From the editors: In 2021, Not Even Past launched a new collaboration with LLILAS Benson. Journey into the Archive: History from the Benson Latin American Collection celebrates the Benson’s centennial and highlights the center’s world-class holdings.

In Spanish, the word relación encompasses both to narrate (relatar) and to connect (relacionar). The Relaciones genre, prevalent from the fifteenth to the sixteenth centuries, incorporates this dual aspect. They consisted of short reports to the imperial government about a person, community, or town. These accounts help show the nature of the relationship between those narrating (communities), those that were the object of narration (towns), and those receiving the information (the empire). Emerging from the relación genre, the Relaciones Geográficas (of the New World) and the Relaciones Topográficas (of the Castille) were comprised of maps and texts describing hundreds of communities throughout the late 16th-century Spanish empire. Scholars who have delved into these documents have tended to follow the structure of archival memory that distinguished the Relaciones Topográficas from Geográficas. Moreover, studies on the Geográficas have primarily focused on the texts produced for the townships of New Spain (Mexico). Scholars are right to be intrigued by the Relaciones maps of New Spain. Consider Map 1 depicting Cempoala through Nahuatl logograms and Spanish texts.

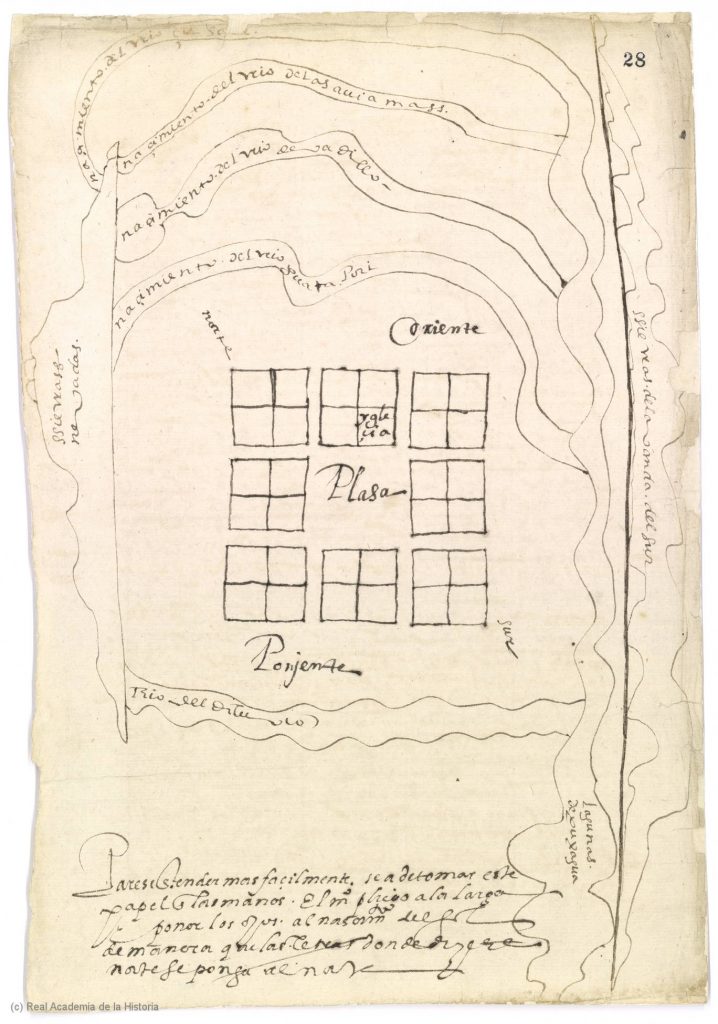

My life’s story has come to be entwined with the history of the Relaciones. My intellectual place of origin, Bogotá, Colombia, facilitated my first encounter with them. My continued engagement with these sources from Latin American classrooms and special collections to Spanish archives has culminated in my current dissertation project at the University of Texas at Austin – the principal observatory and repository of these documents in the Americas.[1] My life and research paths have allowed me to explore this neglected historical terrain. I argue that by drawing together the Relaciones Geográficas and Topográficas as a genre of documents, we can better envision how people from diverse ethnic compositions on both sides of the Atlantic produced a massive number of descriptions of local nature and societies around the same period. This perspective may allow us to see and understand the complex knowledge networks of Atlantic towns that the Spanish Crown wove together. Consider, for instance, how the Relaciones go beyond the famous Mexican indigenous charts as revealed by Map 2, the Relación of Valledupar, a township located in what is now Colombia.

