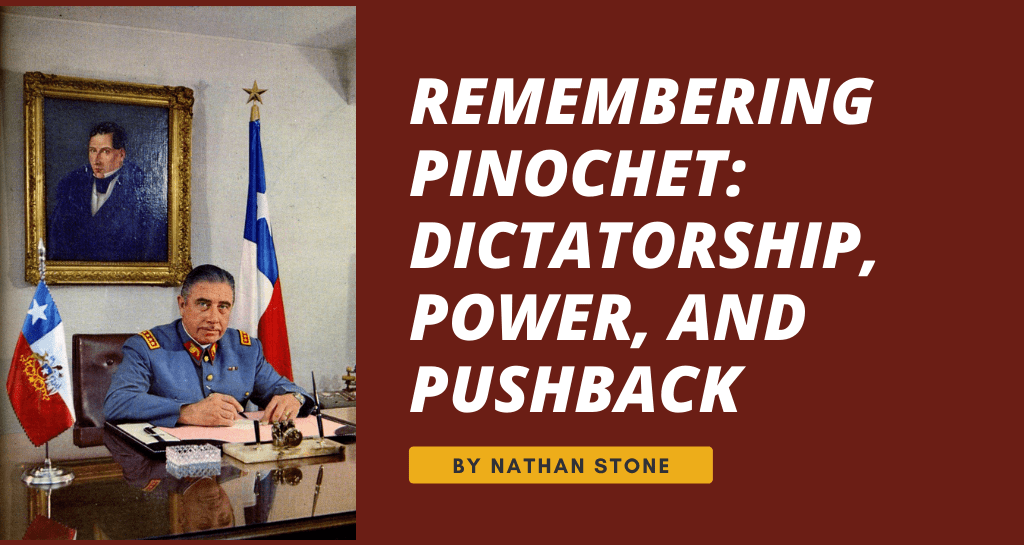

For the plebiscite of ‘88, Chile had its first political campaign in fifteen years. La Campaña del NO tried to make it fun. We all had many dark tales to tell, and maybe a moral obligation to tell them, but sad stories don’t get votes. Moreover, a very fine line, invisible to carabineros, divided protesting and campaigning. Opposition supporters had to resort to clever strategies. We would drive around with their windshield wipers on, on a dry day. Like saying “no” by moving your index finger from left to right. The cops couldn’t exactly arrest you for using your windshield wiper.

If you had to use the horn, the cadence was ta-tá, ta-tááá. It sounded like the slogan, y va caer—literally, it’s about to fall—the wishful refrain that had been around since the ‘70’s, calling for the military government to implode. Our efforts fell short of actual revolution, but we had to start somewhere.

I drove an old, white Renoleta at the time. That was the local nickname for the Renault 4, the archetypal poor man’s car. Pragmatic French engineers had stripped it down to the basics. Mine only had one wiper, because the other had gotten stolen. Even so, me and my car, we did what we could to topple the tyrant.

Most people with cars were voting, SÍ. That meant another ten years of Augusto Pinochet; so, you had to be careful with the wipers in Vitacura. Communist car like mine, it could be the plumber or the electrician, but it couldn’t stay parked on the street overnight, not in the barrio alto. If your wiper came on, the cops might not touch you, but you could get hit by a reactionary rock from the teenaged children of Chile’s blue bloods. Santiago’s pseudo-aristocrats called themselves the GCU, Gente Como Uno, “folks like us.” They didn’t like Tío Augusto, not really. They found him bull-headed and unrefined. But his ruthless violence kept them in power.

The political conglomerate campaigning for the negative option called itself, La Concertación por la Democracia, or just, la Concertación, for short. With nothing else to do, the parties, both radical and moderate, had spent the entire time since 1973 subdividing into smaller and smaller factions and arguing about ideological minutia. By 1986, the time had come. We had to get over it. Even die-hard capitalists wanted a change. Monthly protests had made neoliberalism at gunpoint bad for business, and fatal for tourism.

The coalition sprouted fully formed out of the brain of Raúl Troncoso. He had pulled strings behind the scenes since the ‘60s. In the ‘80s, he took some pretty big risks to get that bulky rocket off the launching pad, including personally smuggling briefcases full of cash from Europe for the purpose of toppling the Pinochet regime without firing a shot. And he pulled it off.

