In honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, the 2022 Lozano Long Conference focuses on archives with Latin American perspectives in order to better visualize the ethical and political implications of archival practices globally. The conference was held in February 2022 and the videos of all the presentation will be available soon. Thinking archivally in a time of COVID-19 has also given us an unexpected opportunity to re-imagine the international academic conference. This Not Even Past publication joins those by other graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin. The series as a whole is designed to engage with the work of individual speakers as well as to present valuable resources that will supplement the conference’s recorded presentations. This new conference model, which will make online resources freely and permanently available, seeks to reach audiences beyond conference attendees in the hopes of decolonizing and democratizing access to the production of knowledge. The conference recordings and connected articles can be found here.

En el marco del homenaje al centenario de la Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, la Conferencia Lozano Long 2022 propició un espacio de reflexión sobre archivos latinoamericanos desde un pensamiento latinoamericano con el propósito de entender y conocer las contribuciones de la región a las prácticas archivísticas globales, así como las responsabilidades éticas y políticas que esto implica. Pensar en términos de archivística en tiempos de COVID-19 también nos brindó la imprevista oportunidad de re-imaginar la forma en la que se llevan a cabo conferencias académicas internacionales. Como parte de esta propuesta, esta publicación de Not Even Past se junta a las otras de la serie escritas por estudiantes de posgrado en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. En ellas los estudiantes resaltan el trabajo de las y los panelistas invitados a la conferencia con el objetivo de socializar el material y así descolonizar y democratizar el acceso a la producción de conocimiento. La conferencia tuvo lugar en febrero de 2022 pero todas las presentaciones, así como las grabaciones de los paneles están archivados en YouTube de forma permanente y pronto estarán disponibles las traducciones al inglés y español respectivamente. Las grabaciones de la conferencia y los artículos relacionados se pueden encontrar aquí.

Early modern European intellectual heroes like Bacon and Hobbes popularized the idea that ‘knowledge itself is power.’ Historian Arndt Brendecke’s exploration of the 16th-century Spanish empire calls this trope to task by asking a simple question that is difficult to answer: to what extent was knowledge the basis of Spanish colonial power? Born in Bavaria and educated in the densely theoretical German scholarship, Brendecke published his masterpiece, The Empirical Empire: Spanish Colonial Rule and the Politics of Knowledge, in 2016. This book offers conceptual contributions to the fields of archival studies and Latin American history in ways that help frame the core themes of the 2022 Lozano Long Conference, “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives.”

Brendecke’s work helps us rethink colonialism through the archival production of information from and about the New World. His book provocatively argues that the massive amount of paperwork collected from colonial Spanish America was not a sign of an omnipotent state that knew its subordinate populations and territories as the myth of absolutism would have us believe. In fact, it was quite the opposite. Instead, overwhelming amounts of paperwork show the political blindness and ignorance of Spanish rulers. Brendecke carefully disentangles archives from vigilance, knowledge from information, and “rational” government from patronage networks to prove his case.

Historian Fernand Braudel promoted the image of the Spanish monarchy as a sort of spider spreading out an extensive web woven out of meticulously notarized papers: millions of them. However, the Crown’s supposed ubiquity, omnipotence, and omniscience in its dominions are not what the archival record shows. The Crown and its institutions faced the challenge of long-distance rule. Despite sponsoring many projects to understand its territories better, colonial accounts of what was happening in the New World were highly mediated by the particular interests of those Spanish settlers informing the Crown. Brendecke highlights thousands upon thousands of archival texts. They reveal how conflicts among Spanish Americans of different backgrounds colored their attempts to persuade the king of reliable information while seeking to undermine the reputation of their opponents. As a result, the monarch could not see or know the New World as it was. Instead, he controlled his subjects by trusting the ones he perceived as loyal. According to Brendecke, colonial power was based on partialized loyalties and exchanges of favors appearing in documents as information, but this information by no means represented knowledgeable, objective reports.

