The success of Not Even Past is made possible by a remarkable group of faculty and graduate student writers. Not Even Past Author Spotlights are designed to celebrate our most prolific authors by bringing together all of their published content across the site together on a single page. The focus is especially on work published by UT graduate students. In this article, we highlight the numerous contributions to the magazine made by Nathan Stone.

Nathan Stone is a Ph.D. candidate in Latin American History. Texas-born and raised, he ventured into the wilds of Indiana for undergraduate work in English at the University of Notre Dame, graduating in 1979. After that, with a brief pause in 1986 to eke out a Masters in English right here at UT, he lived and worked in Chile, Uruguay, and Brazil for upwards thirty years. In Chile, during the dark years of the Pinochet regime, he became friends with the Association of the Families of the Disappeared. Before they were taken, many of the desaparecidos had belonged to MIR, Chile’s youthful “Movement of the Revolutionary Left”. Nathan now researches the allure of New Left revolutionary movements in Cold War Latin America. And sometimes teaches undergrads to conjugate their verbs in the Spanish department.

For the plebiscite of ‘88, Chile had its first political campaign in fifteen years. La Campaña del NO tried to make it fun. We all had many dark tales to tell, and maybe a moral obligation to tell them, but sad stories don’t get votes. Moreover, a very fine line, invisible to carabineros, divided protesting and campaigning. Opposition supporters had to resort to clever strategies. We would drive around with their windshield wipers on, on a dry day. Like saying “no” by moving your index finger from left to right. The cops couldn’t exactly arrest you for using your windshield wiper.

If you had to use the horn, the cadence was ta-tá, ta-tááá. It sounded like the slogan, y va caer—literally, it’s about to fall—the wishful refrain that had been around since the ‘70’s, calling for the military government to implode. Our efforts fell short of actual revolution, but we had to start somewhere.

Read the full article here.

I remember the stink of the fishmeal plants in Iquique. During the austral winter of 1983, the vapors that turned tons of whole anchoveta into high protein fish flour lingered over the beach with the coastal fog until the customary afternoon breeze came and carried it away. Local residents called it “the smell of money.” Domestically produced fish flour had become the primary source for fish food in the new salmon farms that had begun to scar the pristine beauty of the lakes and fiords in the Chilean south. It would also become dog food, and the “high protein cookies” on school lunch menus for the undernourished children that General Pinochet’s second recession in ten years had pushed dangerously down the path of deficiency disease. But the smelly fishmeal extracted from the seemingly infinite Pacific coast of northern Chile had already become a vital element in an increasingly global ecosystem of profit-driven food production. Economists and technocrats called it a “non-traditional export.” Along with the farmed salmon, the fresh fruit out of season and the world’s finest red wines for a little less money, Chilean fishmeal would help reduce the local economy’s absolute dependence on the roller coaster of international copper prices. It would fatten pigs in Germany and chickens in California to satisfy the voracious appetites of a competing species now referred to simply as “the consumer.”

Read the full review here.

