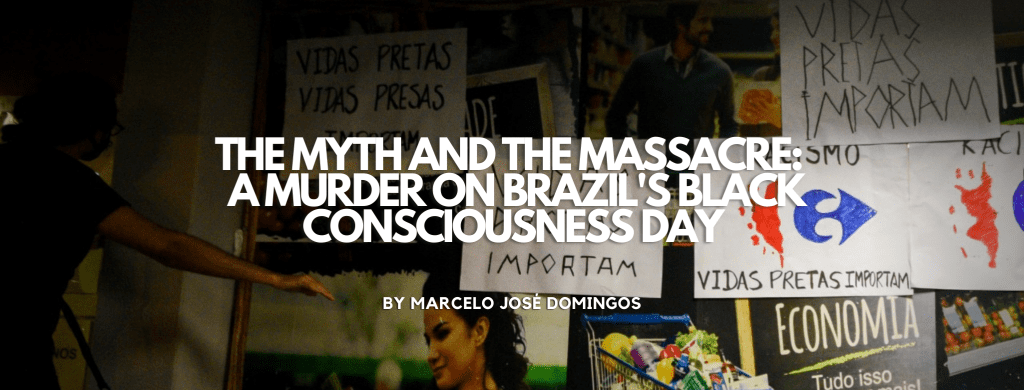

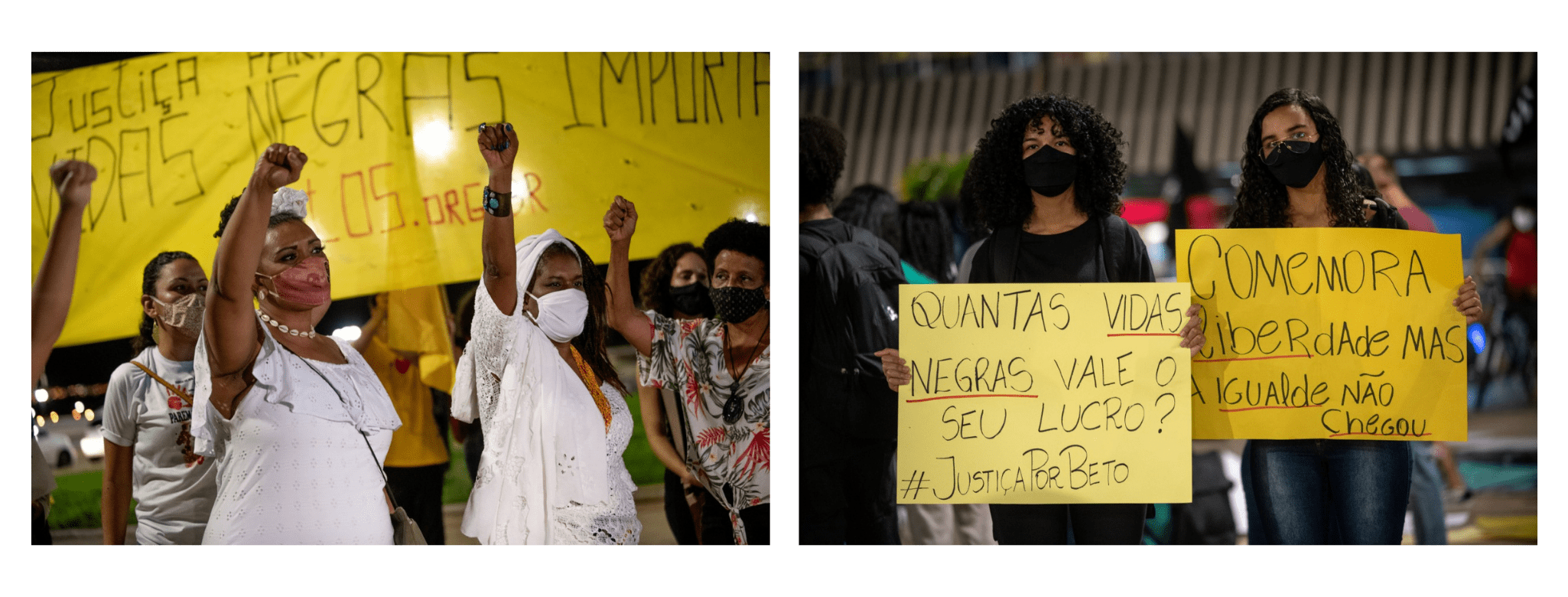

Brazil’s Black Consciousness Day (November 20th) was traumatic in 2020. Amid the devastating effects of COVID-19, in which more than 169,000 people have died, Brazilian citizens awoke to news of a racially-motivated murder. João Alberto Silveira Freitas, a 40 year old Black man, went to a supermarket with his wife in Porto Alegre, the capital of Rio Grande do Sul state. After a not-so-clear dispute involving Freitas and the security officers at the cashier, he was ”invited” to leave the grocery store. While his wife was paying the bill, Freitas was beaten to death by security guards. This heinous incident was recorded, and then disseminated on social media. The news of his death was released on the date officially recognized by Brazil to commemorate Afro-Brazilians’ historical struggle against slavery and racism.

In a press interview, Brazilian Vice President General Hamilton Mourão, categorically condemned as ”regrettable” Freitas’s death at the hands of the security guards. But he went further, stating: ”For me, in Brazil there is no racism. This is something they want to import here to Brazil. It doesn’t exist here.”[1]

The Vice President’s statement might sound like nonsense today, especially for black activists, given the extensive data showing Black Brazilians discriminatory treatment in employment, housing, education, and by law enforcement. Yet such a conviction is disturbingly consistent with the historic rhetoric of the Brazilian armed forces and conservative sectors regarding the nation’s race relations during the civil-military dictatorship that ruled the country between 1964 and 1985. The recently declassified intelligence Army reports of Black Movement activism in Brazil are the most valuable source for this discussion.

During the so-called decompression period (1974 – 1985) of controlled democratization, the Brazilian dictatorship gradually relaxed authoritarian rule. Simultaneously, new political and social organizations – such as unions, student and grassroots associations, and the modern Black movement initiated their activities. Its leading anti-racism group, the Movimento Negro Unificado Contra a Discriminação Racial – later renamed simply Movimento Negro Unificado[2] – MNU, was founded in 1978 in the city of São Paulo. Given its connections with emerging leftist factions, the MNU, since its inception, had its activities monitored by the repression intelligence.

