In 1914, the United States was an emerging world power. Many of its citizens looked forward to a future defined by more extensive American involvement in global affairs. However, their growing optimism also masked profound disagreements about the kind of role Americans should play on the world stage. Some wanted their country to challenge the political, economic, and military dominance of its European and Japanese rivals. Others hoped that American leaders would ensure perpetual peace by extending the scope of international law, liberal democracy, or corporate capitalism. Rival policy agendas vied for attention in the halls of power and the popular press, sparking heated public debates that touched on virtually every aspect of American foreign relations. The debates themselves, which highlight the broad spectrum of possibilities open to American foreign policymakers at the dawn of the “American Century,” are endlessly fascinating. But because of their variety and complexity, they are also quite difficult to study.

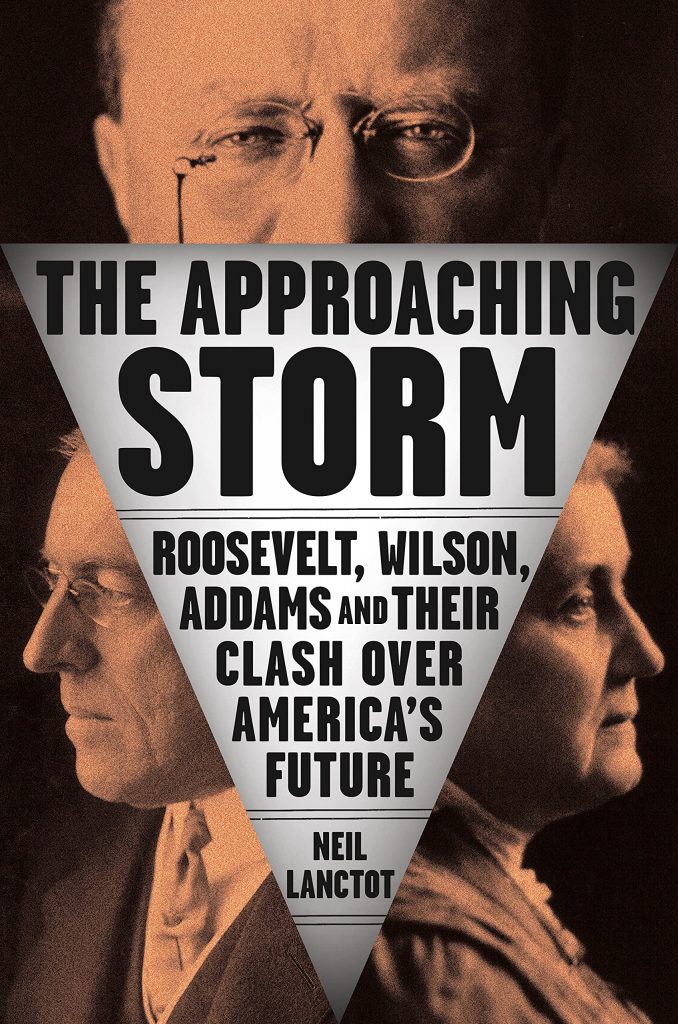

The Approaching Storm, a forthcoming book by popular historian Neil Lanctot, attempts to solve this problem by focusing exclusively on the contentious debate over the possibility of American intervention in the First World War. The outbreak of war in Europe at the end of July 1914 dramatically intensified the rivalry between hawks and pacifists in the United States, bringing their worldviews—and the differences between them—into much sharper focus. The ensuing “clash over America’s future” pitted some of the country’s most influential politicians and thought leaders against one another. Three of them occupy center stage in Lanctot’s book: President Woodrow Wilson; his archrival Theodore Roosevelt, who became the leading advocate of military preparedness and war with Germany; and Jane Addams, a world-renowned social reformer and pacifist. The Approaching Storm colorfully describes their involvement in the intervention debate. More ambitiously, it also tries to locate the source of their profound disagreements about the future of American foreign policy. Lanctot contends that his protagonists’ “starkly different” responses to the First World War reflected their “unique visions of what America could and should be” (21).

Although The Approaching Storm is based on extensive archival research, it is primarily intended for popular consumption and eschews extensive engagement with relevant historical scholarship. Nevertheless, professional historians and policy experts will find plenty to admire in Lanctot’s accessible and engaging book. The author is at his best when he writes about Addams, whose pacifism seems a logical extension of her commitment to social justice and her faith in the meliorative power of expertise. His portraits of Roosevelt and Wilson are less analytically rich, but they’re still incisive. The Approaching Storm hints at a relationship between Roosevelt’s obsession with manliness, his assertive approach to domestic politics, and his eagerness for war. It also calls attention to Wilson’s “Machiavellian” political savvy, subtly challenging outdated realist caricatures, which cast the President as a hapless idealist.

Source: Library of Congress

Lanctot’s boldest and most provocative intervention may be his decision to reframe the wartime intervention debate as a three-cornered contest. Much has been written about the rivalry between Roosevelt and the more cautious Wilson, who initially supported American neutrality. Yet in The Approaching Storm, it is not Wilson but Addams who draws the sharpest contrast with the hawkish “TR.” Long before Wilson began touting his plans for a League of Nations, Addams envisioned and tried to execute an ambitious, dynamic peacekeeping strategy. Her ultimate goal was to place the United States at the head of a conference of neutral powers capable of ending the war in Europe by diplomatic rather than military means. Lanctot takes this plan very seriously, praising Addams’ pragmatism and pointing out how close she came to winning allies in high places.

Addams, of course, did not emerge victorious from the intervention debate. Instead, in April 1917, Congress—to Roosevelt’s delight and at Wilson’s request—declared a “war to end all wars” against Germany. It was a fateful decision, signaling that the United States was now willing to use armed force against perceived threats to world order. But as The Approaching Storm makes clear, the choice for war was far from preordained. By presenting Addams’ pacifism as a viable policy agenda, Lanctot’s book reminds us that the seemingly inevitable transformation of the United States into a great military power was not, in fact, inevitable at all. Between 1914 and 1917, American leaders could have steered their country down a very different path, committing themselves to forging world peace without fighting Wilson’s “war to end all wars.” Today, as shifts in the global balance of power make American military supremacy increasingly difficult to maintain, that’s something worth thinking about.

John Gleb is an America in the World Consortium Pre-Doctoral Fellow at the Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs in Washington, D. C. He is also a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin, where he earned his MA in May 2020. John received his BA at the University of California, Berkeley, from which he graduated with High Honors and Highest Distinction in 2017. At UT, he is a Graduate Student Fellow at the Clements Center for National Security and has appeared as a guest on The Slavic Connexion, a podcast affiliated with the Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies. He is also fluent in French. John’s research focuses on the rise of the American national security state and on the relationship between foreign and domestic politics in the United States. He is especially interested in the concept of political consensus, a yearning for which has decisively shaped the worldview and activities of American foreign policymakers since the turn of the twentieth century. John’s dissertation will examine attempts to forge a foreign policy consensus both inside and outside the halls of government between 1900 and 1950. Thanks to those early consensus-building campaigns, the national security state that emerged during the Cold War would consist of more than just a cluster of institutions: as John will show, it also encompassed (and continues to encompass) a system of shared values and ideas from which those institutions had to draw power in order to compensate for their formal weakness.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.