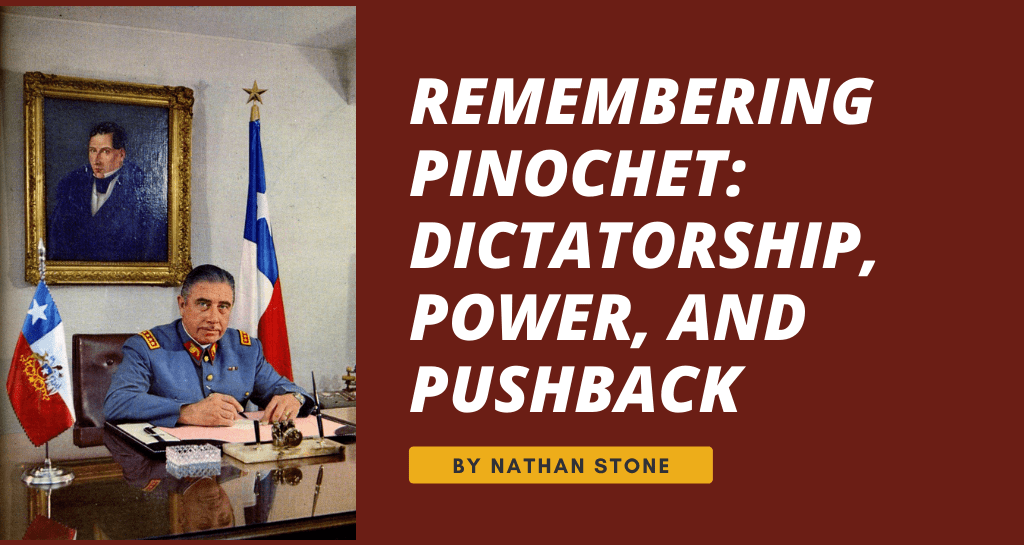

Official tallies put the death toll inflicted by the Pinochet regime in Chile over three thousand, while the imprisoned and tortured numbered over thirty-eight thousand. Not to mention almost two hundred thousand, one in every fifty Chileans, who went into exile. Staggering as those numbers might be, such statistics represent but a fraction of real victims. Most of the dictatorial blowback happened under the radar, in the clandestine shadowlands of the rural backcountry and deep within the interlocking borders of peripheral urban shantytowns, Chile’s poblaciones. There, resistance was subtle, solidarity was key, and no record survives. Chileans without friends in high places, those who lost their hearts, their hopes, and their lives in those forgotten corners, live on only in the memories of their friends, families, and neighbors.

Read the full article here.

They weren’t all the same. We know of at least one soldier who had a conscience. There were several, actually. Most were weighty figures, captains and colonels who refused to follow orders. Some of them quit or went into exile. Others died. But I’m talking about conscripts, the powerless boys who were in military service when the decision was made to interrupt the institutional process of the Chilean state on September 11, 1973. When the elected socialist government of Salvador Allende was overthrown by the US-backed Chilean military. When those boys were commanded to arrest, torture, and kill their own brothers and sisters.

Rodolfo González was one such conscript. He was proud that he had been chosen for the Air Force. He was just eighteen. After the coup, he was commissioned to serve at the DINA, Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional. That was General Pinochet’s secret police.

Rodolfo wasn’t an agent, but he did participate. He had guard duty. He delivered messages. He got coffee for the boss when the boss got tired of torturing someone.

Read the full article here.

Rodolfo Müller is almost a hundred years old, now. He still lives in the same house as always, off Simón Bolivar, between Hamburgo and Coventry. That’s in Ñuñoa, a township on the near west side of Santiago. It’s a big house, and very nice but unpretentious. If he had wanted, he could have picked a more prestigious address further north, in Providencia, or up higher, in Las Condes. But he didn’t.

Rodolfo was born in Germany in about 1920. Before World War II, he came to Chile with his parents and his brother. They were just teenagers. I met him when he was almost sixty. He still looked very German after all those years: tall, blond, and blue-eyed. But he was a Jew. That’s what people said, anyway. Maybe, just on his mother’s side. They came to Chile to escape from Hitler. They left in time and made new lives in South America.

Read the full article here.

A romero is a pilgrim, comrade. I guess we are all pilgrims, to some degree, though some pilgrimages seem to go on forever, while others end abruptly.

When Pope John Paul II came to Chile in April of ’87, the local church tried to script his visit. They wrote him a theme song and they played it non-stop the whole week: Messenger of life, pilgrim of peace. But John Paul was no friend of solidarity, human rights or poor people who got organized. That was all communism to him. Polish Jesus hated communists. The Holy Father’s Messiah became flesh and dwelt among us to impose order on a chaotic world with neoliberal capitalism, an M-16 and logistical support from the CIA.

Ex officio, the Pope aligned himself with authoritarian figures, especially if they seemed anti-communist. That didn’t square with the worldly politics of the Second Vatican Council, and he knew it. He had done everything in his power to roll back the Council, to mystify the crowds with papal pageantry and impose his moral authority using a constant, authoritative threat of hell. The way it used to be, in the good old days.

Read the full article here.