My first encounter with the Relaciones was not via the vibrant native maps of New Spain as experienced by many scholars from the global north, but through the Relación de Valledupar (Map 2). During an undergraduate course on Colombian geography, I was assigned to analyze and contextualize this document with the earliest known map of this tiny Caribbean town. The map shows an urban design based on a square grid, principal rivers, mountains, and no indigenous glyphs. At first glance, I was surprised by how close this 1580s map was to our modern understandings of space and knowledge-making. Its empiricism and “cartesian” portrayal of the environment took place years before Descartes wrote his works. Through this piece, we can see how a peripheral village conceived of its environment, demography, and connections to the empire and did so by answering a survey, as in modern governmental censuses. I fell in love with this topic and drafted my honors thesis about the Relaciones of Santa Marta.[2]

My honors thesis work quickly brought me to the realization that the Valledupar Relación was just one tiny piece of a puzzle formed of hundreds of similar manuscripts and maps composed between 1575 and 1590 under the rule of Philip II. In the Universidad de Los Andes, my alma mater, I found not only marvelous transcriptions of the many Relaciones from Peru and New Granada, but also the excellent book by Barbara Mundy about the Relaciones of New Spain.[3] I began to realize that the Relaciones could help us re-think the connections that may have existed among various Spanish-American communities in this knowledge-crafting effort. My place of origin mattered for this argument because I began to identify with past and present Spanish-Americans who have engaged in processes of interpreting our historical realities. By doing so, we have produced and continue to produce knowledge about ourselves, not only through (or following on from) European and U.S.-American academic views.

Thanks to Los Andes’ library’s collections, I also learned that the Relaciones are now dispersed worldwide, and it has been challenging to bring them together. Roughly speaking, the current location of these documents depends on the place they described. I learned that the Relaciones Geográficas encompass over 250 reports from New Spain, New Granada, Venezuela, Peru, Ecuador, Central America, the Caribbean, and that the Relaciones Topográficas covered over 700 municipalities in the Kingdom of Castille. El Escorial hosts more than seven hundred Relaciones Topográficas de España that depicted Castilian towns. The Real Academia de la Historia keeps 19th-century copies of these Castilian reports and many of the Relaciones of New Granada, Venezuela, and New Spain, some of them with their own maps. In addition, the University of Glasgow hosts the Relación Geográficas de Tlaxcala. At UT Austin, the Benson Latin American Collection shelters forty-three Relaciones’ manuscripts and twenty-six maps (also known as pinturas) from Mexico and Guatemala. Finally, the Archivo General de Indias possesses at least a hundred Relaciones’ texts and more than a dozen maps from the whole New World.

In 2017, the Colombian government awarded me a research grant to travel to Spanish archives and delve more deeply into the history of the Relaciones. In the Real Academia de la Historia, I became curious about the similarities between the Relaciones Geograficas and Topograficas, usually considered entirely separate efforts. Scholars and archivists after the sixteenth century assigned the labels “Geográficas” and “Topográficas” to distinguish New World descriptions of municipalities from those of the Old World. And yet, I came to see how both corpora were essentially chorographical—i.e., town descriptions and were remarkably similar conceptually. Consider the titles to the questionnaires reproduced in figures 1 and 2. Notice how similar they are: “Instrucción y Memoria de las Relaciones que se han de hacer para descripción de las Indias […] para el buen gobierno y ennoblecimiento de ellas” (for the Geográficas),[4] and “Instrucción y Memoria de las Relaciones que se han de hacer […] para la descripción y historia de los pueblos de España […] para honra y ennoblecimiento de estos reinos” (for the Topográficas).[5] The Royal Cosmographers López de Velasco and Vásquez de Salazar designed parallel surveys in the same decade to describe both the Indies and Castille (respectively) at the municipal level for enhancing their governmentality. Despite the similar purposes and timing, they differed in some questions about landscape and customs’ description. Additionally, the Topográficas were more numerous and briefer, while the Geográficas were usually more prolonged, and many included maps.

