By Jan Machielsen

This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

In 1603, a thirteen-year old boy called Jean Grenier from La Roche-Chalais, a small barony in France’s Dordogne region, stubbornly confessed that he was a werewolf. The young shepherd boy’s troubles had begun in May when he encountered three female cowherds who were discussing the latest wolf attacks in the region. One wolf had taken an infant out of its crib and eaten it behind a hedge, while one of the girls, thirteen-year-old Marguerite Poirier, had also been attacked while out with her cows. She still had the scars to prove it. The boy, who was widely considered slow and small for his age, approached the teenagers, asking them who was the most beautiful: “because (he said) I want to marry her, so if it is you, I want to marry you.” Finding himself ignored by the three girls, he inserted himself into their original topic of conversation, declaring that he was afraid of no wolves. When he was disbelieved, the boy doubled down on his boasts, again, and again, until he claimed to have been a werewolf himself. “Boys and girls,” the clearly underfed Grenier declared, “were much more pleasant and delicate to eat.”

Given the widespread climate of fear, it did not take the cowherds long to report the teen wolf to the local authorities. Grenier was found and arrested, and he quickly confessed to lycanthropy. Convicted by the local court, the case was swiftly sent up to the Bordeaux Parlement, the region’s appeals court, for review. There the boy’s insistence that he was a werewolf had everyone flummoxed. Two physicians examined him but came to differing conclusions. They both judged him “melancholic” or mentally ill, but one saw evidence of a devil’s mark and witchcraft as well. The judges, too, could not make up their minds. Some supported a death sentence based on the boy’s confession, others could not believe he was telling the truth. It is at this crucial junction that we should turn to the Harry Ransom Center’s Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts 230. It contains the mysterious text that appears to have settled Grenier’s fate.

We probably know more about the Grenier trial than about any other case that came before the Bordeaux Parlement in its long and illustrious history. The palace that housed the Parlement went up in flames in the early eighteenth century, taking its records with it. The teen wolf case, however, was sensational enough that three separate attempts to excerpt or summarize it were made shortly after the trial’s conclusion. In a 2019 article, I showed that we could learn a lot more about the trial and Grenier’s confession when we collated these three accounts, as each offers different but complementary details. Crucially, MEM MSS 230 was not one of these three versions—in fact, I was not even aware of its existence at the time. While it offers few details on the Grenier trial itself (and does not mention him by name), its study can help us examine outstanding issues about the authorship of the other accounts and reconsider a mystery about the sentence that the Bordeaux Parlement pronounced.

The most extensive account of the Grenier trial is contained in a manuscript that belongs to the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. MS Français 13346 is described as containing Mélanges théologiques, a mix of theological texts. For the most part, they belong to the late seventeenth century. The strangest contribution, though, is earlier and has a lengthy descriptive title (on fol. 279r):

Criminal trial against Jean Grenier accused of witchcraft on which there has been a judgement by the Parlement on 6 September 1603. Mr Filesac has examined the information and has given his opinion in his own hand as follows.

(Procez criminel contre Jean Grenier accusé de sorcellerie sur lequel il y a eu arrest du Parlement le 6 septembre 1603. Mr. Filesac a examiné les informations et donné son avis écrit de sa propre main comme il suit.)

The document does fall neatly into two almost equal parts: a lengthy description of the legal proceedings followed by an opinion on the case at hand and the possibility of lycanthropy, a rather vexed question on both philosophical and theological grounds. Where the first half of the document provides a detailed account of the judicial investigations that led to Grenier’s arrest and conviction in La Roche-Chalais, the second is a rich tapestry of biblical, classical, and patristic sources about werewolves, the imagination, and human-animal transformations.

