By John Gleb

The American foreign policymaking establishment has a diversity problem. The problem is so serious that it has spawned its own in-joke, which mocks top American diplomats for being “pale, male, and [educated at] Yale.” Statistics back up this stereotype. According to a recent audit conducted by the Government Accountability Office, leadership cohorts at the State Department and within the Foreign Service are overwhelmingly white and overwhelmingly male—far more so than the workforces they oversee or the public they serve. Even more alarmingly, since the audit’s publication in February 2020, frustrated Foreign Service officers have provided journalists with ample evidence of systematic discrimination against diplomats of color. Contributors to the Harvard Kennedy School’s LGBTQ Policy Journal have also raised concerns about the status of LGBTQI+ State Department personnel, faulting both the Department and Congress for ignoring their needs and contributions.

To their credit, thought leaders and government officials have responded to this fiasco by embracing reform. They have also adopted a striking slogan to justify their renewed interest in diversity. “Representatives of US foreign policy need to look like America,” declared the American Academy of Diplomacy in June 2020. “A truly great nation draws strength from all of its citizens.” The same phrase—“America’s Diplomats Should Look Like America”—headlined a December 2020 op-ed penned by Representative Barbara Lee (D-CA), co-sponsor of a bill designed to make the Foreign Service “representative of the American people” by diversifying its membership. Major studies sponsored by Harvard University, the Council on Foreign Relations, and the Truman Center for National Policy have deployed strikingly similar language in defense of proposed diversity reforms; so, too, did the Biden Administration’s Interim National Security Guidance, which promised “urgent action to ensure that our national security workforce reflects the full diversity of America.” Senior diplomats have joined the chorus as well. “The State Department has the honor of representing the American people to the world,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken noted in a press release last February. “To do that well, we must recruit and retain a workforce that truly reflects America.” Blinken made the same point a few months later when he announced the appointment of his Department’s first Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer. “America’s diversity is a source of strength that few countries can match,” the Secretary of State asserted. “[W]hen we fail to build a team that reflects America, it’s like we’re engaging the world with one arm tied behind our back.”

Whether Blinken and his colleagues will follow through on their commitments to diversity remains to be seen, but the rhetorical framework they have built around those commitments is a significant innovation in its own right. Although State Department officials have long believed that American diplomats should “look like America,” they have also struggled to reconcile this conviction with the reality of American social and cultural diversity. For decades, Department officials posited the existence of a single American national identity manifested uniformly throughout the United States. Their insistence on securing authentic diplomatic representation for an imagined, supposedly homogeneous American people did nothing to promote diversity. Instead, it worked to exclude members of historically marginalized communities—including women, people of color, and LGBTQI+ Americans—from the Foreign Service.

Exclusionary nationalism was certainly not the only barrier that confronted marginalized individuals who tried to find space for themselves inside the Department. Throughout the twentieth century, chauvinistic masculinism, white supremacy, and homophobia played key roles in shaping both the institutional culture of the American foreign policymaking establishment and the political culture of the United States more broadly. Nevertheless, an examination of the State Department’s unique history reveals an ironic truth: the conviction that American diplomats should “look like America,” now the driving force behind diversification, once justified discrimination.

In Search of “Plain American Gentlemen”

During the nineteenth century, conventional wisdom in the United States held that diplomats were effete, snobbish aristocrats, out of touch with the needs and mores of ordinary citizens. For this reason, as the historian David Nickles has shown, American political leaders routinely demanded that their representatives abroad affect mannerisms consistent with their country’s “republican simplicity,” dressing in plain clothes and ignoring conventional diplomatic etiquette. Hostility to European-style professional diplomacy waned during the 1890s, by which time the American republic was an emerging world power. Nevertheless, at the turn of the twentieth century, American diplomats still found themselves struggling to swim against the tide of popular prejudice. In 1909, Assistant Secretary of State Huntington Wilson spoke for many of his colleagues when he complained about the sizable number of Americans who imagined diplomats to be “creatures fashionably attired (preferably in gold lace exclusively), . . . hobnobbing with royalty and aristocracy, quarreling about precedence, and gossiping at afternoon teas . . . , bowing beautifully and speaking foreign languages well, while forgetting their own.”