The origins of the November 20 commemoration as Black Consciousness Day date back to the same decade. At that time in Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Bahia, groups of Black intellectuals met to discuss Brazil’s racial inequalities. In 1978 these groups would form the coalition of the MNU. Among the various ideas and proposals for action and discussion, activists rejected two broadly accepted beliefs among Brazilians. The first was the concept of the so-called Brazilian racial democracy. This term is attributed to Brazilian anthropologist Gilberto Freyre (1900 – 1987), originating from his seminal book Masters and Slaves (1933). Freyre advocates the idea that Brazilian society’s formation, based on racial mixture, was a harmonious process.

The work of sociologists Florestan Fernandes and Roger Bastide, Brancos e Negros em São Paulo (1959) The Negro in Brazilian Society (1969) however, dismantled the ‘myth’ of racial democracy. Subsequently, other authors, such as Lélia Gonzalez and Carlos Alberto Hasenbalg, to name just a few, did the same. Black activists also sought to revisit the historical memory of slavery in Brazil. On May 13, 1888, Princess Isabel de Orleans e Bragança, as acting head of the government, had proclaimed emancipation. Official commemoration of the date reinforced the idea that the freedom of the Black population had been given rather than achieved through their individual and collective effort.

Dates are potent ingredients for the production of myths. The selection of November 20 was a response of Brazilian black activism to official history. Activists sought out the colonial past of Brazil for inspiration. At that time, the enslaved who fled their owners created communities of resistance and struggle called quilombos. The largest and most powerful of them, Palmares, lasted almost 100 years. After several attacks by the colonial forces, it was destroyed by mercenaries on November 20th, 1695. Its leader, Zumbi, was executed that same day. This date was chosen by activists to become Black Consciousness day, almost 300 years later.