The project that led me to UT Austin has been to reconnect and recontextualize the Relaciones Geográficas and Topográficas as ambitious bottom-up knowledge endeavors about nature and human communities during the Early Modern period. However, since they did not produce tangible results like an encyclopedic compendium of Spanish municipal geography, some scholars still see them as either as curiosities or even as failed efforts. Shifting attention away from the Relaciones questionnaires, their two cosmopolitan white male designers, and subsequent uses of the reports may open a path towards an alternate understanding of why these documents are valuable. I argue that we need to understand how these documents reveal the collective efforts of thousands of ordinary people in these townships. At the end of the day, the real creators of the Relaciones were their communities themselves.

Each municipality responded to the questionnaire and sent it back to the cosmographers. But the process of generating responses to the questionnaires was complex. Every town council summoned courtroom meetings in which local sages stated their answers and drew maps. They discussed toponymies, climate, fauna, flora, minerals, topography, customs, traditions, and urban layouts. Answering questionnaires was not rare in the Spanish legal culture of interrogatories. Nevertheless, employing these methods to craft empirical knowledge about nature and societies was not common. Before a scribe notarized it, these officials and local sages signed and approved their responses through ritualized agreements.

The consensus these documents show elides frequent factional struggles occurring in these townships, highlighting instead the minimal agreements formed amongst powerful elites. Eliding political competitors through these representations nevertheless offered political gains. The Relaciones often excluded key political actors’ direct participation and hid local conflicts that would be visible to the Crown via other mechanisms, especially a massive number of litigation cases. Those who successfully answered these questionnaires then implicitly represented themselves as reliable producers of knowledge valuable to the Crown. They also showed themselves powerful enough to tap into local knowledge about places produced by people of diverse ethnic backgrounds, for instance, to know the meaning of native toponymies. In this sense, the Relaciones can be considered selective narrations that may distort the complexity of town life, yet they also show how different communities participated in producing knowledge elicited by Crown questionnaires. These complex dimensions are what make the Relaciones valuable as historical documents.

The Relaciones enable comparisons between distant towns thanks to the questionnaire’s structure. They also offer historical snapshots for hundreds of tiny municipalities in regions lacking documentation, such as the Caribbean basin. Many show valuable information in the indigenous lexicon. We can learn much about early modern ways of knowing nature and humans from reading the Relaciones on their own terms and interrelatedly. The knowledge created was similar to what we now label “modern science”: empirical, organized, participative, and consensual. Currently, my research efforts point towards thinking about a systematic way to show, analyze, and compare these sources through digital and cartographical tools.

To conclude this personal and analytical trip through the Relaciones, I would like to invite the readers of Not Even Past to join the discussion of these sources that will take place next February 2022 in the Lozano Long Conference in honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection: “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives.” In that event, we will have a panel called “Modern Institutional Networks Visualizing Early Modern Archives: The Case of the Relaciones Geográficas y Topográficas,” which aims to explore the archival and digital possibilities of cooperating in facilitating the access and analysis of these documents. We have invited digital humanities practitioners and archivists who have worked with or have custody over these manuscripts and maps in different archives and collections worldwide. We encourage anyone who is intrigued by these sources to attend this event that will take place virtually.