Wilson was one of a small number of reformers who were determined to bring American diplomatic practice up to European standards during the early 1900s. In order to legitimize their endeavors, he and his colleagues developed their own vision of a model diplomat: “a plain American gentleman,” Wilson explained, “who sets right values on things, avoids affectations, and eschews ostentation.” This vision wasn’t just for show. It also influenced the development of new screening examinations for the professionalized consular and diplomatic services—precursors to the modern Foreign Service Exam. An administrative board tasked with designing a prototype exam for the consular service concluded that future examiners would have to identify “certain native qualities” in candidate consuls that were “[n]ot less, but rather more important” than their professional qualifications. According to the board, a “high-grade consular officer” needed to be “first of all a loyal, patriotic American citizen, . . . a representative young man of our country.” Meanwhile, the board responsible for administering the new diplomatic entrance exam fell under Wilson’s personal direction, with predictable results. In May 1910, the Assistant Secretary of State and his fellow examiners took a candidate diplomat to task for being “unduly affected with foreign ways” and having “an exaggerated idea of the importance of ‘society’”—he was “probably rather a snob,” the examiners concluded. Another, similar candidate was likewise deemed “[m]uch too foreign in appearance and manners.” The examiners’ prescription: “[he] should be sent to a post . . . where the influences were ultra-American.”

Beneath the melodramatic references to loyalty, patriotism, and “ultra-American” influences, there lurked a dangerous assumption, which reformers like Wilson helped establish in the minds of their successors. State Department officials now imagined that they could identify a unique set of social and cultural traits (the “right values” or “native qualities”) that distinguished authentic Americans from unrepresentative aliens. The problem, of course, lay in determining what those traits were, and predictably, the Department’s solution involved “othering” people who had been excluded from mainstream American society. Foreign aristocrats were an obvious and necessary foil for American diplomats desperate to win the public’s trust. But diplomats also sought to categorize and define themselves in opposition to socially marginalized people living within the United States. As a result, throughout the twentieth century, the State Department reproduced and institutionalized a revealing array of racist, sexist, and homophobic stereotypes.

“Repugnant to the Folkways and Mores of American Society”