Troncoso had served as chief of staff for President Eduardo Frei in ’64. He became an advisor to Eduardo Frei (the younger) when he became President in ’94. On October 16, 1998, Pinochet got arrested in London, where he had gone with his wife for a minor surgical intervention and major shopping expedition. He had been indicted in Spain. Ironically, as Minister of the Interior for the younger Frei, it became Troncoso’s job to defend Pinochet from extradition to Spain when Judge Baltazar Garzón wanted to put him on trial for torture, murder and conspiracy.

Why didn’t they just ignore it and let him go to jail in Spain? Love thy enemies? Better to love that one from as far away as possible. The official story affirmed that Chilean courts should have jurisdiction and that the former dictator could only be properly tried at home. Which was silly, because obviously, that wasn’t happening. There was a strategic detail, though, in which Troncoso’s genius shined. Every decisive action has a backlash. A general election loomed. If Pinochet went to jail in Spain, the far right could win the election, and roll back the delicate and hard-won transition to democratic rule.

During that historic crisis, Ministro Troncoso came to the Holy Week Retreat at the prestigious Colegio San Ignacio. It was Good Friday. A famous Jesuit with an impressive pedigree would speak to the crowd about the glorious passion and death of an insignificant leftist guerrillero from Galilee. As a new teacher, I got to hand out pointless flyers at the door.

So many carnivores from the aristocratic jungle, gathered together in the classy new gymnasium shouting, crucify him. The stench of expensive perfume and weighty family names stored away for centuries in moth balls overwhelmed the humble senses of Renoleta drivers. The usual gym-shoe fragrance on any afternoon of adolescent boys’ basketball paled by comparison.

All aflutter, Teresita, organizer of the event, came running up in high heels, whispering with patriotic urgency that Raúl Troncoso was outside, and he wanted to talk to me. She imagined everything. That I was the CIA point man, and an important drop was about to be made on the school playground. That the Minister of the Interior needed a trusted translator to communicate with the House of Lords. That I was about to be deported by order of President Frei for high treason. She seemed excited. I told her I could see him in five minutes. When I ran out of flyers.

Raúl Troncoso was not very tall and bald. Beside Frei senior, who loomed extraordinarily tall with feet so big that no shoes purchased in Chile ever fit him, he looked comical. Frei senior gave patriotic speeches to all of Chile from the ancient balconies of power. Troncoso stayed out of view, but he told the President precisely what he had to say and how. Frei’s Cyrano. Politics for Troncoso was like music was to Mozart. He was a genius.

We had never met before. He asked me, you know who I am?

Yeah, I said. Sebastian’s dad. His youngest, Sebastian, sat in the second row of my sophomore English class. The minister and I did not talk about London, Lords or lawyers. He wanted to talk about his kid. The uncanny statesman was also a good father. If all politicians were like that, comrade, the world would be a different place.

Pinochet returned directly to Chile, without passing go, without collecting two hundred dollars. And without stopping in Spain to answer for the very serious charges leveled against him there. The House of Lords had decided to send him to Spain, but the Minister of the Interior got his colleague, the Home Secretary, to intervene. Jack Straw accepted the argument that the Retired General was in poor health and mentally incompetent for trial. And, that Chile was competent to try him on those same counts, exercising the jurisdiction that belonged to the sovereign nation where the crimes had been committed. The arguments seemed to contradict each other, but the Lords liked the part about sovereignty.

Dirty laundry should be done at home. That was a local proverb. That was Pinochet’s defense, and the reason why he came home. The old man arrived at the airport. For the benefit of the press corps, he stood up from his wheelchair, like Lazarus raised from the dead, no longer the drooling idiot the Minister of the Interior had claimed him to be, and marched triumphantly across the tarmac to a waiting bullet-proof limousine. While all the whole wide world looked on in dismay.

