From the Editors: The Climate in Context: Historical Precedents and the Unprecedented conference will take place on April 22-23, 2021. It is free and open to the public. Register to attend here. In preparation for the conference, we are delighted to introduce the work of Dr Bathsheba Demuth. Dr Demuth is Assistant Professor of History and Environment and Society at Brown University and a keynote speaker for the conference.

Sometime in the middle of 2019, I began to see a series of haunting, short articles about nature appear in the mediascape I frequent. The articles were written by a young academic historian with an unforgettable sensitivity and authority about a world I thought I knew — modern Russia and Siberia. I was impressed by the quality of the writing, but I was also impressed by the successful effort of an assistant professor to reach out to readers of a wide range of publications, from big brand names like The New Yorker and The Atlantic, to smallish online magazines with niche audiences like Aeon and Emergence. The author not only described the history and the stakes of environmental calamity in the Far North, but she did so in unusual ways, bringing us closer than I imagined possible to the experiences of the creatures with whom we share our worlds. As someone who has been writing about animism and immersion in nature, I couldn’t wait to read her book, and I wasn’t alone.

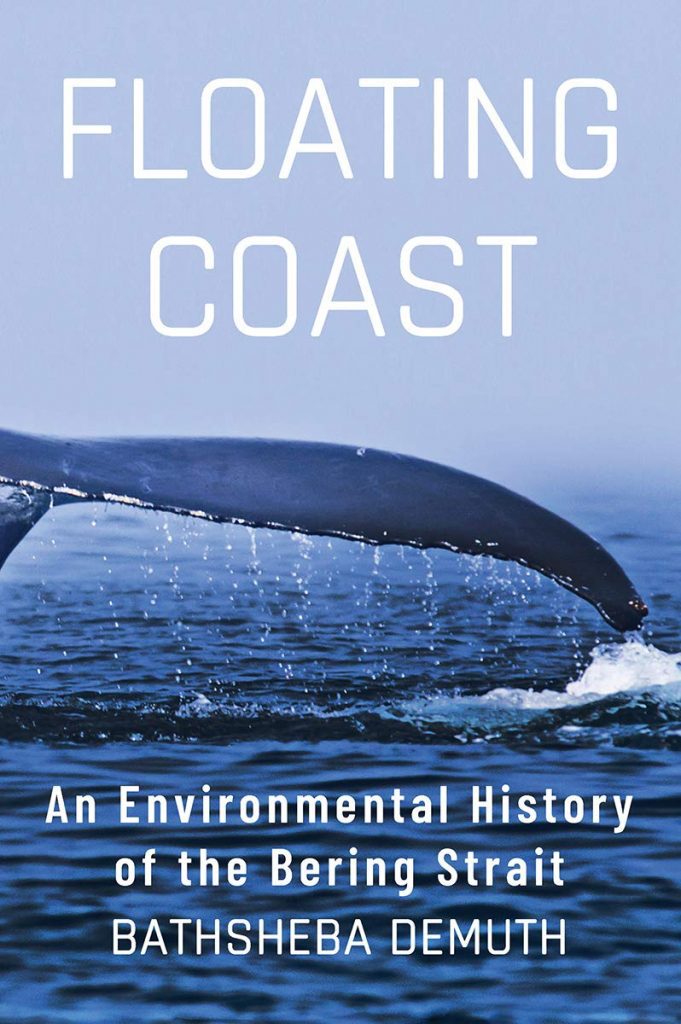

Bathsheba Demuth is Assistant Professor of History and Environment and Society at Brown University. She received her PhD from UC Berkeley in 2016. Her first book, Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait was published by W.W. Norton in 2019 and promptly won a bouquet of prizes, six in all. The book examines the history of the environment on both the U.S. and the Russian/Soviet sides of Beringia and shows the ways that socialism and capitalism had equivalent effects on the region. But the book isn’t about the human impact on land and sea. In Floating Coast, Demuth examines the tangled interactions of the whole ecosystem – animal, vegetable, mineral — over a two-century stretch of time. In so doing, she also compels us to re-think our notions about time itself and the ways that our human experience of past and present merges with the time scales of animals, plants, and place.

It is not easy to write about animals in a way that conveys their experience without seeming false or twee. Demuth does this with remarkably close observation of their movements within their environments, which she joins to description and analysis of the forms of their interdependence that captures plausible motives in their behaviors. Such observations are rooted in Demuth’s own experience. For two years, between high school and college, she lived in the Yukon where she was responsible for a team of sled-dogs. She took care of them and they, literally, took care of her in the extreme weather where they were the experts. Except for that time when they left her in the snow in their rush home to eat.[1]

It is also not easy to write about the environment with anything but despair. However, Demuth also gives us new ways to think about the worlds and bodies we inhabit. This is from an article written last summer, about the fires that have consumed Siberian forests, and raised global temperatures, for years now.

“Playing host to the coronavirus for three months has made me think about normalcy—its shifty character, how it plays with my sense of time—and the drive to pretend that things are at stasis, despite all evidence indicating turmoil. My case of COVID-19 was never acute; I was not on a ventilator or even close, nor do I have the harsher ills of many long-haulers, who report roving pain, memory loss, tachycardia. My experience of the virus has not been an event so much as a shift, erosion rather than earthquake. The most enduring symptom is a corporeal heat wave that shows no more sign of fully lifting than the warmth in northern Eurasia. As the weeks drag on, the hale clarity of my normal self is receding. Perhaps this is just what I am now: weaker, wan, soggy-brained.

As summer tips toward autumn—an autumn in which there will be too little sea ice and too much virus—I do not want to forget the possibilities of my April self, or of Siberia without fire, or of whales by the tens of thousands. The need to build a society that cares for all, that does not let some hide in the safety of distance, has never been more acute. The habits of wealth need reconditioning to account for the real costs of consumption. These are forward-looking projects. My experience of this virus makes me think, however, that we should not forget a longer view, one able to see how the conditions of 2020 are not inevitable. The line of heat that connects my body and Siberia has existed for only a few centuries. It is not inevitable. Thinking past it, as this summer of our many discontents moves into fall, requires a kind of split imagination: to conjure moments of past flourishing, and a future where we might flourish again.”[2]

[1] “The Power of Fear in the Thawing Arctic,” The Atlantic, September 17, 2019.

[2] “The Empty Space Where Normal Once Lived,” The Atlantic, August 28, 2020.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.