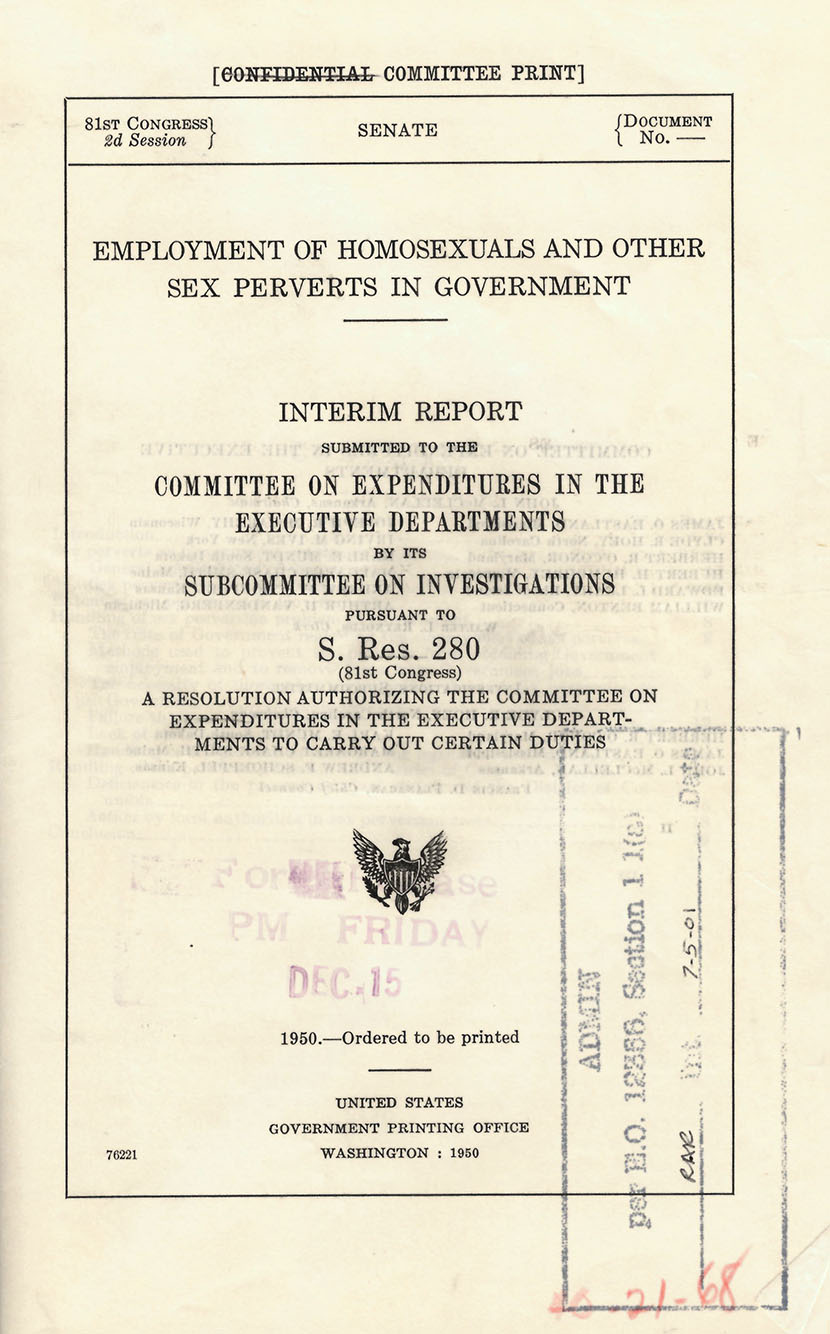

A single, dramatic example will suffice to show just how damaging those stereotypes could be. In 1947, at the dawn of the Cold War, the State Department adopted new internal security protocols and empowered a team of investigators to enforce them. They did so at a pivotal moment in American social history. Since the early twentieth century, government agencies in the United States had grown increasingly invested in policing sexual activity, and by the 1940s, many officials considered homosexuality irreconcilable with good citizenship. Top American diplomats followed suit. Acting partly in response to pressure from Congress, they classified “sexual perversion” as a potential threat to national security.

It was a fateful decision. When the full extent of the State Department’s antigay investigation became public knowledge at the beginning of 1950, a tidal wave of homophobic paranoia—a “Lavender Scare” to rival the contemporaneous Red Scare—swept through federal, state, and local bureaucracies all over the United States. The Lavender Scare’s impact on the foreign policymaking establishment was particularly devastating. For the next two decades, gay State Department personnel endured overt, systematic persecution, and according to LGBTQI+ advocacy groups, institutionalized homophobic discrimination quietly continued inside the Department until the early 1990s.

The complexity of the Lavender Scare defies monocausal explanation. It is clear, however, that the State Department considered the marginal social status of LGBTQI+ Americans to be dangerous in its own right. In a notorious June 1950 report on the progress of the Department’s internal investigation, Assistant Secretary of State Carlisle Humelsine argued that gay men and women were “undesirable as employees” because their transgression of mainstream American social norms stunted their personal and political development. Humelsine’s report played up the abnormality of gay sex, claiming that it involved “acts of perversion . . . abhorent [sic.] and repugnant to the folkways and mores of American society.” It also made note of the gay community’s social isolation and reflected on its supposedly debilitating psychological effects. “We believe,” Humelsine warned, “that most homosexuals are weak, unstable, and fickle people who fear detection and who are therefore susceptible to the wanton designs of others.” State Department investigators had not, in fact, discovered any evidence that gay Foreign Service officers were being blackmailed or manipulated into disloyalty. Nevertheless, Humelsine concluded that the “character weaknesses” he speciously associated with social marginalization made “the known homosexual . . . unsuited for employment” in his department. Absurd though such statements may have been, during the 1950s and 60s, they justified the termination of about a thousand of Humelsine’s colleagues and subordinates.