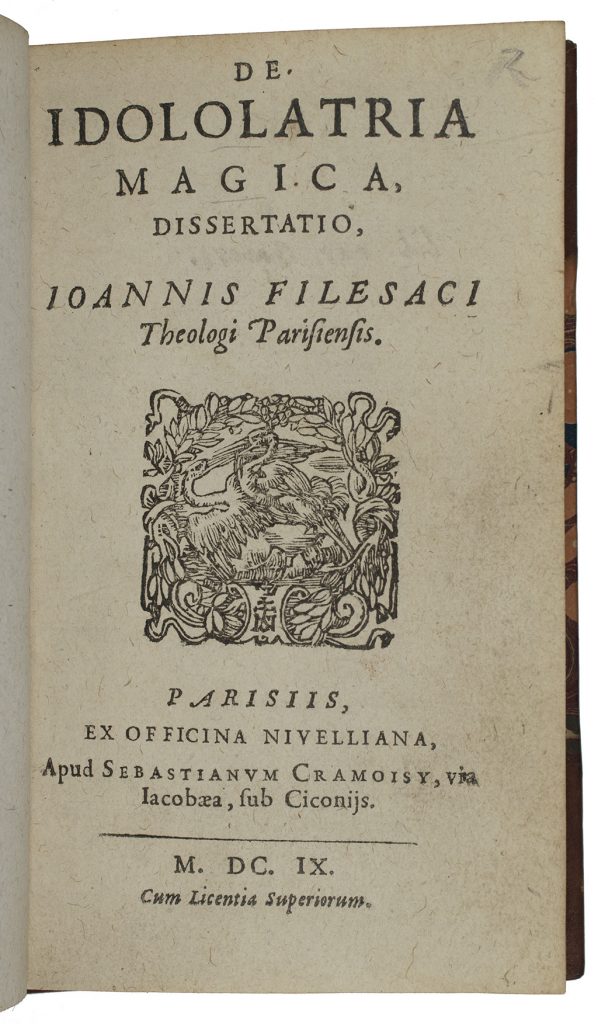

Its purported author, Jean Filesac (1556–1638), was a Sorbonne theologian, who rose to become dean of the Paris theology faculty. Best known for his De idolatria magica dissertatio (Dissertation on magical idolatry, 1609), Filesac would naturally have been interested in the Grenier case. So far, so good, but when we dig deeper, questions appear. How did Filesac obtain an account of the trial? He may have been a logical expert to consult, but there was no tradition of consulting universities in witchcraft matters in France, as existed in Germany at the time. Moreover, if the Bordeaux judges sent Filesac an account of the trial, they evidently did not wait for his response—the manuscript ends abruptly by noting Grenier’s sentence of perpetual confinement in a Bordeaux monastery.

