States into projects and conflicts that did not serve American interests. Vietnam, a former French colony, was the most infamous of many examples.

Washington’s international leadership was always limited, uncertain, and contested. It was most effective when it facilitated cooperation, often among a diverse group of allies and former adversaries. In Western Europe, the United States helped to build institutions for economic integration and collective security through the Marshall Plan, the European Coal and Steel Community (later the Common Market and the European Union), and NATO. In East Asia, Washington nurtured economic development, trade, and security cooperation among Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. On a more global scale, the United States helped create the United Nations and its associated agencies that constructed webs of technical and political cooperation across issues from atomic energy and peacekeeping to health, education, and communications. Through the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, also U.S.-led institutions, the United States helped to bring numerous countries together to address global poverty and economic instability.

Postwar internationalism served American interests by making the world safer and more stable—for the prosperity of U.S. citizens, as well as many others. American diplomacy and foreign assistance supported alternatives to communism, war, and depression. Every high-ranking American foreign-policy maker before 1980 remembered how the isolated and conflictual environment before World War II contributed to that cataclysm. These chastened officials—Democrats and Republicans —sought to prevent a recurrence, in a nuclear age, at almost all costs. “Never again” did not mean the United States had to dominate the world; it could not. “Never again” meant the United States must lead a diverse group of nations to work together toward common interests.

This postwar commitment to international engagement and cooperation had many flaws. It was intolerant of communist and many nationalist alternatives. It presumed Western, and especially American, superiority. And it gave disproportionate voice to figures (“the establishment”) with access to capital, prestigious institutions, and specialized knowledge. Many voices, at home and abroad, were locked out of U.S. policy discussions. Despite incessant claims about democratization, American postwar leadership often encouraged a kind of fraternal cooperation among like-minded trans-Atlantic figures who fit the stereotypical descriptor “pale, male, and Yale.”

These serious limitations notwithstanding, American leadership in the second half of the 20th century still worked because it brought numerous countries together to cooperate on improving the lives of their citizens. Instead of war, societies that allied with the United States increased their trade and consumption. Many allies, especially in Europe and East Asia, became more open and democratic. Others, especially in the Middle East and Latin America, remained repressive, but they also had to grapple with rising calls for reform, openness, and human rights that the United States legitimized, even if it did not always support them in practice. Frequently, U.S.-supported institutions, especially the United Nations, promoted national independence and human rights, despite Washington’s own abandonment of those priorities.

The postwar international ecosystem seeded by U.S. leadership made repression harder to justify or ignore, and American realists did not control the narrative. American claims about freedom and justice abroad reverberated at home, fueling civil rights activism and forcing Jim Crow Cold Warriors on the defensive.

The infrastructure that grew around this ecosystem was both American and global at the same time, giving Washington unique influence, but not full control. That was the genius of the postwar international order. The emergence of a dollar-based global financial regime is a perfect example. From the earliest postwar years, American printed currency lubricated commerce in the most vibrant economies. By the end of the 20th century, international finance was denominated almost entirely in dollars, depending on the ability of the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve to both circulate sufficient money, especially during crises, and prevent inflation from spending and borrowing excesses. This delicate balance required cooperation between the printers of the currency in Washington, the bankers around the world, and the governing powers in large economies.

The great and enduring success of American leadership was to manage this process, even when the circulation of dollars created new competitors, including Japan and then China. Americans were better served by a global capitalist system they could help regulate, but not control, rather than the alternatives. Although U.S. policy in recent years has undermined postwar internationalism—and also faced renewed challenges from foreign rivals—real American leadership remains vital. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrates how essential international cooperation is for monitoring threats, managing supply chains, serving suffering populations, and stimulating weakened economies. The pandemic has become more contagious and deadly, particularly in the United States, because American-led international cooperation has been lacking. And the countries that have managed well on their own will still suffer from the pandemic’s deepening damage to the U.S. and world economies.

No other country has the resources, networks, and history to support cooperation on the scale of the United States. American leaders, because of their global media presence, frequently set the tone for interactions between societies. It is simply impossible to imagine the core foundations for international cooperation holding around economy, science, health, and environment without contemporary U.S. leadership. There’s no other country that could step forward and stand up effectively against destructive actors.

All international orders have a life cycle. They rise and fall, but they do not disappear overnight. The American postwar international order has long shown signs of decline, identified by Henry Kissinger and others more than 50 years ago. Until there is a viable replacement, Americans and the plurality of nations would be wise to continue to support U.S. leadership in bringing openness and stability to a very dangerous, conflict ridden world. One country cannot guarantee security and justice, but someone must lead.

Debates about renewing or abandoning the pretenses of a mythical “American Century” are distractions. The real work is in renewing the cooperative American international leadership that insured so much peace and prosperity for 70 years.

A version of this article first appeared in Foreign Policy. It has been revised since then and a comment added.

Jeremi Suri holds the Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. He is a professor in the University’s Department of History and the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs.

Daniel Immerwahr (Ph.D., Berkeley, 2011) is an associate professor at Northwestern University, specializing in twentieth-century U.S. history within a global context. His first book, Thinking Small (Harvard, 2015), offers a critical account of grassroots development campaigns launched by the United States at home and abroad. His second book, How to Hide an Empire (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), tells the history of the United States with its overseas territory included in the story.