Rafael Nieto-Bello is a second-year Ph.D. student in the Department of History at UT Austin. He obtained a double B.A. in History and Political Science and a double minor in Philosophy and German Language in the Universidad de Los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia, 2018). In 2021, he was awarded the Fellowship on “Race and Caste” from the Institute of Historical Studies (IHS) for preparing a grant proposal. Additionally, he obtained the Lozano Long Centennial Fellowship from LLILAS Benson for the coordination of the 2022 Lozano Long Conference “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives.” His research is a history of knowledge from the 16th-century Spanish municipalities. He explores how town communities from diverse ethnic backgrounds described and claimed to know their populations and environments through corporate efforts placed on the local councils.

DIGITAL HUMANITIES AND ARCHIVAL CATALOGUES

LLILAS Benson Relaciones Geográficas Collection:

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=1fcabf740a844d9d80d5bf0248416f47

New World Nature: https://nwn.dhinitiative.org/

Unlocking the Colonial Archives: https://unlockingarchives.com/

KEY BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

Campos, Francisco Javier. “Las Relaciones Topográficas de Felipe II: Índices, Fuentes y Bibliografía (Separata).” Anuario Jurídico y Económico Escurialense2 36 (2003).

Cline, Howard F. A General Survey: The Relaciones Geográficas of the Spanish Indies, 1577-1586. A General Survey: The Relaciones Geográficas of the Spanish Indies, 1577-1586. HMAI Working Papers ; 39. Washington, n.d.

Jimenez de la Espada, Marcos. Relaciones Geográficas de Indias. Peru. Madrid, 1897.

Konyushikhina, Nadezhda. “The Past in Everyday Perception of the Spaniards of the 16th Century (Based on ‘Relaciones Topográficas de Felipe II’).” Istoriya 9, no. 10 (74) (2018). https://doi.org/10.18254/S0002503-2-1.

López Gómez, Julia, and Antonio López Gómez. “Cien Años de Estudios de Las ‘Relaciones Topográficas de Felipe II’ Después de Caballero.” Arbor, no. 538 (October 1, 1990): 33-.

Mundy, Barbara E. The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Nichols, Madaline W. “An Old Questionnaire for Modern Use: A Commentary on ‘Relaciones Geográficas de Indias.’” Agricultural History, no. 4 (October 1, 1944): 156-.

Nieto-Bello, Rafael David. “Descripciones Para El Buen Gobierno y Provecho de La Tierra, Vecinos e Indios Samarios: Conocer Las Provincias de Santa Marta a Través de Las Relaciones Geográficas de Indias (1577-1582).” Universidad de Los Andes, 2017. https://ezproxy.uniandes.edu.co:8443/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat07441a&AN=cpu.795129&lang=es&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Tovar Pinzón, Hermes. Relaciones y Visitas a Los Andes / Hermes Tovar Pinzón. Relaciones y Visitas a Los Andes. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, 2010.

Vallina Rodríguez, Alejandro, and Nadezhda Konyushikhina. “Los Interrogatorios de Los Catastros Españoles de La Edad Moderna: Fuentes Geohistóricas Para Conocer Los Paisajes y Las Sociedades.” Catastro, no. 89 (2017): 39–62.

[1] Among pioneer works produced at UT Austin, we can highlight these ones: Nichols, “An Old Questionnaire for Modern Use: A Commentary on ‘Relaciones Geográficas de Indias’”; Cline, A Gen. Surv. Relac. Geográficas Spanish Indies, 1577-1586.

[2] Nieto-Bello, “Descripciones Para El Buen Gobierno y Provecho de La Tierra, Vecinos e Indios Samarios: Conocer Las Provincias de Santa Marta a Través de Las Relaciones Geográficas de Indias (1577-1582).”

[3] Jimenez de la Espada, Relaciones Geográficas de Indias. Peru.; Tovar Pinzón, Relaciones y Visitas a Los Andes / Hermes Tovar Pinzón.; Mundy, The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas.

[4] “Instruction and Memory of the Relaciones to describe the Indies’ provinces […] for their good government and ennoblement.”

[5] “Instruction and Memory of the Relaciones for the description and history of the towns of Spain for the honor and ennoblement of these kingdoms.”

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.