As part of IHS Climate in Context, Not Even Past is delighted to partner with Planet Texas 2050. Together we’ll publish a series of posts and articles designed to introduce the Planet Texas 2050 project with a particular focus on how historians and archaeologists are contributing to it.

There was once a town called Myous, on the coast of what is now Turkey. It was a Greek town near the mouth of the Maeander River, under the control of the much larger city Miletus. The ancient travel writer Pausanias tells us that an inlet of the Mediterranean initially gave it access to the sea. But he goes on to explain that the river shifted its course and silted up the opening of the inlet. The resulting stagnant lagoon bred so many biting insects that all the residents of Myous simply picked up and moved to Miletus, leaving only a marble temple of Dionysus as a testament to the town’s better days.

I heard this story from geoarchaeologist Helmut Brückner in the summer of 2018, while he was visiting the Greek site of Histria in Romania, where I had recently begun a joint Romanian-American archaeological project. Brückner, whose work on coastal change is legendary, had come with a geography field school from the University of Cologne. He and his students were collecting soil cores to try to understand the development of Histria’s harbor over time.

When it was established in the 7th century BC, Histria offered an excellent harbor and easy access to the interior of the Balkans via the Danube River. But now we’re not even sure exactly where that harbor should be located. The site has been abandoned since the 7th century AD, and it’s nearly five miles from the sea as the crow flies — behind a stagnant coastal lagoon that breeds vicious mosquitoes.

A Growing Threat

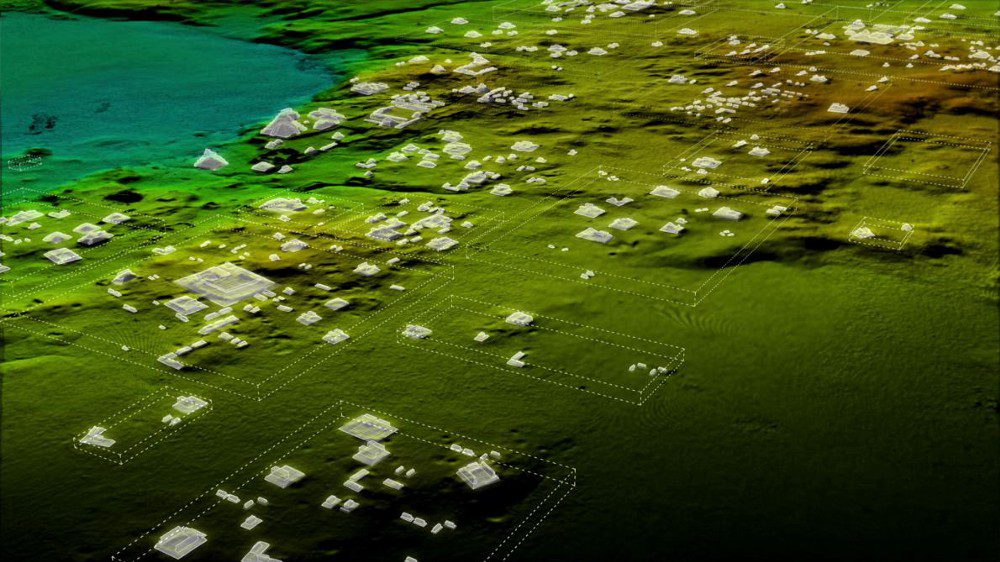

Both the old world and the new are littered with such ruined cities and towns — they’re bread and butter for archaeologists like me. Sometimes they’re as small as Myous; sometimes they’re as large as the densely urbanized Maya landscape LiDAR has revealed under the jungles of Guatemala. In Western Massachusetts, where I grew up, we’d peer into the water of the Quabbin Reservoir to look for traces of towns drowned in 1939 to meet Boston’s growing water needs.

I tend to take their presence for granted. But occasionally, I am sharply reminded of their implications for the challenges that face us today.

An IPCC report released in 2018 suggests that climate change will affect us sooner and more dramatically than we expected: a 2.7-degree Fahrenheit average increase in temperature by 2040 — the more optimistic trajectory, if we take action immediately — could still bring droughts, fires, loss of coral, and increased coastal flooding due to sea-level rise and extreme weather. That last development would threaten many of the world’s major urban centers, which — like the ancient trading cities before them — are frequently oriented to the sea. The vibrant city of Miami, for example, contains by some estimates more than a quarter of the homes at risk for rising sea levels in the United States.

Where Would We Go?

In the past, changes in sea level, droughts, erosion or sedimentation, or flooding (an alternate explanation offered for the abandonment of Myous by the Roman author Vitruvius), have led to the abandonment of settlements. Those ruined towns and cities bear witness to environmental changes that left them unsustainable.

But the people who lived in them didn’t simply die or vanish. They moved. We can read this movement in the old settlements scattered across the landscape, but we can also read it in our own DNA, equally dotted with the evidence for past migrations.

For all of our history, mobility has helped to ensure our species’ success. If the mosquito problem in our neighborhood was too much to bear, we left. But as more and more of the world’s population lives in cities, as more and more of our infrastructure and wealth is invested in those cities, and as our national borders harden in response to population movements driven by the ancient impulse to flee from danger, this option is increasingly fraught with conflict and risk. It also highlights inequities in the effects of climate change, as disproportionately-affected poorer communities are forced to choose between the abandonment of traditional ways of life or staying in harm’s way.

As part of the Planet Texas 2050 Grand Challenge, I have sought to find ways to bridge the divide between the distant past and the present, and to show how previous human experience is relevant to our future. The new flagship project I help lead, Stories of Ancient Resilience, focuses in particular on the ways complex societies in the past responded to climate change and pressures on shared resources like water — issues that today’s cities are also grappling with. As my colleagues and I seek to understand the reaction of past urban communities to environmental stresses through archaeological investigation, I am increasingly struck by the role mobility played in that response. How will we adjust to similar stresses in a world where the vast majority of people can no longer simply pick up and move?

Adam Rabinowitz is an associate professor of classics and is the assistant director of the Institute of Classical Archaeology at The University of Texas at Austin. He is also a founding Planet Texas 2050 grand challenge researcher. His work focuses on understanding how climate and environmental change affected past civilizations and applying those lessons to urban areas today.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.