Confronting the Mistakes of the Past

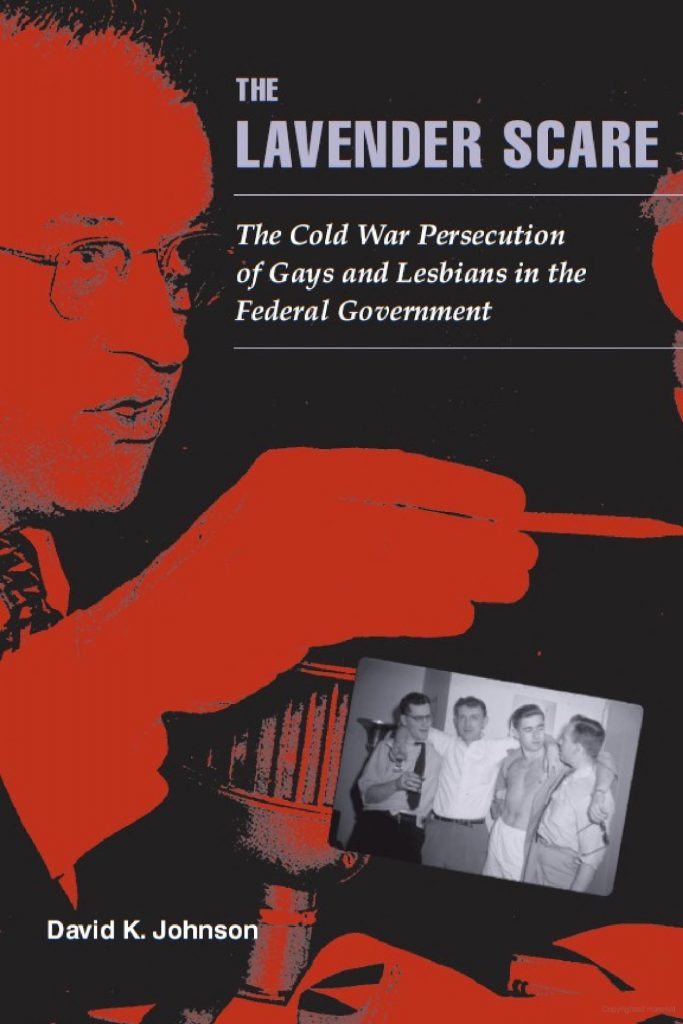

It took half a century for the history of the Lavender Scare to become widely known and even longer for the State Department to begin exorcising its demons. External pressure from concerned federal legislators has played a key role in encouraging the Department to act. So too has the work of historians like David Johnson, the author of a landmark 2006 book entitled The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government. Citing Johnson’s book, Senator Ben Cardin (D-MD) asked then-Secretary of State John Kerry to issue a formal public apology on behalf of his department in November 2016. Two months later, Kerry obliged, releasing a written statement that constituted the first official acknowledgment of the federal government’s complicity in the Lavender Scare. “The Department of State,” the statement explained, “was among many public and private employers that discriminated against employees and job applicants on the basis of perceived sexual orientation” during the Cold War. “These actions were wrong then, just as they would be wrong today.” At a Pride Month event last summer, Assistant Secretary of State Wendy Sherman went further, noting with regret that her predecessors had been “especially aggressive” in their persecution of LGBTQI+ personnel. As Sherman spoke, a Pride flag, raised in honor of the Lavender Scare’s victims, fluttered above the State Department’s headquarters in Foggy Bottom for the first time in its history.

It is tempting to interpret all these apologetic statements and the commemorative ceremonies as reassuring proof that the American foreign policymaking establishment, having finally owned up to its mistakes, is now marching inexorably towards a kinder, gentler future. But treating the past like a measuring post for progress isn’t likely to teach us very much about the root causes of the problems we want to solve, nor is it likely to help us solve them. A much more comprehensive reckoning with the State Department’s shameful history is in order.

Administrative history is useful insofar as it forces us to confront an uncomfortable reality: institutions, especially old ones, have a way of defying the best intentions of their own leaders. Bad administrative outcomes aren’t necessarily born of malice. Sometimes, they’re the products of seemingly innocuous routines, invented long ago to perform tasks we would now deem absurd or unsavory. It is up to us to assign our institutions new and better tasks, and if we want to see those tasks accomplished, we must be prepared to ruthlessly interrogate the underlying assumptions that determine institutional behavior.

“We must finally ensure equitable career outcomes for all of our employees,” declared Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley, the State Department’s new Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer, during her appearance at the Pride Month ceremony last summer. “This means we confront the mistakes of the past head on.” A few moments earlier, Abercrombie-Winstanley had committed herself to ensuring that the cohort of diplomats under her charge “comes to look like the country we lovingly represent.” Understanding the fraught history of this phrase helps underscore its significance—and it also suggests a course of action in which every American citizen has a part to play. Only by collectively celebrating our country’s diversity can we hope to make sure that inclusion, rather than discrimination, remains the guiding principle behind the State Department’s long search for diplomats who “look like America.”

John Gleb is an America in the World Consortium Pre-Doctoral Fellow at the Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs in Washington, D. C. He is also a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin, where he earned his MA in May 2020. John received his BA at the University of California, Berkeley, from which he graduated with High Honors and Highest Distinction in 2017. At UT, he is a Graduate Student Fellow at the Clements Center for National Security and has appeared as a guest on The Slavic Connexion, a podcast affiliated with the Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies. He is also fluent in French. John’s research focuses on the rise of the American national security state and on the relationship between foreign and domestic politics in the United States. He is especially interested in the concept of political consensus, a yearning for which has decisively shaped the worldview and activities of American foreign policymakers since the turn of the twentieth century. John’s dissertation will examine attempts to forge a foreign policy consensus both inside and outside the halls of government between 1900 and 1950. Thanks to those early consensus-building campaigns, the national security state that emerged during the Cold War would consist of more than just a cluster of institutions: as John will show, it also encompassed (and continues to encompass) a system of shared values and ideas from which those institutions had to draw power in order to compensate for their formal weakness.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.