While a significant portion of the historiography of knowledge explores its creation as a translation of raw, subjective data into reliable, objective understandings, Brendecke complicates this assumption. By focusing on a world of actors with interests, he reveals that the Braudelian spider web was the façade that could not perceive its dominions objectively. Interests create blindness and ignorance in Brendecke’s model, but rather than obstructing the exertion of power, this dynamic was how colonial rule worked. Therefore, Spanish epistemological and political claims on the Americas involved archiving demands and petitions of favors to monarchical institutions. As a result, Spanish colonial rule was based less on acquiring objective knowledge and more on its ability to receive, archive, and adjudicate conflict among those who clamored for favors from the Crown.

Brendecke builds upon a Foucauldian idea: early modern societies experienced a “governmentalization” in which medieval pastoral knowledge/power technologies such as the inquisitorial procedures were gradually adapted and implemented for ruling states. This view enables him to connect knowledge and power through vigilance, and, in doing so, he reconceptualizes both. Inquisitors, for instance, were not the only ones who surveilled communities. Community members watched their fellows’ behavior and denounced them when convenient. For example, if some priests of a given region were to denounce local rulers for their corrupt actions in the Spanish empire, the Crown would increase their control over these subjects by receiving their denunciations and making decisions based on trust, loyalties, and favors. That is what Brendecke calls the “triangle of vigilance,” which shows both the flows of information and the ways the monarchy ensured its power despite “not knowing.”