During the 1970s , military intelligence reports targeted Black intellectuals and activists who denounced racism. They were accused of introducing “subversive” foreign ideas to Brazil from the Black Power movement in the United States. Those intellectuals were a permanent threat to the country’s image of racial democracy. Abdias Nascimento (1914 – 2011) was the most notorious example. The Brazilian Black activist was a political exile and professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo in the 1970s. One of his most important books, Brazil Mixture or Massacre? Essays in the Genocide of a Black People (1979), denounces the falsehood of racial democracy, and the Brazilian state’s attempt to omit racial data from the national census. As Nascimento writes:

The fact is that since 1950 race and color data have been omitted from census information in Brazil on the assumption that an act of ‘white magic’ can eliminate ethnicity by decree. This process occurs under the rationale that it is founded on a perfect social justice system – everyone is Brazilian, be he black, white, Indian or Asian. But its real significance is that it provides another instrument of social control.[3]

Such frank discussions of racial inequality promoted by Nascimento were categorized as “racist” and subversive by government agents of repression. And the same strategy of demonization would be employed against other Black activists who questioned the dogma of racial democracy. According to Article 33 of the Decree-Law 314 of 1967 – the National Security Law that was based on the National Security Doctrine – incitement of hatred or discrimination based on race was defined as a crime. According to this logic, Black activists or organizations that denounced acts of racism could be deemed in violation of the law.

During the 1980s, Army reports insisted that racism was alien to Brazil. Regarding Black activist groups, for instance, Special Information Report #04 drafted by General Mario Orlando Ribeiro Sampaio, head of Army’s Information Center (CIE), stated in 1982:

CIE intends, however, with this Report, to warn of the danger represented by the deliberate and criminal intention of stimulating the growth in the country, by all means, of moral cancer that is racial discrimination and the stupid antagonism between brothers of different skins. Among the disintegrating ideas that have been occurring to subversives of all shades, (…), There is the idea of stimulating the racial problem, creating it even where it doesn’t exist (…), [These subversives] They will not get their intention, as long as we are attentive to their intentions.4

Note that the author insists on the absence of racial antagonisms in Brazil and suggests that movements like the MNU and other “subversive” groups create such divisions. To the Army officials, the idea of racial democracy was an ideology shared by all of Brazilian society. Those who question such orthodoxies must necessarily be deemed “foreigners.” During military rule, the Brazilian government went so far as to exclude the category of race from the national census of 1970.

As Vice President Mourão’s statement reveals, many Brazilians seem to think the same way about race relations decades later. General Mourão is part of the Brazilian population that romanticizes social harmony and views countervailing beliefs as subversive or foreign to Brazilian culture. Likewise, President Jair Bolsonaro, who also attended military academies in the 1970s, champions an ideology that denies racism and race-based inequalities in Brazil.

Historically, racism in Brazil has not been legally-sanctioned or discursively explicit, but it can be observed in statistics on education, health, and job employment, as well as life expectancy. Today, the numbers are undeniable: more than 50,000 people die violently in Brazil in a country without wars, and the majority are Black males under thirty.[5] João Alberto Silveira Freitas, in this sense, was already a survivor of systemic racial violence and social exclusion until he met his death at the hands of security guards while buying groceries. Despite such grim numbers, however, conservative groups have sustained and defended a lasting idea of racial democracy that far outlived Brazil’s military dictatorship. For those reasons, the Vice President’s proclamation of the absence of racism in Brazil, on the occasion of a Black man’s murder on the Day of Black National Consciousness, is both unforgivable but also sadly entirely predictable.

Marcelo José Domingos is a PhD candidate and fellow at Center for the Studies of Race and Democracy. His work in progress, City, Repression and Resistance: Recovering the Narratives of Black Activism in Brasilia-DF (1978-1988) analyses the Dictatorship intelligence files on the anti-racism struggle in Brazil’s capital.

[1] https://g1.globo.com/politica/noticia/2020/11/20/mourao-lamenta-assassinato-de-homem-negro-em-mercado-mas-diz-que-no-brasil-nao-existe-racismo.ghtml accessed in 11/20/20

[2] Black Unified Movement against the Racial Prejudice and after simply Black Unified Movement.

[3] Nascimento, 1979, 79-80

[4] Arquivo Nacional. BR_DFANBSB_V8_MIC_GNC_AAA_86059514_d0001de0001.pdf

[5] .https://www.ipea.gov.br/atlasviolencia/arquivos/artigos/3519-atlasdaviolencia2020completo.pdf acessed in 11/22/20