By Haley Price

This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

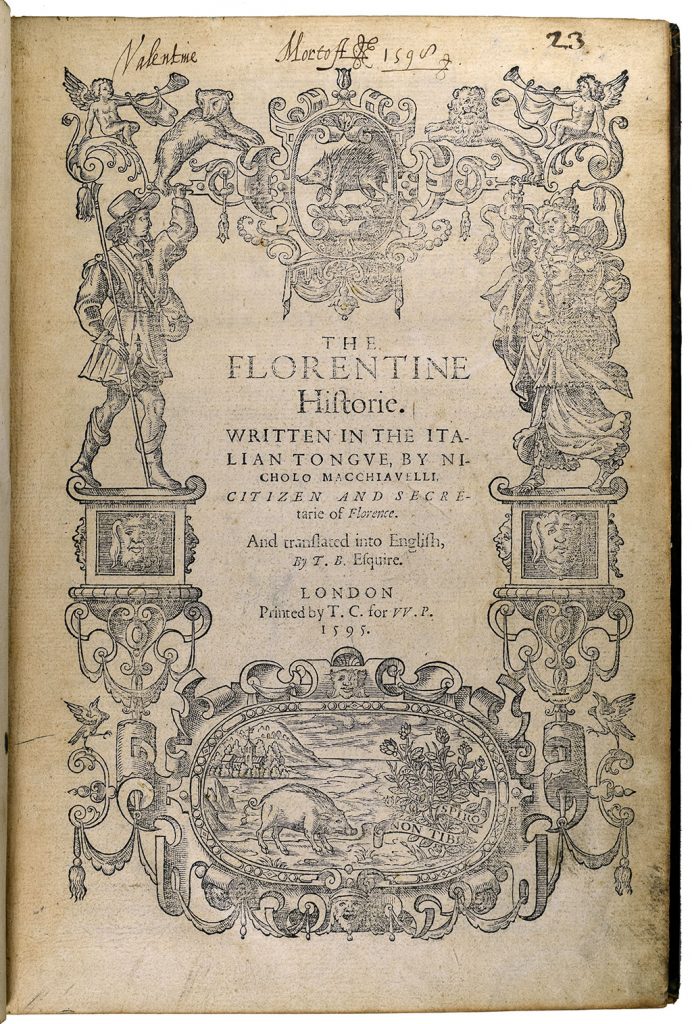

Among the many shelves dedicated to European history in the Harry Ransom Center’s stacks is a first edition of the first English translation of Machiavelli’s Florentine Histories. Thomas Bedingfield undertook the translation from Italian in the later 1580s and saw its publication in London in 1595.

The text is fascinating for many reasons. It was an early introduction to one of Machiavelli’s key works for an English audience. The Center’s copy was acquired by an affluent London merchant, Valentine Mortoft, in 1598, and he surely was one of many readers the book eventually had. My own interest in the text comes, however, from its dedicatory preface. It reveals a fascinating story of patronage sought and apparently never fully realized. This in turn echoes the underlying themes of my undergraduate thesis on the Pazzi Conspiracy of 1478.

Patronage was a vital part of civic life in both Machiavelli’s Florence and Bedingfield’s England. As Paul McLean explains in his classic study, “Florentines sought each other out, face‑to‑face or through letters, to perform a multitude of favors. Such favor seeking was fraught with anxiety, ambiguity, and dissimulation on the part of both petitioners and patrons.”1 But patronage was also fraught with multiple perils.