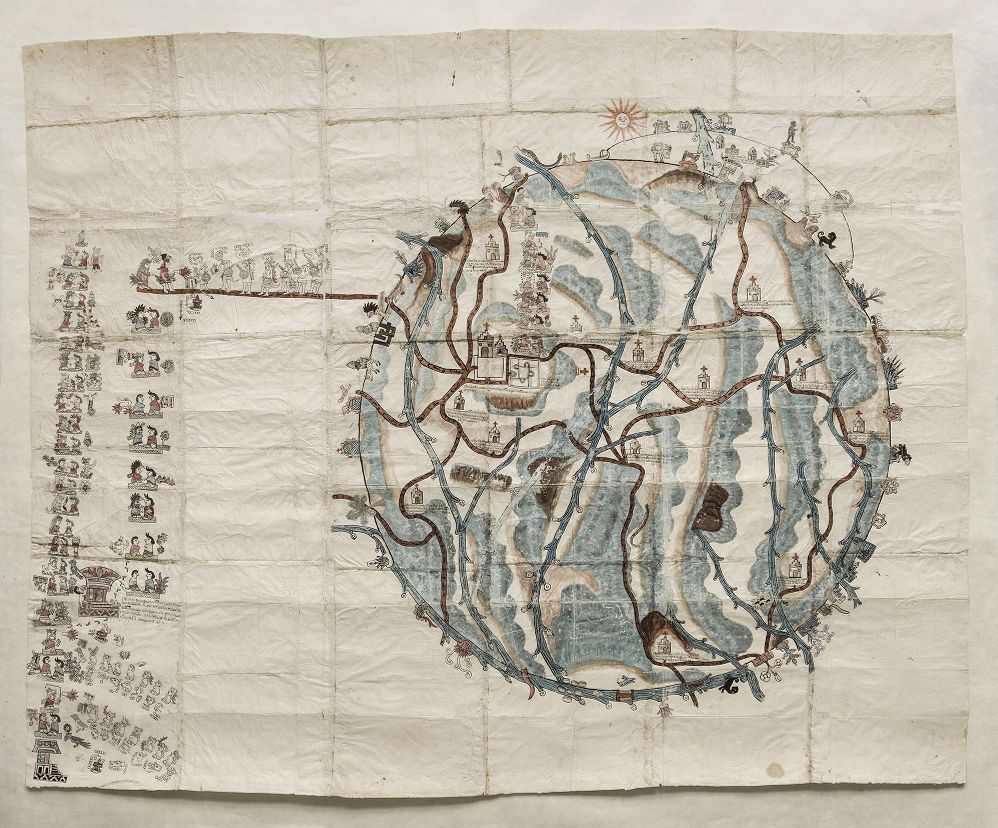

Arndt Brendecke recognizes some efforts to centralize and systematize information in the Spanish empire, such as forming a state archive and institutions like the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade). However, centering too much on these institutions may overestimate the royal mandates while underestimating Spanish America’s role in producing information. The peninsular archival institutions did not work as ‘centers of calculation’ despite stockpiling documents because processing that massive amount of paperwork was not viable. Brendecke focuses on the 1570s and 1580s, during Juan de Ovando’s presidency in the Council of the Indies. At that time, several laws for compiling all the information possible (entera noticia) emerged, with projects like the Relaciones Geográficas. However, for Brendecke, Ovando’s reform was unsuccessful in making a more “rational” state. On the contrary, they merely reflected the expansion of patronage networks into the Atlantic world, where decisions were based on loyalties instead of knowledge. It meant that the Crown was incapable of effectively understanding the New World’s territories and populations. However, by focusing too much on the discordance between intentions and results, might this be a teleological reading of Spanish knowledge projects? After all, reading the documents from a peninsular lack of instrumental use elides the actual participation of local populations in creating knowledge about the New World.

The Empirical Empire draws on and contributes to significant debates regarding the emergence of modern states, long-distance government, early modern empiricism, the history of archives and information, bureaucratic rationalities, and patronal clientelism in Spanish America. By focusing on actors, actions, and means (information registered in documents) rather than abstract ideas and laws, Brendecke realistically evokes Spanish rulers in Iberia and the Americas as people with ambitions and vast networks of allies and enemies.

In short, Brendecke opens the black box linking archives to social networks, thereby revealing the value of teasing out how people’s interests and influences shape the transformation of information into power. In doing so, he offers a substantial contribution to our understanding of 16th-century Spanish rule over the Americas, certainly breaking the trope that information and knowledge are actual colonial power. Brendecke’s opening leads to a logical follow-up question: to what extent might this model of ‘agnotology’ (the study of ignorance) apply to other early modern imperial regimes? Avoiding this question would force our continued blindness to how other early modern imperial monarchies may have been as blind and patronal as the Spaniards in their colonial efforts. At the end of the day, long-standing Eurocentric views of Spanish American societies have, at best, characterized them as spaces of epistemological backwardness or, at worst, portrayed the region as riddled with clientelism and ignorance perpetuated by caciques and caudillos—traditional and charismatic leaderships in Weberian terms. Researchers should also take care when considering the imperial context within which Brendecke’s model may or may not apply or risk reproducing traditional prejudices regarding the geopolitics of knowledge production relevant to understanding present political contexts in Latin America.

Suppose we reduce the agency of the European, Indigenous, African, and mixed-race people to their struggles of interests, production of blindness, and instrumental rationality. Where does this model leave space for the Latin American peoples’ cultural, epistemological, and ontological diversity and creativity? Postcolonial approaches may indeed have overvictimized subalterns of our continent when arguing for the “epistemicide.” Claiming ignorance as the core component at work in Spanish colonial rule leaves unexplained the processes by which inhabitants of Latin America have creatively ruled and known their own local contexts. Indeed, knowledge is not automatically power, but a more nuanced view of what knowledge is, beyond objectivity and empiricism, may demonstrate that subjects and rulers in Spanish America were anything but blind and ignorant. In fact, we may discover that curiosity, intercultural entanglement, and even cooperation were significant catalysts for the production of knowledge, perhaps at times more so than interpersonal conflicts and distrust.

Rafael Nieto-Bello is a second-year Ph.D. student in the Department of History at UT Austin. He obtained a double B.A. in History and Political Science and a double minor in Philosophy and German Language in the Universidad de Los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia, 2018). In 2021, he was awarded the Fellowship on “Race and Caste” from the Institute of Historical Studies (IHS) for preparing a grant proposal. Additionally, he obtained the Lozano Long Centennial Fellowship from LLILAS Benson for the coordination of the 2022 Lozano Long Conference “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives.” His research is a history of knowledge from the 16th-century Spanish municipalities. He explores how town communities from diverse ethnic backgrounds described and claimed to know their populations and environments through corporate efforts placed on the local councils.

Works Cited

Brendecke, Arndt. The Empirical Empire: Spanish Colonial Rule and the Politics of Knowledge. Berlin, [Germany]; De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2016.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.