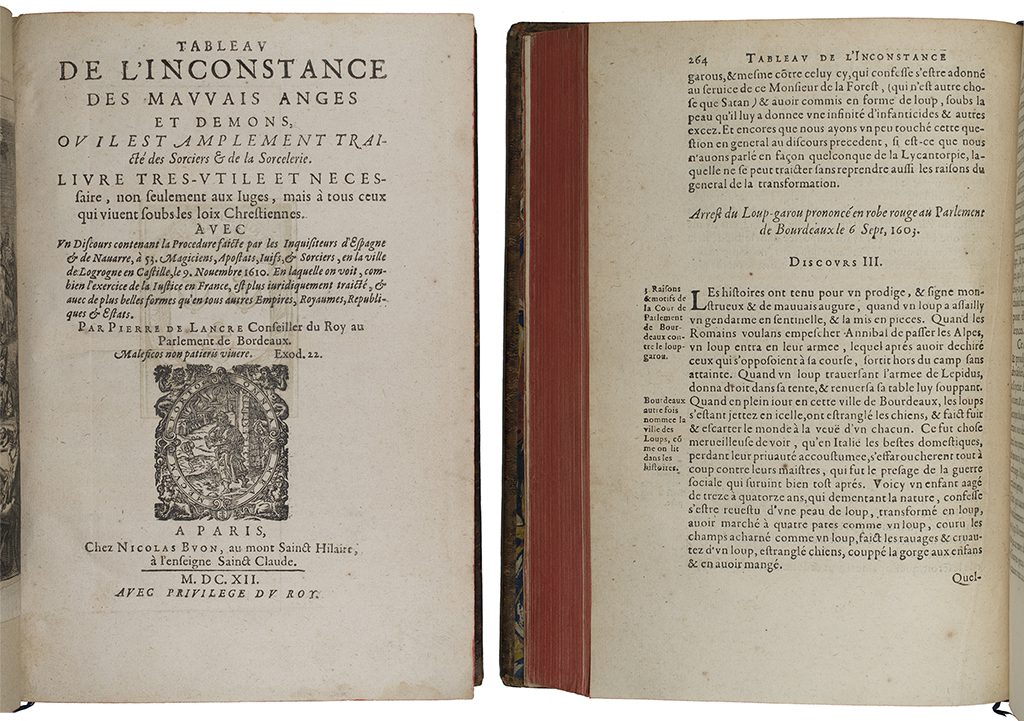

The mystery deepens still further when we turn to a second account of the Grenier case. (The third account of the trial does not concern us here.) In 1612, the Bordeaux judge Pierre de Lancre published his Tableau de l’inconstance des mauvais anges et démons (Tableau of the Inconstancy of Evil Angels and Demons), a work of demonology which devoted one of its six books to the question of lycanthropy. De Lancre was not one of the original judges, but he interviewed the imprisoned Grenier shortly before his death, aged 20 or 21, in 1610. (The reformed werewolf told the judge that he used to prefer the flesh of little girls over boys “because they are more tender.”) As part of his discussion of lycanthropy, de Lancre published the full sentence against Grenier pronounced by the court’s first president Guillaume Daffis on 6 September 1603. What comes next is very odd: this sentence, nearly fifty pages of printed text, is virtually identical to the second half —that is the “opinion” part—of the Filesac manuscript. De Lancre prefaced what he called “the judgment delivered ‘in red robes’ in the Parlement of Bordeaux on 6 September 1603” with excerpts from the original trial proceedings so that the reader may correctly interpret it, so evidently his copy did not contain the first descriptive half of the Paris manuscript. Still, de Lancre’s excerpt matches the second half almost word for word. De Lancre thus presents a question that is beyond perplexing: How did the same text end up circulating under the name of two different authors?

The most straightforward hypothesis was that the Bordeaux judge was mistaken. De Lancre obtained the “sentence” only in 1610 from the Daffis estate after the president had passed away. The judge described the manuscript as a complete mess: “so badly and falsely arranged, as if it had passed through an infinity of different hands, that I could hardly recognize the workman in the work.” It was certainly possible, as I suggested before, that Daffis received Filesac’s opinion sometime before his death and that de Lancre confused it with the sentence the first president had pronounced. I took care not settle the issue. For the purposes of my article—I was principally interested in the trial proceedings and the testimony they offered, not the philosophical and theological debates that followed—it did not matter greatly.

