By Sarah Porter

Over the past few decades, community organizers and scholars have successfully drawn public attention to mass incarceration in the United States through a variety of mediums including print, film, and digital projects. Yet, the magnitude of the American prison system often encourages researchers and activists to employ quantitative methods. These approaches, while incredibly important and effective, bury the voices and experiences of incarcerated people beneath impersonal statistics and data. However, several recent projects resist these impulses and intentionally place incarcerated people at the center of the story. The American Prison Writing Archive (APWA) offers one example. The APWA grew from an effort to collect and publish essays written by incarcerated Americans. Doran Larson, a Professor of Literature and Creative Writing at Hamilton College, and his collaborators issued a call for submissions and compiled over seventy of these essays in their 2014 collection, Fourth City.[1] After the 2012 submission deadline, essays continued pouring in, signaling the need for an ongoing effort to collect and archive these stories.

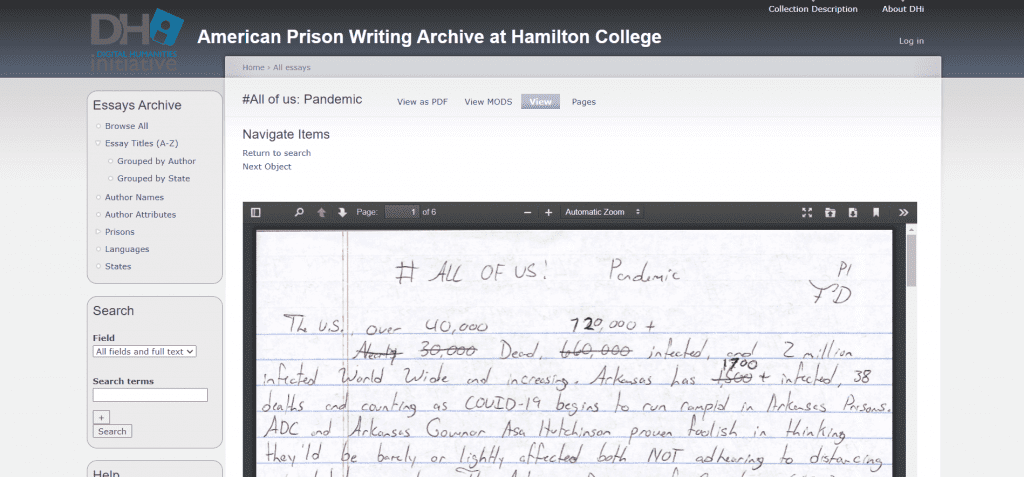

According to Larson, the APWA strives to create a “living, growing, and inclusive” witness literature by providing a platform for “those best positioned to articulate and critique the deeply personal and collective suffering exacted by the current legal order.”[2] In its present format, the APWA is an open-source, online database that contains more than 3,000 non-fiction writings submitted by incarcerated people, prison workers, and prison volunteers. The project is based at Hamilton College and has received funding from the school’s Digital Humanities Initiative and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Essays are continuously added to the collection, and many address recent issues including the devastating spread of COVID-19 through prisons and jails. The APWA solicits essays through prison publications and Prison Legal News, a monthly magazine. Writers may request a permissions-questionnaire (PQ), which provides basic guidelines for submissions and gathers voluntary demographic data. Submissions are then read, scanned, and uploaded to the database.

In contrast to Fourth City, in which editors carefully selected and curated essays, the APWA offers a much more interactive experience. Visitors to the site can browse essays or use the search feature to narrow results by state, prison, language, and authors’ self-identified characteristics, including ethnicity, gender, and age.[3] Staff and volunteers have also transcribed most of the essays, and their contents are fully searchable. Unfortunately, it is more difficult to find entries from a specific date or year, and not all of the essays contain detailed metadata. The APWA also invites visitors to participate in the project by transcribing handwritten essays or completing subject tagging. This process is relatively simple. After registering through the website, volunteers receive brief instructions explaining how to access the essays and the guidelines for transcription and subject tagging. By participating in this process, volunteers are able to act as secondary witnesses, making the words of incarcerated Americans available to a broader public.

In addition to transcribing essays, readers and visitors to the site may also further the project goals by using the collection contents in innovative ways to direct attention to issues that incarcerated people face. Essays hosted on the site address many pressing concerns including healthcare, prison overcrowding, and voting rights. These valuable perspectives can influence public discourse. Consider, for instance, an essay from 2020 submitted by Charles Brownell. Writing from an Arkansas prison, Brownell describes his experience witnessing the spread of COVID-19. According to Brownell, the Arkansas Department of Corrections (ADC) often relies on open barracks, a form of prison construction that is less expensive than conventional cell blocks but ineffective in stopping or slowing the spread of disease.[4] In fact, another ADC unit experienced a surge in cases in April 2020 among those housed in the open barracks, with 44 of 47 inmates contracting the virus.[5] While the ADC did implement some precautions, including distributing cloth masks manufactured by inmates, Brownell suggests that these measure were insufficient. He revealed that “each inmate has a single mask and no way to sanitize [it].”[6] Accounts like this one provide powerful testimony and can be used in a number of ways. Policymakers and advocates, for example, should rely on writers’ insights to develop policy proposals and guide community organizing efforts. Teachers might use essays as primary sources in the classroom. Researchers studying incarceration or related topics can also incorporate these writings into their work.