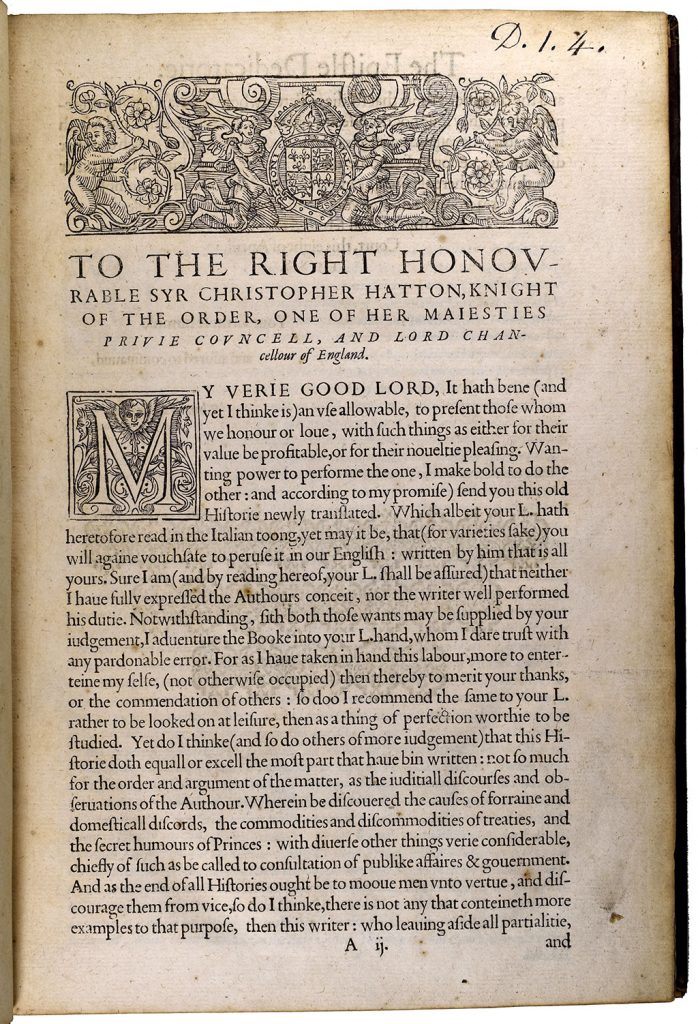

The dedication in the Center’s edition was written by Thomas Bedingfeld on April 8, 1588, fully seven years before the volume was actually published.2 Already well known for his translation skills, Bedingfeld was also already embedded in Queen Elizabeth’s court by the time he entered the orbit of Sir Christopher Hatton in the 1580s. Lord Chancellor of England in 1587, Hatton was one of the central figures in Elizabeth’s government. His influence was far-ranging, which may be why Bedingfeld thought him the perfect choice to dedicate his translation of Florentine Histories to. On the other hand, in another preface to the volume, Bedingfield writes that “The translation . . . was diverse years past desired by an honorable personage, not now living.” This suggests that Hatton may, in fact, have requested the translation in the first place. In the dedication, Bedingfield suggests that an official like Hatton might learn from Machiavelli’s “judicial discourses and observations” on the “causes of foreign and domestic discords, the commodities and discommodities of treaties, and the secret humors of Princes.”3

Bedingfeld’s dedication is a careful mix of humility and praise designed to appeal to Hatton. Although he we do not know all the details, it is hard to see the document as anything less than a bid for patronage; if successful, he would win a powerful ally at court and likely advance his career. Unfortunately for Bedingfeld, Hatton died in 1591, ending his hopes of patronage. We don’t know exactly why it took so long for his Florentine Histories translation to see print, but Hatton’s death may very well have eliminated any sense of urgency for Bedingfield.

The preface reveals a frustrating story of patronage sought but never completely obtained. It may be a historical footnote for most scholars, but it is precisely what interests me. Just as Bedingfeld discovered, patronage is a risky business because it relies entirely on people. They may prove fickle; they may change their minds or they may, as happened with Hatton, die at the wrong time.