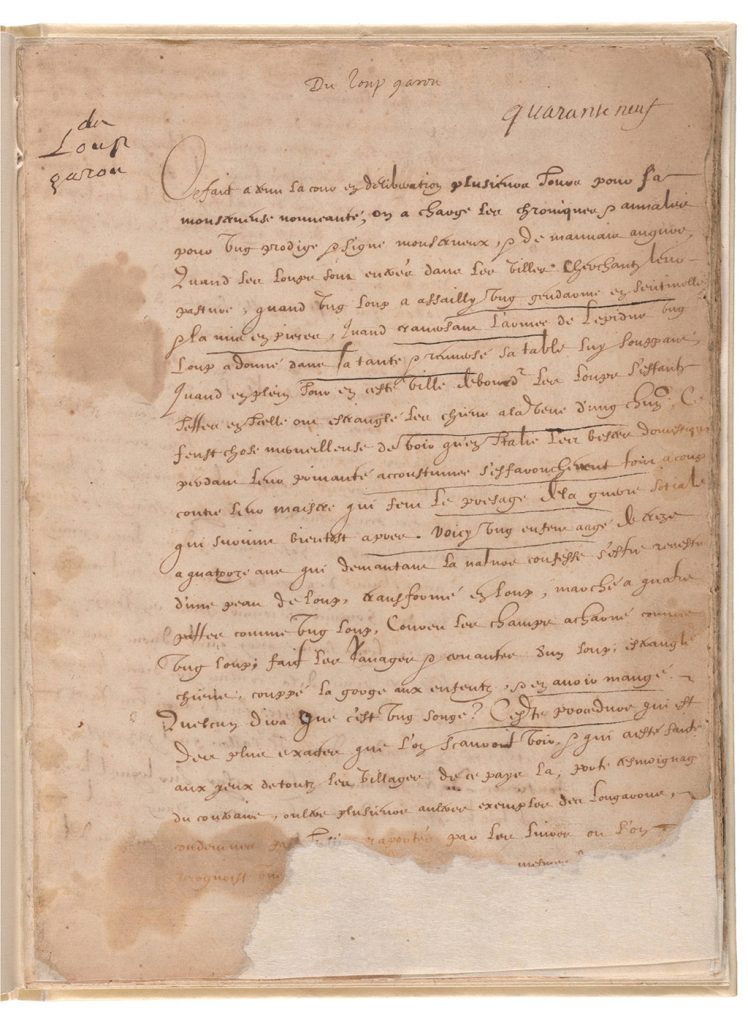

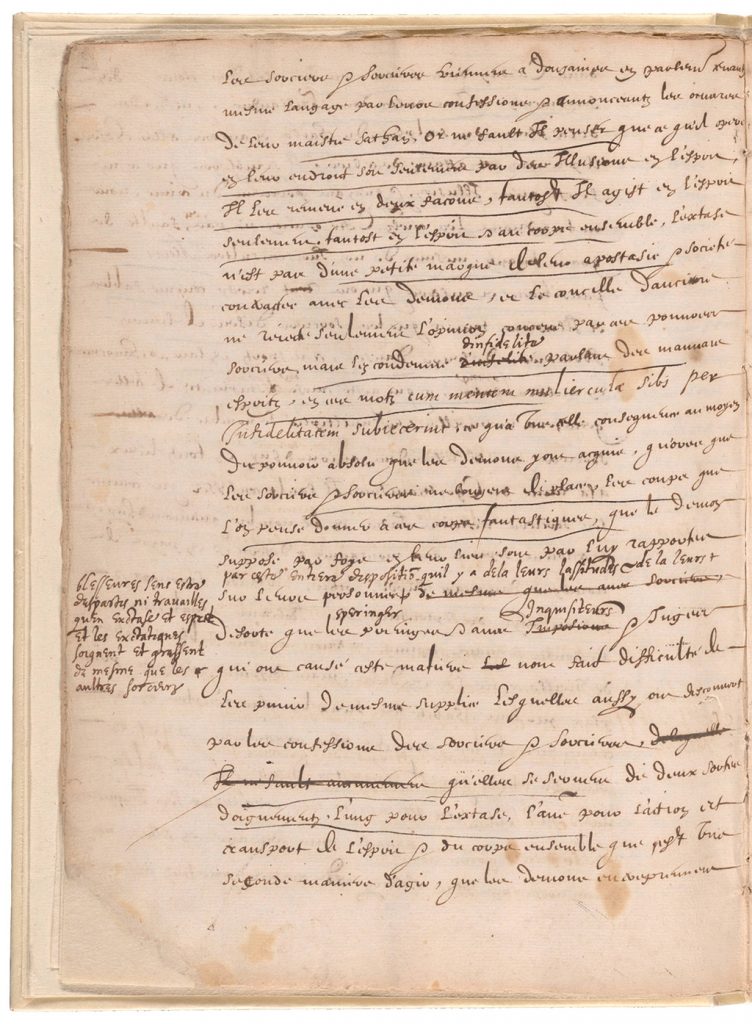

Study of the Ransom Center’s MEM MSS 230 suggests a second possibility, however. The manuscript came into the Center’s possession in 2017. Its title on the cover “Sobre la Licantropía” (On Lycanthropy) would appear to indicate that it spent time in Spain, although its provenance is otherwise unclear. The volume contains two items, numbered 49 and 50 in French, suggesting that it was once part of a much larger collection. The first of these has been titled “Du Loup Garou” (On the Werewolf) and fills almost all of the leaves. The second is a mere two pages but, as we shall see, may be helpful for our discussion of the volume’s authorship.