Pinochet was insufferable. Eighty-four years old and still messing with the entire planet like a kindergartener urgently in need of a spanking. Faking sick to get out of detention. That’s what we teach in our schools, comrade: Hacerse el huevón. It’s a classic Chilean expression, something like playing the fool. Clever Chileans know how to strategically pretend they are fools to get their way. In England, they called that corruption. In Chile, it was a hand well-played.

The Chilean courts resolved not to prosecute. Again. Pinochet was judged medically and psychologically incompetent. And still in control of dedicated hit-men who didn’t mind arranging accidents for judges and their families. And then, the Retired General, darling boy of all the anti-Castro Cubans, granted an exclusive interview to CNN in Miami. He told María Elvira Salazar of Channel 22 that he wasn’t a dictator, he wasn’t sorry, he was really a very good person, and he had never ordered the murder of anyone. Yeah, right.

Pinochet could have said anything in Miami. He had saved Chile from the Marxist devil, so Cuban expats worshipped the ground he walked on. But, without realizing it, he had stepped in a big stinking pile of fresh wet manure. After the interview aired, the courts in Chile revoked the ruling that had legally proclaimed him a drooling idiot, and they charged him with torture and murder and kidnapping, again. Dirty laundry should get washed at home, but sometimes it gets put away without getting washed at all, and it starts to stink.

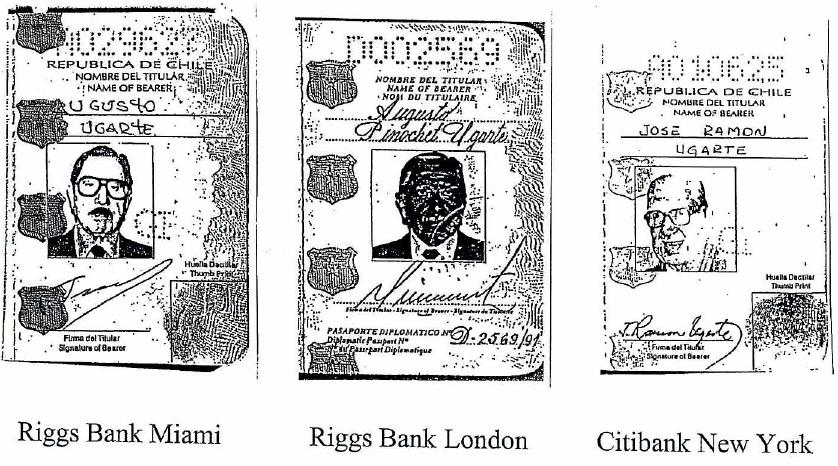

The hidden fact was that not jailing Pinochet was one of the tacit agreements of the transition. His underlings would be charged, and a few of them would even go to prison. Pinochet could be indicted, but not jailed. He died in 2006 with 400 cases pending. And several million dollars on deposit at Riggs Bank in Washington, the origin of which no one could explain.

It wasn’t fair, and everyone knew what was going on. Many questions were left unresolved. It was a tactical retreat on the political chessboard. It had been decided, long ago, before the arrest in London. The victims of the Pinochet government would have to suck it up, and society would turn the page and move on. In the proverbial smoke-filled rooms of traditional power, powerful men of left and right had decided that the mothers of the disappeared would never know the truth, that they would pay the price for peace. We could never know where they were because that would mean we had to recognize how they had gotten there. We were to proceed as if nothing had ever happened. We were supposed to just collectively play the fool.

Chess is the ultimate Masonic power game. In Uruguay, masonic institutions—basically, all institutions—give not-so-subtle signs of their lodge affiliation by installing black and white tile in the entryways. In the form of a chessboard. On which you are required to stand. So that you will never forget that it is the kings and queens and bishops who make the power moves, and that pawns like you exist to get sacrificed.

Pinochet was a Freemason. Allende was, too. They belonged to the same lodge and that was the reason that Allende selected Pinochet to be his Commander in Chief. It wasn’t about his politics. The Chilean military, traditionally, didn’t have politics. Allende chose Pinochet because of the undying personal loyalty expected of fellow lodge members.

It could be assumed that, after the coup, because of his betrayal, Augusto was no longer welcome in the lodge. But of course, by then, he didn’t need a lodge. By then, he had all the powerful connections he would ever need. He had the GCU, the CIA, and the Opus Dei.