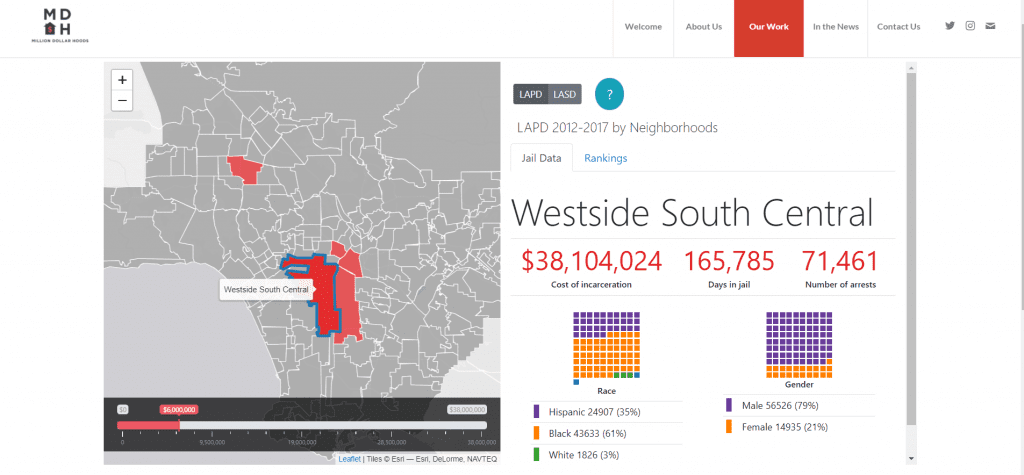

A variety of digital and analog projects have joined the APWA in confronting mass incarceration in creative ways. Other digital archives, such as the Washington Prison History Project, offer more historical perspectives. This collection, which was developed by historian Dan Berger, includes prison publications from the 1970s and 1980s, such as The Abolitionist and the Anarchist Black Dragon. The collection also includes a selection of oral histories, interviews, and the personal papers of Ed Mead, a prison activist and former member of the Seattle-based George Jackson Brigade. Another example is Million Dollar Hoods (MDH), a digital project developed by UCLA professors Kelly Lytle Hernandez and Danielle Dupuy. According to the project website, MDH “maps and documents the human and fiscal costs of mass incarceration in Los Angeles and beyond.”[7] The team collects and analyzes data to produce interactive digital maps that reveal how much money Los Angeles spends on incarceration in specific neighborhoods. In addition to data mapping, MDH works with community-based groups to produce short research reports, conduct oral histories, and compile historical records into an archive.

Viewed as a whole, the APWA and subsequent projects represent important efforts to add the voices of incarcerated Americans into conversations surrounding prison reform and abolition. They also provide models of collaboration for future projects. As new technology alters the landscape of prison organizing and research, it is essential to create spaces that remain accessible to those at the forefront of these struggles.

Sarah Porter is a second year PhD student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. She studies twentieth century social movements and mass incarceration in the United States. Her current research centers on the legal and political challenges that activists mounted against the Texas Prison System between 1960 and 1980. At UT, Sarah serves as a Graduate Research Assistant to Dr. Ashley Farmer and works on Dr. Monica Martinez’s Mapping Violence research team. Sarah also volunteers with the Inside Books Project, an Austin-based organization that sends free books and educational materials to people inside Texas prisons.

[1] Doran Larson, ed., Fourth City: Essays from the Prison in America (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2014).

[2] Doran Larson, “Witness in the Era of Mass Incarceration,” American Quarterly 70, no. 3 (2018): 599.

[3] The vast majority of the essays are in English, but the APWA currently contains 17 submissions in Spanish. A few other searchable author attributes include age at conviction, sexual orientation, religion, birth year, and veteran status.

[4] Charles A. Brownell, “#ALLOFUS: Pandemic,” 2020, American Prison Writing Archive, https://apw.dhinitiative.org/islandora/object/apw%3A12360115?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=cabee266feed7040147d&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=0.

[5] John Moritz, “44 of 47 inmates infected in Cummins prison barracks,” Arkansas Democrat Gazette, April 14, 2020, https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2020/apr/14/44-of-47-inmates-infected-in-cummins-pr/.

[6] Brownell, “#ALLOFUS: Pandemic,” 3.

[7] “About Us,” Million Dollar Hoods, accessed April 22, 2021, https://milliondollarhoods.pre.ss.ucla.edu/about-us/.