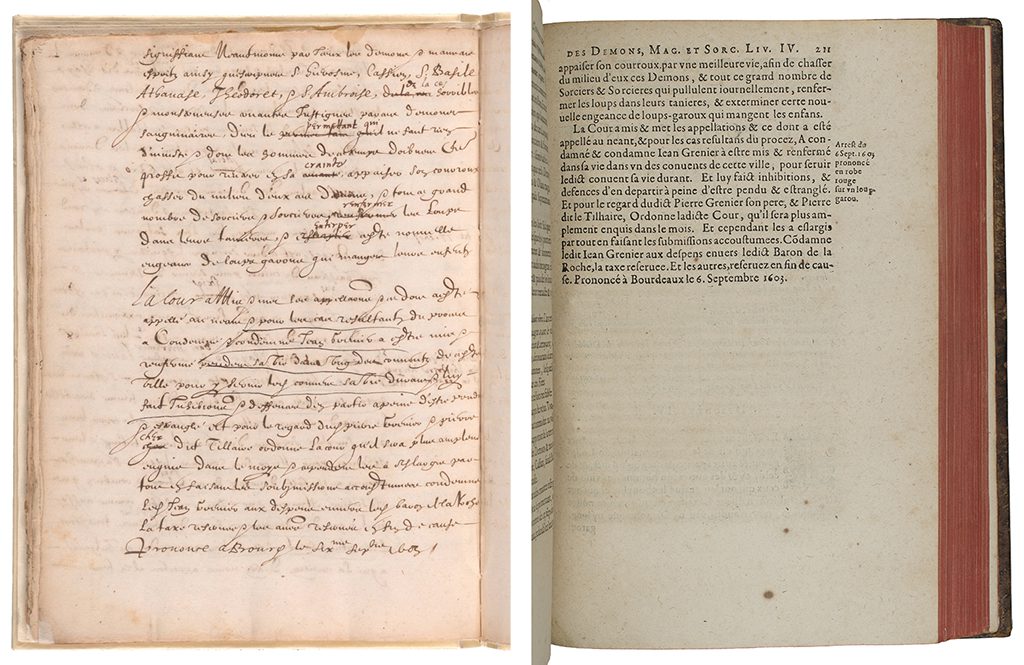

Even a casual glance shows that “Du Loup Garou” is a third version of the same text we examined before, and crucially it starts at the same position as de Lancre’s “judgment” does. Like the version that fell into de Lancre’s hands, it lacks an opening account of the Grenier trial and, yet, appears to be complete. The manuscript thus raises the possibility that de Lancre may have been right—that President Daffis was the author and that the attribution to Filesac in the Mélanges theologiques is mistaken. MEM MSS 230 is certainly written in an earlier hand than MS Français 13346. (Whatever its claims about Filesac’s “own hand” the version included in the Bibliothèque nationale manuscript is by the same late seventeenth-century scribe as the rest of the manuscript.) It seems unlikely, however, that the Ransom Center’s version is the one that came into de Lancre’s possession. MEM MSS 230 did not “pass through an infinity of different hands”—I count only three. In addition to the scribe who wrote the main Grenier text, there is evidence of activity by at least two seventeenth-century readers. One extensively corrected parts of the text. The other hand was much less invasive, likely of a later reader not involved in its original composition. This reader underlined sections of apparent interest and added a few notes in the margins.

The hand that has emended parts of the text offers a potential clue to our authorship mystery. A quick comparison shows that, with one exception, all the corrections were incorporated into the Paris manuscript and de Lancre’s 1612 Tableau. Two solutions thus present themselves. It is possible that the original hand was merely a particularly careless copyist and that the second hand simply checked and corrected shoddy work against another version, such as de Lancre’s Tableau.

Yet the rather early scribal hand and the types of mistakes present both suggest that MEM MSS 230 may well have been considerably more important than that. It is striking that the corrections often pertain to unfamiliar words, often in Latin quotations—the name of an obscure tribe mentioned by Pliny the Elder, for instance, and the name of the little-known Greek historian Palaephatus. Could the original scribe have heard the text (or judgement!) spoken? In that reading, the second hand could have been Daffis himself or, just as plausibly, an educated audience member for whom the document was intended.