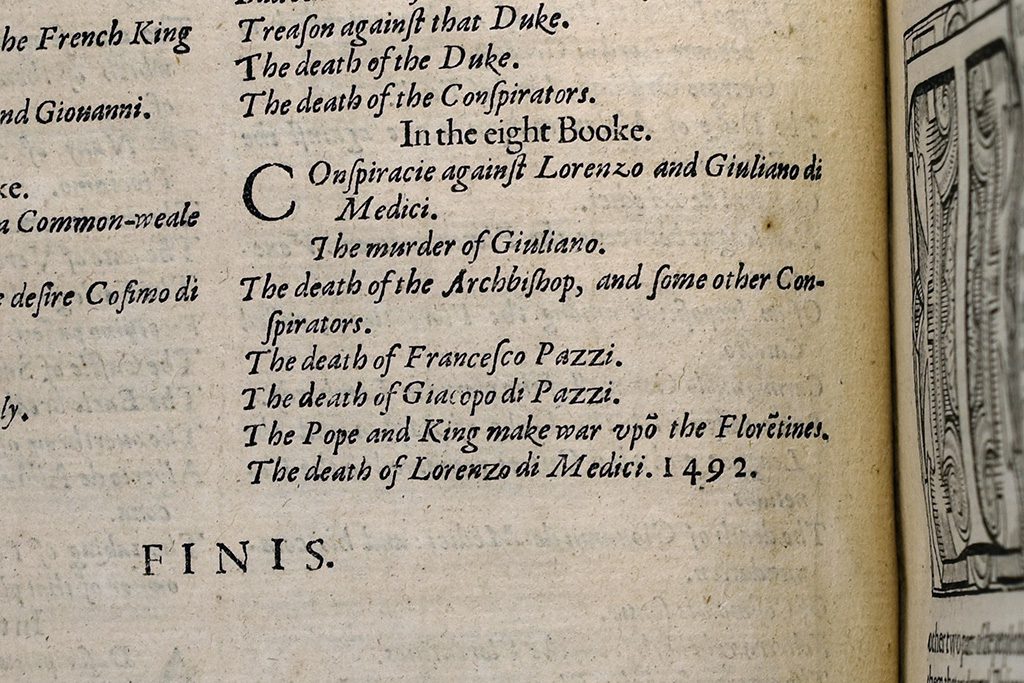

Patronage was a key part of Machiavelli’s world, so of course his Histories reflects its importance. Of particular interest to me is the fact that the last book of Florentine Histories centers on a very famous example of patronage networks falling apart: the Pazzi Conspiracy. To summarize a complex story, a disgruntled group of top statesmen, bankers, and church officials who had all been snubbed by Florence’s most powerful men, Lorenzo and Giuliano de’ Medici, plotted to murder them as revenge and usurp power in Florence.

The Pazzi Conspiracy is the focus of my undergraduate thesis. I use the conspiracy as a case study to illustrate the importance of patronage networks in maintaining Medici power in 1478 Florence. My project shows how a carefully woven network of obligation both secured Lorenzo and Giuliano de’ Medici at the top of the social order, and simultaneously created the very enemies that would plot their murder. Giuliano’s death was a violent consequence of patronage gone wrong, and Lorenzo’s survival very much depended on the clients he was able to keep.