Pampa Unión, today, is a ghost town lost in the Atacama Desert, a mile high and halfway between the Chilean mining centers of Antofagasta and Calama. Founded over a century ago as a medical way station, it quickly became a resting place for nitrate miners on their days off, complete with all the supplies and entertainments that working men required. With two main streets and just one tree, the 2,000 stable inhabitants entertained a floating population of up to 15,000. The town was abandoned in 1954. All that is left today are the ruins of adobe walls with broken bits of signage and a cemetery.

Read the full article here.

Colegio Andacollo was a K-through-12 parish school in old town Santiago. The Holy Cross Fathers took it as their new mission when the military government kicked them out of Saint George’s, their traditional academy for the elite. Andacollo was another world.

The original Andacollo was a mountain town in the north where Our Lady of Deep Rocky Mines granted solace and safety to her devoted followers. Our Andacollo was on the corner of Mapocho and Cautín, in a barrio of old multifamily dwellings, cheap bordellos, and the local seafood market. The place had a history of union struggle, fiery passion, and a profound commitment to the miracle-working Virgin of Andacollo. It also had a secret tale of tragedy.

Read the full article here.

I started going to camp in 1968. We were still just children, but we already had Vietnam to think about. The evening news was a body count. At camp, we didn’t see the news, but we listened to Eric Burdon and the Animals’ Sky Pilot while doing our beadwork with Father Pekarski.

Pekarski looked like Grandpa from The Munsters. He was bald with a scowl and a growl, wearing shorts and an official camp tee shirt over his pot belly. The local legend was that at night, before going out to do his vampire thing, he would come in and mix up your beads so that the red ones were in the blue box, and the black ones were in the white box. Then, he would twist the thread on your bead loom a hundred and twenty times so that it would be impossible to work with the next day. And laugh. In fact, he was as nice a guy as you could ever want to know.

Read the full article here.

When I was very small, I lived six blocks from the Santa Fe Opera. Our home was in the Tesuque Village, which is really just a country road that runs alongside the Tesuque Creek just north of Santa Fe, with twenty tiny cul-de-sacs stretching up into the alluvial crannies of the southern Rockies. There were fruit stands and general stores. The Indians from the Tesuque Reservation would come to trade hides for cigarettes. This was before there were casinos. I remember the taste of the fresh local pears. There will be some in heaven, I assume. Once, I got lost. I was three. An Indian from the reservation took me to every house in the village and asked me, “Is that your house, little boy?”

On the horizon to the east, we had the Sangre de Cristos. They were huge, daunting, legendary and high. Mountain snow accumulated there in the winter to keep the semi-arid New Mexico wasteland inexplicably green all summer. Deep in the heart of the wilderness, at Horsethief Meadow, the early Comanche hid away in the lush green grass of summer with the wild and not-so-wild herds of mustangs that made them the wealthiest traders at the Taos market in the nineteenth century. Savages? Trade in your textbook. They knew more about selective breeding than Her Majesty’s Master of Horses.

Read the full article here.

I remember Georgia O’Keeffe. I couldn’t have been but three, first time I met her. She was already an older woman by then, or late middle age, at least. She was tall and perfectly centered, with a slender frame and grey hair pulled back in a tight bun. She wore long sleeves and dark jeans. She smoked only the best Cuban cigars. Women weren’t supposed to smoke cigars at all. But she got away with it. She and Frida Kahlo.

Miss O’Keeffe got her smokes from La Habana. They were already hard to get in ’61. The trade embargo was not yet in place, but things were already getting sticky with Fidel. The State Department didn’t like the combat fatigues, and the mob wanted their casinos back. I think they drove Fidel into Soviet arms. After that, Ché Guevara went to Angola, with a habanero in his teeth, just like Miss O’Keeffe. Cuban cigars became contraband. Reserved for drug traffickers and CIA agents. I suspect Miss O’Keeffe had some stashed away for a rainy day. But in the summertime, it rained every afternoon on the high plains of New Mexico. You learned to bide your time. You knew that’s just the way it was going to be.

Read the full article here.