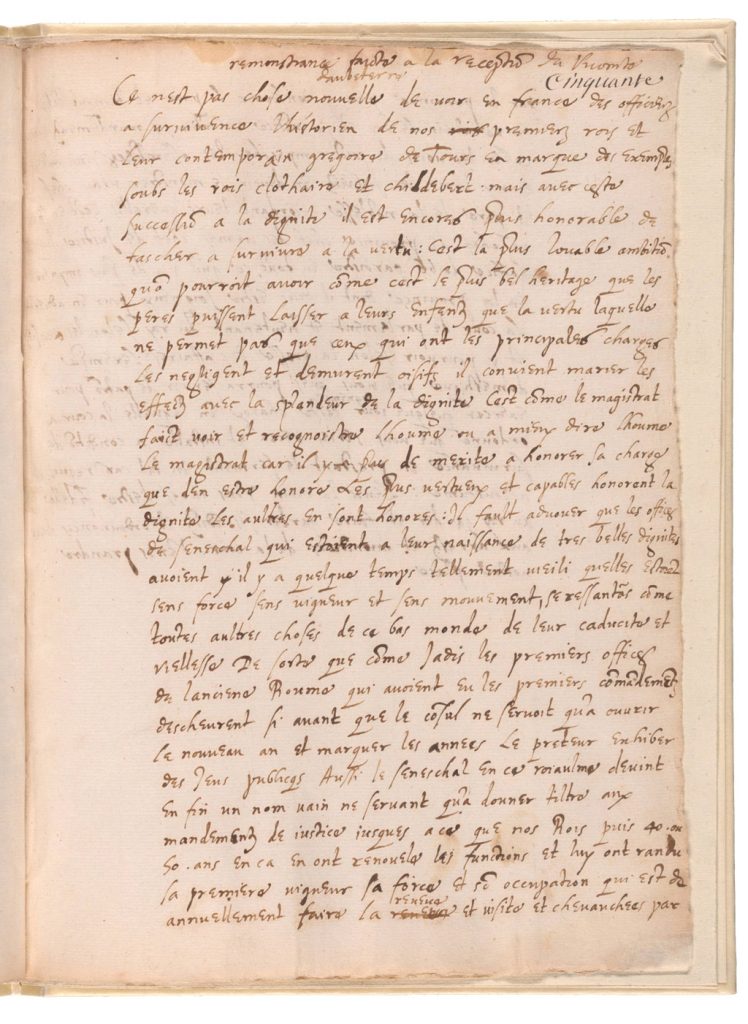

One factor that could support such an interpretation is the second, very short item—number 50—included in the manuscript. Its title, “Remonstrance faicte à la reception du Vicomte d’Aubeterre” (Remonstrance made at the reception of Viscount d’Aubeterre), suggests a similar oral origin and appears to have been written by the same person that emended the Grenier text. Crucially, the individual remonstrated, François d’Esparbès de Lussan, Viscount d’Aubeterre (1571–1628), was a nobleman who held a variety of government positions in the southwest of France during the early seventeenth century, thus placing the manuscript closer to Bordeaux than to Paris and providing further support for an early date.

More careful comparison of the two manuscripts and de Lancre’s Tableau by other (fresher) eyes may bring new hypotheses, but as things stand Filesac’s authorship of this text can no longer be considered a given. Whether MEM MSS 230 is merely another manuscript copy or, more plausibly, closely linked to the text’s composition, De Lancre seems to have been right—the text as preserved in the Ransom Center manuscript may well have been the judgment pronounced in the Grenier case. Daffis’s authorship would explain aspects of this text, notably its ending, although it remains frightfully long and abstract for a sentence. (One wonders how much thirteen-year-old Grenier would have understood.) Other issues also emerge. Daffis’s authorship raises questions about the Paris manuscript—in particular, its first half, which includes details about the trial not found in other sources. Who composed this part, and when, and why, and where? It seems impossible to make all the pieces of the puzzle fit. We may well conclude that these manuscripts have proved as vexing for us today as the issue of lycanthropy was for early modern lawyers and theologians.

Jan Machielsen is Senior Lecturer in Early Modern History at Cardiff University. He is the author of Martin Delrio: Demonology and Scholarship in the Counter-Reformation (2015) and the editor of The Science of Demons: Early Modern Authors Facing Witchcraft and the Devil (2020). He is currently a Humboldt Research Fellow at the TU Dresden, completing a book provisionally entitled Witches, Children, and Refugees: Terror in the Basque Country.