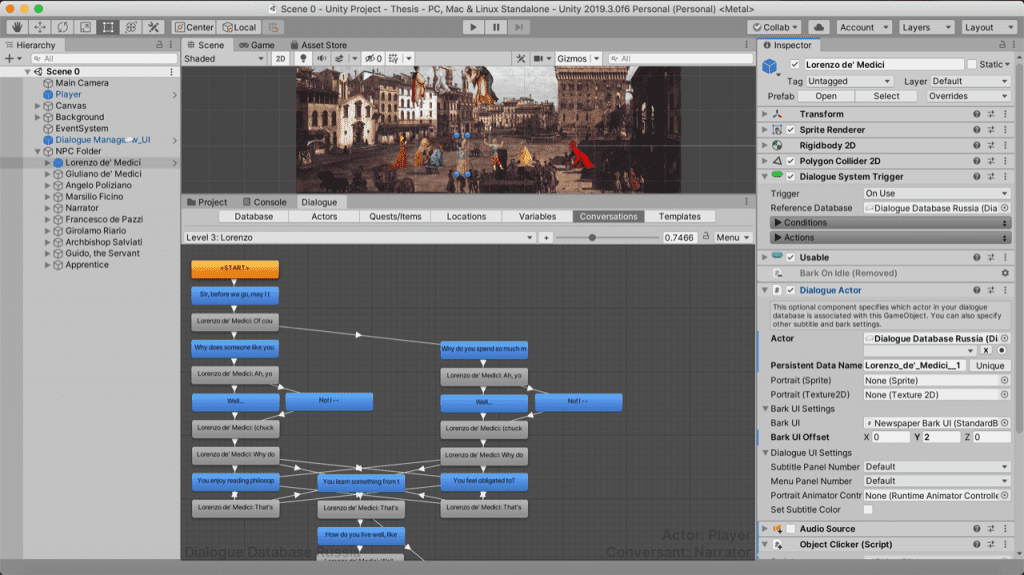

Rather than writing a traditional research paper as my thesis, I decided to develop an interactive video game to show patronage in action and allow my audience to experience the Pazzi Conspiracy in a more immersive way. In my game, students get to participate directly in Medici patronage networks by taking on a role as a servant in the Palazzo Medici at the time of the conspiracy. As the servant discovers the plot to kill Lorenzo and Giuliano over the course of five playable levels, they begin to fear for their own livelihood and that of their masters. If the Medici are killed, the servant will be out of work and likely cast out on the streets, or worse, killed in whatever violent political drama might ensue.

Relying on the wrong person could leave a man helpless, but snubbing the wrong one could get him killed. Lorenzo and Giuliano’s exclusion of powerful men like Francesco de’ Pazzi, Girolamo Riario, and Archbishop Francesco Salviati from their patronage networks provided the catalyst for a murder plot. If the conspirators couldn’t get what they wanted through a relationship of mutual obligation with the Medici, they would just take it by force.

In the end, Lorenzo escaped death and prospered by using patronage networks. Bedingfield had fewer resources but he seems to have navigated the death his would-be patron. Despite the death of Hatton, he was able to find a route to publish the work. After Giuliano’s murder, the Medici family continued to wield power. The way Machiavelli (and many historians) tells it, Lorenzo went on to become the sole hero of the ensuing Pazzi War.4 The war can be spun as a heroic tale with Lorenzo at the center, saving Florence through great bravery, intellect, and self-sacrifice, but mostly with his ability to bring new allies into the folds of his patron-client network. Lorenzo charms his enemy, the King of Naples, into becoming a fierce new ally, and so glues together what’s left of his alliances in Florence and emerges from the war stronger still.5

Patronage was everywhere in this period. It permeates every page of the Florentine Histories, and the early translation preserved in the Ransom Center’s volume offers a perfect example of how fragile such networks could be.

Haley Price is a senior at The University of Texas at Austin majoring in History and Honors Humanities. Her research interests include the nexus between games and history education as well as the Italian Renaissance. She hopes to combine these interests in her senior thesis and go on to pursue further study with a focus on digital history.

1 Paul Douglas McLean, The Art of the Network: Strategic Interaction and Patronage in Renaissance Florence (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 4.

2 Machiavelli, Niccolò. Florentine Histories. Translated by Thomas Bedingfeld. London: T. Creede, 1595. This is the date that appears at the end of the dedicatory letter.

3 Ibid.

4 Machiavelli, Niccolò. “Book VIII.” In History of Florence and of the Affairs of Italy: From the Earliest Times to the Death of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Peter Smith, 1974.

5 Both the Pazzi Conspiracy and the Pazzi War are very complex events. I’ve been studying them for nearly three years and I still have so much to learn. The way I summarized them in this article emphasizes the importance of patronage and the role of Lorenzo as a heroic figure, but as with anything worth studying, it is all so much more complicated than I had space to communicate. For those interested in further reading, the following books are extraordinarily useful:

Hibbert, Christopher. The Rise and Fall of the House of Medici. Penguin Books Limited, 2001.

Martines, Lauro. April Blood: Florence and the Plot against the Medici. Oxford University Press, 2003.