Some think that Opus Dei was the traditionalist Catholic response to the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. Too much social doctrine, they said, not enough Latin, incense and fancy robes. After the Council, Opus did call for a return to strict observance. But the Opus Dei predated the Council. It was the Catholic backlash to Spanish Freemasonry.

Before the Spanish Civil War, Freemasons had carefully situated themselves in strategic positions. They controlled commerce, public administration and education. Except for a few who managed to escape on ships bound for Chile and Uruguay, all Spanish Freemasons—all of them Republicans, which in Spain in 1930 meant, Marxists—were lined up against brick walls and shot by Franco’s men. To save Spain, the monarchy and the Catholic church, they said.

Spanish society was left without technocrats, civil servants or teachers. They asked themselves, how can we fill all those slots, and guarantee a Catholic, conservative, traditional Spain for the rest of eternity? And Opus Dei was born. Literally, the work of God. It functioned on the model of Freemasonry—a network of connections, invisible to non-members, set on controlling everything that counts—but with sacraments. Bishops moved across the board diagonally, comrade, but they always stood beside the king and queen.

From the beginning, Opus Dei in Chile latched onto the Pinochet government. It grew and became powerful. Augusto knew the drill. He had been a Mason for a long, long time. With a pinch of incense offered to the statue of the Immaculate Conception, he could gather the entire flock into his corral and confirm them as Chile’s rightful ruling class. He needed them because the CIA would grow tired of him, eventually, and he knew it.

Christian Democrats did not run with Freemasons or Opus Dei. So, why did Raúl Troncoso play chess with them? Why didn’t he recommend to Eduardo Frei that the House of Lords be allowed to make their own aristocratic decision and let Pinochet be someone else’s problem for a while? In Spain, guilty memories from Franco’s regime—and the conquest of the New World—needed purging. Pinochet would have gone to prison. It sure would have felt good.

It looked terrible for Troncoso, flying back and forth to London to defend the tyrant. But he wasn’t running for office. He insisted that Frei’s government should do everything possible to keep Pinochet out of Spain, and it wasn’t even to protect the international image, so all-important for tourism and foreign investment. It was because he knew that the elections in ’99 were going to be close. And he was right. It was a real nail-biter. If Pinochet had been jailed in Spain, patriotic moderates would have run to the polls to vote for UDI, the party of Pinochet’s Opus Dei.

It wasn’t about compassion for an octogenarian. It was about patriotism. Chileans distrusted foreigners in general. Too many centuries spent in isolation, living far across the sea and behind the tall mountains. But what really got them going, aside from fútbol matches, was the notion of being treated like savages. Como indio, as they would say. The key detail was that Judge Baltasar Garzón from Spain had argued before the House of Lords that Pinochet could never receive a fair trial in Chile. Which was true. That has already been decided.

In Spain, the assumption was that he still had a lot of residual power in Chile. That was true, too. He had power over courts and judges and lawyers. People were still afraid of him, and rightly so. But what voting Chileans heard was that a Spanish judge said that Chileans are too uncivilized to hold a fair trial. That would have made good people of moderate leanings vote for the extreme right. Troncoso had picked that up, and he had figured out a way to bring Pinochet home. Tío Augusto would have his moment at the airport, but nobody would care after that. Or so he hoped. Chess was not a religion for the Christian Democrats, but they did know how to play.

Raúl Troncoso died of cancer in 2003. It was an insidious type of cancer that hides in your guts until it’s too far along to do anything about it. He was sick for a few months, and he died at home. It wasn’t in the news until he was dead. Like Popes in the Vatican, who are always in perfect health until they are not breathing anymore. Sebastián knew his father was dying. He asked me to please keep it a secret, which I did. He missed his dad, after that. Raúl Troncoso was a wonderful father, a shrewd politician, and a courageous patriot, in his most clever way.

Chile’s wounds have yet to heal. The pawns on the chessboard still get played, but good people do what they can. They hope for the day when someone can do more.

Born in Texas, Nathan Stone lived more than thirty years in Chile. He is now back in Austin, working on a dissertation about Chile, and how we remember the revolutionary years.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.